- Home

- Discretionary Caps In Gregg Bill Would L...

Discretionary Caps in Gregg Bill Would Lead To Overly Deep Cuts

Proposed Caps Could Actually Hinder Enactment of Large-Scale Deficit Reduction

Senate Budget Committee Chairman Judd Gregg (R-NH) has introduced legislation (S. 3521) that would make a number of far-reaching changes in the federal budget process. The Senate Budget Committee is scheduled to mark up that legislation on June 20.

Included in the legislation are provisions that would establish statutory caps for each of the next three years on overall levels of funding for discretionary programs (i.e., programs that are non-entitlements). Under the proposal, the caps for fiscal years 2007, 2008, and 2009 would be set at the overall level for discretionary programs proposed for each of those years in the budget that the President submitted to Congress in February.

These caps are designed to lock in the overall discretionary funding and expenditure levels in the Bush budget and likely would lead to substantial cuts in domestic discretionary programs. The Bush budget contains cuts over the next three years in every domestic discretionary program area in the federal budget except for science, space, and technology.

Moreover, the Gregg bill would set a statutory cap for fiscal year 2007 that is more than $7 billion belowthe level that would be established under the budget resolution the Senate approved on March 16. The Gregg bill would enforce these caps by triggering automatic across-the-board cuts in discretionary programs if the caps would otherwise be exceeded.

Proposed Caps Would Require Deep Cuts in Domestic Discretionary Programs

Chairman Gregg’s proposal to set discretionary caps for each of the next three years at the level of funding proposed by the President would necessitate steep cuts in domestic discretionary programs over the three years, unless defense and international programs are funded at levels well below those the President has requested.

-

Under the President’s budget, overall funding for domestic discretionary programs (programs other than those related to defense or international affairs) would be reduced by $66 billion over the next three years. This is the amount by which these programs would have to be cut under the proposed caps, unless defense and international affairs programs were funded at levels below those reflected in the budget. (The $66 billion figure represents the amount by which the funding levels in the President’s budget fall below the CBO baseline, which is CBO’s estimate of the amounts needed to maintain current levels of service in these programs and equals the fiscal year 2006 funding levels for these programs, adjusted only for inflation. The funding levels the President has proposed fall somewhat further — $80 billion — below the OMB baseline levels. The difference reflects the fact that OMB assumes somewhat higher levels of inflation then CBO does.[1])

-

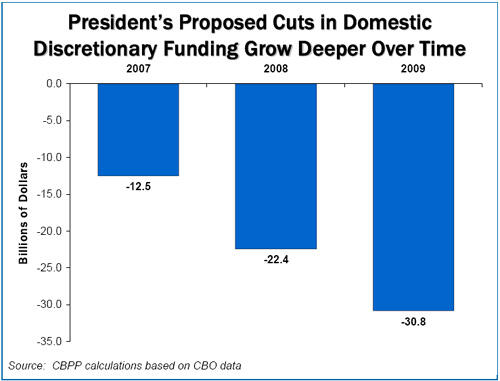

Under the President’s budget, the reductions in domestic discretionary programs would grow larger with each passing year, reaching $31 billion a year in 2009, the last year for which a cap is proposed in Chairman Gregg’s legislation.[2] (See chart above.) By that year, expenditures for domestic discretionary programs would fall to their lowest level, measured as a share of the economy, since 1964.

Proposed Caps Depart from the Successful Experience in the 1990s

The cuts that the proposed caps would necessitate depart sharply in two respects from the experience with discretionary caps in the 1990s, when such caps proved effective. First, the caps in effect through most of the 1990s were part of larger, carefully balanced deficit-reduction packages. Both in 1990 when discretionary caps were first established and in 1993 when they were extended, discretionary caps were instituted as part of broad deficit-reduction legislation that combined restraint on discretionary programs with increases in taxes (particularly for those who could best afford to pay more) and specific reductions in entitlement programs (in part by reducing Medicare payments to health-care providers). The discretionary caps of the 1990s also were accompanied by “Pay-As-You-Go” rules that required both entitlement expansions and tax cuts to be offset fully. In short, the discretionary spending caps of the 1990s were part of a larger program of shared sacrifice that was spread acrossthe population and that played a major role in addressing the large deficits of that era.

Chairman Gregg’s new cap proposal is different. It is not part of a balanced plan of deficit reduction in which legislation is enacted that increases revenues and achieves specific savings in entitlement programs. Instead the cap proposal is part of a plan that promises future unspecified cuts in entitlement and discretionary spending (to be achieved through automatic across-the-board cuts and/or fast-track consideration of legislation proposed by Republican-dominated commissions if Congress continues to avoid making the difficult specific cuts in programs) while not only exempting taxes from the automatic budget mechanisms but allowing continued, deficit-financed tax cuts that would not be subject to any fiscal discipline.

