Thanks to the CARES Act enacted in March, 30 million unemployed workers claimed unemployment benefits in the week ending May 16 that were more generous than they normally would have received, including nearly 11 million who would have received no benefits at all.[1] If policymakers don’t act to extend them, however, the CARES Act’s boost in benefit levels will expire on July 31 and its eligibility expansions and additional weeks of benefits will expire on December 31, while the support unemployed workers and the economy need will remain substantial.

While millions of unemployed workers have been helped by the CARES Act unemployment benefit measures, many eligible claimants have experienced difficulties in filing and delays in receiving their benefits due to the massive increase in claims since mid-March.[2] People already facing barriers to opportunity, including Black and Latino workers and those without a bachelor’s degree, were hit hardest by the massive April job losses.[3] Unemployment insurance (UI) processing delays only compound that impact.

In brief:

- The number of unemployed persons rose from an average of under 6.4 million in January and February to 21.0 million in May. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) notes, however, that as many as 4.9 million workers who were absent from work may have been misclassified as employed rather than unemployed.[4]

- The unemployment rate in May (not accounting for misclassification) was 13.3 percent. The white rate was 12.4 percent, the Black rate was 16.8 percent, and the Hispanic rate was 17.6 percent.

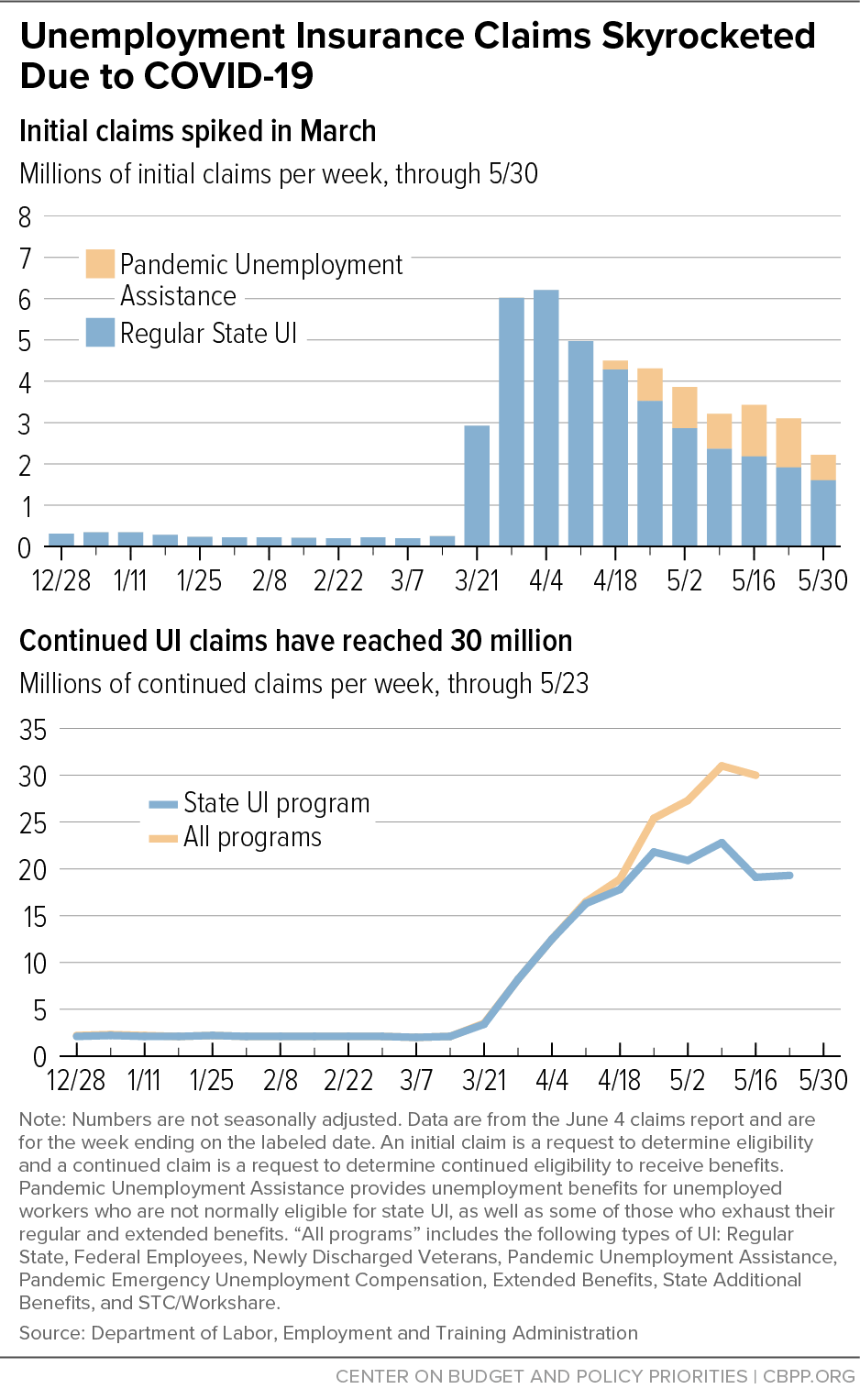

- The number of people claiming regular state unemployment insurance or other unemployment benefits rose to 30 million in the week ending May 16, from an average of 2 million in a typical week between the beginning of the year and mid-March. (See Figure 1.)

- Some 10.7 million of these workers claimed benefits through the Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) program, which provides jobless benefits to people who would not have qualified for unemployment benefits under states’ regular programs. While many states were initially slow to implement PUA, that program is now operating in all states, and in the week ending May 16, 34 states and Puerto Rico reported claimants.

- The Treasury Department reports that $48 billion of UI benefits were paid in April and $94 billion through the end of May. The majority of these payments were for the CARES Act provision that provides a $600 boost to an unemployed worker’s regular weekly benefit, whether received through the regular state UI program, PUA, or other CARES Act measures[5] — a provision that is scheduled to expire July 31.

- That expansion of eligibility and a measure providing additional weeks of federal emergency unemployment compensation to people exhausting regular state benefits are scheduled to expire on December 31. The economy is projected, however, to continue to experience very high unemployment in 2021. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that the unemployment rate will average 10.2 percent in the first quarter of 2021.

The CARES Act addressed well recognized problems with the antiquated federal-state unemployment insurance system, which is meant to help people who have lost their job through no fault of their own by temporarily replacing part of their wages. While the federal government imposes certain minimum requirements on state UI systems, states have considerable discretion over benefit levels, the number of weeks unemployed workers can get benefits, and eligibility rules, including how much prior work history workers need to qualify, whether part-time workers qualify for benefits, and whether workers who must leave their jobs for health or family reasons can get unemployment benefits.

In the low-unemployment labor market prior to the pandemic, unemployed workers ran the gamut from many who were not eligible for UI in the first place, because they did not have a long enough work history, had just entered the job market, were part-time workers and wanted to continue working part-time, had voluntarily quit their jobs to look for a better one, or had been fired to workers who were unemployed, met the UI eligibility criteria, and were either receiving unemployment benefits or had exhausted their benefits before finding a job.

State UI systems also ran the gamut from those that provided the longstanding norm of 26 weeks of benefits and had adapted their eligibility standards to 21st-century labor market conditions — which are characterized by more frequent job changes, more female workers, and more part-time work — to those that had cut the number of weeks of benefits and benefit levels after the Great Recession and had not modernized their eligibility criteria. As a result, the share of unemployed workers receiving UI prior to the pandemic ranged from a high of 57 percent in Massachusetts to lows of 11 percent in Arizona, Florida, and Louisiana; 10 percent in Nebraska, North Carolina, and South Dakota; and 9 percent in Mississippi.[6]

The CARES Act addressed the three issues of benefit levels, duration, and eligibility through the following measures:

Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (FPUC) provides an additional $600 a week on top of any other unemployment compensation for which a worker is eligible, including the other CARES Act measures, through July 31. For comparison, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 provided a $25 boost in weekly benefits in the Great Recession from February 2009 through December 2010.

Regular state benefits generally replace less than half of the average unemployed worker’s earnings.[7] Average weekly benefit amounts nationwide were $378 in March (and likely will be lower when the April data are reported, as job losers have been disproportionately people working in low-wage industries) and ranged from a high of $557 in Massachusetts to a low of $211 in Louisiana and an even lower $162 in Puerto Rico. Research suggests that a 50 percent replacement rate for 26 weeks in non-recessionary times is the lower bound for well-designed UI generosity,[8] and more is appropriate in a recession when job opportunities are scarce and lengths of joblessness — and, thus, the length of time households will have to rely on jobless benefits to pay the bills — are substantially longer. While the $600 is generous, normal levels of benefits are penurious for many workers.[9]

Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC) provides 13 weeks of federally funded benefits to people who exhaust their regular UI benefits. PEUC is the COVID version of the additional weeks of emergency unemployment compensation that the federal government has routinely provided in past recessions, although not always as quickly as PEUC was enacted.

Unemployed workers who exhaust their PEUC benefits are then eligible for state Extended Benefits (EB) if unemployment is severe enough in their state to have triggered on EB. Up to 13 or 20 weeks of EB can be available in a state, depending on its unemployment rate and UI laws. Normally, states are responsible for half the costs of EB, but the Families First Act enacted just before the CARES Act increased the federal share from 50 percent to 100 percent through the end of the year.[10]

Emergency Unemployment Compensation (EUC08) in the Great Recession and its aftermath provided a tier of additional weeks to all states regardless of their unemployment rate, as PEUC does, plus additional tiers for states with higher unemployment rates. At one point, EUC08 provided four tiers of benefits providing a maximum of 53 weeks of additional benefits for states with unemployment rates exceeding 8.5 percent.[11] That program expired at the end of 2013, when the national unemployment rate was still 6.7 percent, unemployment among Black workers was 11.9 percent, and long-term unemployment (a spell of unemployment lasting 27 weeks or longer) was still very high. PEUC is scheduled to expire at the end of this year, even though CBO projects that the unemployment rate will be 10.1 percent in the first quarter of 2021 and will still be 8.6 percent in the fourth quarter.

Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) is a new program that provides unemployment benefits to people who do not normally qualify for UI. PUA provides up to 39 weeks of benefits to: people who are not eligible for regular UI or PEUC and, in some cases, to those who have exhausted their regular state benefits and EB; people who are unemployed for a variety of COVID-related health or family reasons, like taking care of a child whose school is closed or a family member with the virus; self-employed workers and those seeking part-time work; and workers who do not have a long-enough work history to qualify for state UI benefits.

Some 10.7 million workers claimed PUA benefits in the week ending May 16. None of these workers would have qualified for any unemployment benefits in the absence of this program, making it a lifeline to millions of households. That number is likely to grow. Outdated state unemployment systems and a very large volume of applications have slowed delivery of PUA, but all states have now implemented it. As of the week ending May 16, 34 states and Puerto Rico are paying PUA claims, while the remaining states have not reported any payments yet.

Unemployment policy analysts and advocates have long sought permanent measures that would modernize the unemployment insurance system to match today’s workforce. The 2009 Recovery Act gave states incentives to expand eligibility for unemployment insurance by including more “good cause” reasons for leaving a job, allowing workers who lose a part-time job to look for another part-time job rather than requiring them to seek full-time work, and allowing a person’s most recent work history to count in the determination of eligibility and benefits rather than relying on older data that may not show adequate work history to qualify them for benefits. Some states, but not all, have adopted some or all of these measures. Restrictive eligibility criteria are one of the main reasons for the wide disparity across states in the share of unemployed workers who received unemployment insurance after the Great Recession, as described above.

Moreover, the rise in contract employment rather than traditional employer-employee relationships has sparked interest in how to protect such workers when they are out of work. PUA provides a stopgap measure during this unprecedented crisis to provide jobless benefits to unemployed independent contractors and the self-employed.

When UI was designed, the typical job loser was a married male breadwinner laid off from a full-time job to which he could expect to return when business picked up. In the 21st-century labor market, the program’s outdated eligibility requirements particularly harm women and people of color, who are more likely to fall through the cracks in UI eligibility rules. For instance, women are much likelier than men to work in part-time jobs and to leave work to care for a family member. And African American workers are much likelier than white workers to experience discrimination in job hiring and treatment on the job, leaving them more often with spotty work histories and therefore less likely to qualify for UI. (African Americans are also particularly likely to live in the South, where UI eligibility rules are generally more restrictive.)[12]

The bulk of the job losses since February were in April, and a majority of those April losses occurred in industries that pay low average wages. As a result, the deep downturn has hit hardest at workers who already faced barriers to economic opportunity, including Latino and Black workers, workers without a bachelor’s degree, and immigrants, our analysis shows.[13] Urban Institute analysis of racial disparities in receipt of UI benefits in 2010 in the depths of the Great Recession found:

…[E]ven after taking differences in education, past employment, and reasons for unemployment into account, non-Hispanic black and Hispanic workers are significantly less likely to receive UI benefits when unemployed than are their non-Hispanic white counterparts. Some of the difference may be due to workers’ choices or preferences, but some may reflect discrimination in hiring and the reported reasons for separation from those jobs, both of which can affect eligibility.[14]

The $600-per-week benefit increase and the expanded eligibility provided by PUA help reduce the disparities across state UI programs, including those arising from weak UI systems in many southern states with large Black populations. At the same time, disparities may still exist in the difficulties that different workers face in applying for UI online or by telephone and in the processing of claims.

PUA is scheduled to expire at the end of the year, yet job losses arising from the virus itself and the measures taken to control it will persist. When it is safe for workers to return to work, their former employers may have gone out of business or need fewer workers due to limited demand and social distancing requirements. Employees of businesses that are still paying them and trying to stay viable may become unemployed in coming months if those businesses ultimately are forced to close.

CBO projects that job gains will lag behind increases in economic activity, and at the end of 2021 both the demand for goods and services and employment still will be below their levels at the end of 2019.

The CARES Act provisions have helped and will continue to help many unemployed workers weather their bout of unemployment before returning to work or finding a new job. Millions of workers, however, will be in a far more precarious financial position if they lose the weekly pandemic benefit supplement and revert to what for many is a paltry regular state benefit, if they lose eligibility altogether because the PUA program expires, or if they are still unemployed and facing a tough job market going into 2021 and the extra weeks provided through the CARES Act measures are no longer available. Some workers may exhaust all currently available unemployment assistance before the end of the year or early next year. Thus, policymakers must ensure that unemployed workers are not left with little or no assistance while unemployment remains high, job prospects remain limited, and unemployment spells drag out longer than when the economy is stronger and unemployment is lower.

The table illustrates the maximum number of weeks of unemployment assistance that a worker in a state with 26 weeks of regular UI, a worker in a state that provides fewer than 26 weeks of regular UI (using the 12 weeks provided by Florida and North Carolina as the example[15]), and a person who is not eligible for regular state UI but is eligible for PUA, respectively, can receive as long as enough weeks are left in the year to receive the full number of CARES Act weeks.

| TABLE 1 |

|---|

| |

Maximum Number of Weeks of Regular UI Available |

|---|

| Program |

26 weeks |

12 weeks |

Ineligible for Regular UI |

| Regular UI |

26 |

12 |

0 |

| PEUC |

13 |

13 |

0 |

| EB |

13 |

6 |

0 |

| PUA |

0 |

21 |

39 |

| Total |

52 |

52 |

39 |

A worker who exhausts regular state benefits first becomes eligible for PEUC, then EB (if available). Weeks of regular UI and EB count against the 39 weeks of PUA. Hence, a person who has received 26 weeks of regular UI and 13 weeks of EB is not eligible for PUA. A person in a state with a maximum of 12 weeks of regular UI who has exhausted them and 6 weeks of EB is eligible for up to 21 weeks of PUA before it expires at the end of the year; a person eligible only for PUA can receive up to 39 weeks before it expires at the end of the year.

Without new legislation, unemployed workers no longer will be able to claim PEUC or PUA after December 31, even if they have weeks still available, but they can continue to claim any regular state UI or EB to which they are entitled. States began triggering on to EB in April and benefits first became payable the week beginning April 26. By the week beginning May 31, EB was payable in 44 states.

In the week ending May 23, 16.7 million (86 percent) of the 19.3 million people receiving regular state UI were in the 39 states that provided 26 weeks of regular benefits and 13 (or 20[16]) weeks of EB. Of these, workers who received their first UI payment between the week ending January 4 and the week ending April 4 can receive up to 52 weeks of coverage, since they already will have moved through PEUC and into EB by year-end. Those who started regular UI in the first week of 2020 will exhaust their 13th week of EB in the last week, and many of the rest may have only a few weeks of EB left in 2021.

PUA is available for weeks of unemployment beginning on or after January 27 through weeks ending on or before December 31 and people whose first PUA payment was before the week ending April 4 will exhaust their 39 weeks of PUA before the end of the year. Similarly, people eligible for regular UI whose unemployment spells began in the second half of 2019, when unemployment was low and job opportunities were generally plentiful, but now remain unemployed in the wake of the pandemic will exhaust all available unemployment assistance before the end of the year. Many unemployed workers in states offering fewer than 26 weeks of regular UI, and hence also fewer weeks of EB, will lose any remaining PUA benefits if PUA expires at the end of the year.

The House Heroes Act would extend the CARES Act UI measures to January 31, 2021 and would allow people in the midst of a PEUC or PUA spell on that date to continue any remaining weeks up to March 31, 2021. That proposal would extend availability of assistance to some but not all of the people who would otherwise be cut off from these programs at the end of 2020. But unemployment will still be very high and jobs scarce in April 2021.

The unemployment rate in May was 13.3 percent and 20.1 million fewer people had jobs than in February. The white rate was 12.4 percent, the Black rate was 16.8 percent, and the Hispanic rate was 17.6 percent. White employment was down 12.7 percent from February, while Black employment was down 16.3 percent and Hispanic employment was down 19.5 percent.

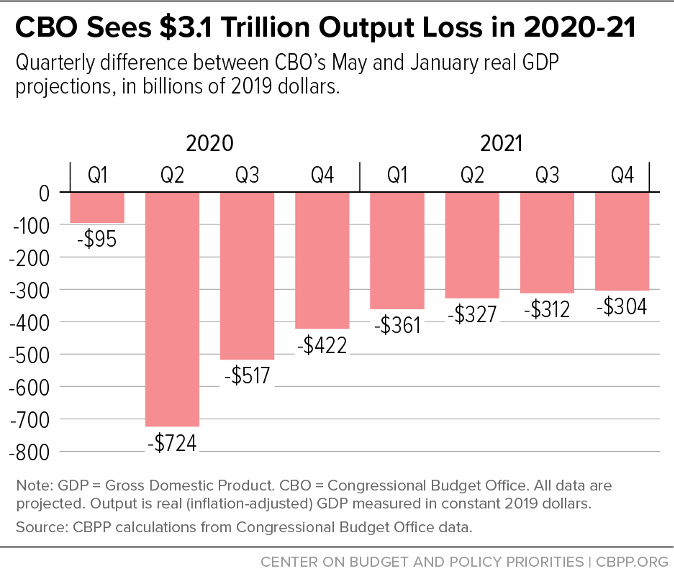

A broad consensus among economic forecasters sees the economy operating with high unemployment through 2021. CBO describes its latest economic projections, which assume that current laws generally remain unchanged, i.e., that policymakers do not enact any further stimulus or assistance, as producing a “gradual and incomplete recovery” thorough 2021 and beyond. In particular, CBO projects that in 2020-2021, real GDP (economic output measured in constant 2019 dollars) will be $3.1 trillion less than it projected in its January Budget and Economic Outlook.[17] (See Figure 2.)

Forecasters, including CBO, expect the depth of the economic contraction and height of unemployment to occur in the current April-May-June quarter by amounts unprecedented since the 1930s. They then see the economy turning around in the second half of the year, in part due to the assistance and stimulus that already has been provided. In fact, the growth in GDP and employment is projected to be stunningly large in the second half of the year. But that’s because of how deep a hole the economy will be starting from.

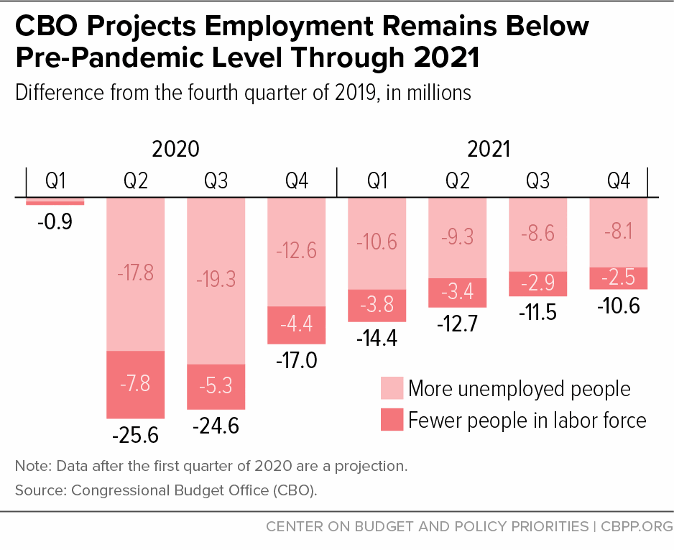

While growth may be rapid, millions of people will remain out of work and GDP will remain well below pre-crisis levels. In CBO’s projections of the fourth quarter of 2021, the levels of GDP and employment will still be far below where they were in the fourth quarter of 2019 and at levels that would be considered recessionary in normal times. GDP will still be 1.6 percent below its level in the fourth quarter of 2019. The unemployment rate, at 8.6 percent, will be closer to its 10 percent Great-Recession-era high of a decade ago than to what it would be in a healthy economy, and 8.1 million fewer people will have jobs and the labor force will still be 2.5 million people smaller than at the end of 2019, due to people dropping out and no longer actively looking for work. (See Figure 3.)

While the economy may be starting to recover from the depths of the recession in the second half of this year, jobs and employers that existed when the layoffs began may no longer exist. Employers that have tried to hang on may go out of business even though the economy is recovering, leaving their employees without a job. Or it may not be safe to go back to work even as social distancing restraints are being relaxed. And without additional federal fiscal relief, massive state and local government job losses (1.6 million since February) will worsen as balanced budget requirements force state governments to slash their budgets.[18]

As explained above, millions of workers who are still unemployed and receiving unemployment insurance will see a sharp drop in their weekly income if the $600 emergency pandemic compensation ends on July 31. Even before the end of the year, some people will run through all available unemployment assistance while the unemployment rate still is very high. Finally, expiration of the PUA program, which enacts on a temporary basis measures to expand eligibility like those that have been integral to UI reform efforts over the years, will leave millions of unemployed workers with nothing.

Notwithstanding the preciseness of its projections, CBO, like all responsible forecasters, acknowledges the inherent uncertainty. In the current situation, CBO acknowledges that its interim forecast depends heavily on social distancing assumptions, saying, “The range of uncertainty about social distancing, as well as its effects on economic activity and implications for the economic recovery over the next two years, is especially large.”

The economic stimulus policymakers provided in the Great Recession was substantial and effective at keeping the Great Recession from being even worse, but an even bigger package was needed at the outset, given the depth of the hole the economy had fallen into. Moreover, policymakers turned away from stimulus prematurely, leading to a more protracted recovery.[19]

In the current crisis, policymakers have taken bold action and enacted substantial stimulus, but they should beware repeating the experience during the recovery from the Great Recession. The best way to do that is to have measures whose duration is tied to the state of the labor market rather than to arbitrary calendar dates.[20] That way, measures stay in place as long as they are needed, but no longer.

Policymakers missed a chance when the economy got on solid footing in the later stages of the long expansion from the Great Recession to make UI reforms that would modernize benefit levels and eligibility standards and strengthen the program’s “automatic stabilizer” properties so that when a recession hit, a larger share of unemployed workers would receive benefits quickly, the benefits would replace a larger share of workers’ lost earnings, and the duration of benefits would depend on the duration of the recession, without requiring new legislation.

Policymakers, of course, would always retain the option of turning measures on or off sooner, but the default would be that they would be tied to conditions in the national or individual state economy. Ideally extensions of or replacements for CARES Act unemployment insurance measures would provide a model for permanent UI reform to help both unemployed workers and the economy in future recessions as well.