The Gregg discretionary caps would depart sharply from the caps enacted in 1990 and 1993 in another respect as well. The cuts in domestic discretionary programs that would be required under Senator Gregg’s proposed caps (unless Congress funded defense and international programs at levels below those the President has requested) would be nearly six times as deep (measured as a share of the economy) as the domestic discretionary program cuts instituted under the discretionary caps enacted in 1990 and 1993.

Why the Proposed Caps Are Ill-Advised

This analysis finds Chairman Gregg’s proposal to cap funding for discretionary programs at the levels proposed in the President’s budget for the next three years to be ill-advised. The caps would be inequitable. They also would be likely to do more to hinder fiscal discipline than to advance it. The proposed discretionary caps have at least five basic flaws.

-

The cuts they would require are too severe. As noted, the President’s budget calls for funding cuts in domestic discretionary programs that total $66 billion over three years and reach $31 billion in 2009. Funding for 14 of the 15 domestic discretionary program areas (or budget functions) would be cut over the next three years; every area except science, space, and technology would be hit. Among the domestic program categories that would sustain hefty cuts are education, environmental protection, national parks, medical research, veterans health care, and housing and homeless programs, among numerous others.

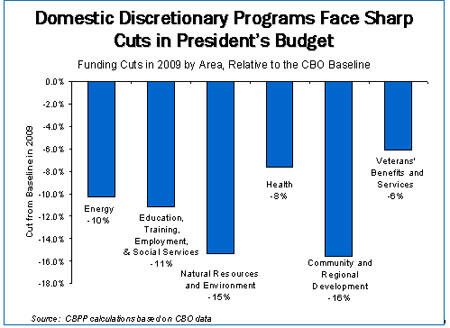

For example, the President’s budget envisions cuts in environmental and natural resource programs of 15 percent by 2009. (In other words, funding for these programs in 2009 would fall 15 percent — or $5 billion — below the CBO baseline, which equals the 2006 funding level adjusted for inflation.) Even veterans programs that are not entitlements (principally veterans’ health care) would be cut 6 percent, or almost $2 billion, in 2009. The table below shows, for selected discretionary programs, the cuts in 2009 funding proposed in the President’s budget. -

These cuts are not part of a balanced package. As noted, the discretionary spending restraints enacted in the early 1990s were part of broader deficit-reduction efforts that entailed shared sacrifice. Members of Congress who favored increased discretionary spending, Members who sought entitlement expansions, and Members who wanted tax cuts all agreed to forgo their favored proposals in return for restraint on all parts of the budget.

The new discretionary cap proposal is offered in a different context. Not only are there no increases assumed on the revenue side of the budget, but the Gregg proposal would allow all of the recent tax cuts to be extended and made permanent and other new tax cuts to be enacted. (Over the next ten years, the cost of the extending the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts — a policy reflected in the President’s budget — would total $3.3 trillion, including the costs of extending Alternative Minimum tax relief and the costs of the added interest payments on the debt.) -

The proposed discretionary caps would likely make it harder to secure agreement in coming years on a major deficit-reduction package. One lesson of the 1990s is that passing large-scale deficit-reduction measures entails putting all parts of the budget on the table and having various Congressional factions agree to accept deficit-reduction measures affecting their favored parts of the budget in return for the application of such measures to the other parts of the budget as well. To craft large-scale deficit reduction measures that can pass and be sustained, discretionary programs, entitlement programs, and taxes all need to contribute.

Yet the proposed three-year discretionary caps are so austere with regard to domestic programs that further cuts in discretionary spending over the next three years would almost certainly be out of the question. That would make it considerably more difficult to craft a major deficit-reduction package after the 2006 election, since there would be nothing left to give on the domestic discretionary side of the budget to help induce those who favor continued tax cuts to agree to start restoring the federal revenue base.

The proposed three-year discretionary caps consequently are likely to set back the cause of deficit reduction, which badly needs a large, multi-year deficit reduction package that covers all parts of the budget. For reasons of both equity and fiscal responsibility, the proposed caps consequently appear worse than no caps at all. -

History shows that unrealistically severe discretionary caps get blown away and may weaken fiscal discipline. In 1990 and 1993, discretionary caps that placed realistic restraints on discretionary programs were enacted. Those caps were honored.[3] In 1997, far more austere caps were established as part of the 1997 Balanced Budget Act, which sought to produce a balanced budget by 2002 under the budget assumptions in use at that time. These caps were so tight that Congress could not live with them, and they were blown away. The ultimate result was no meaningful restraint at all on discretionary spending. (See the table on the following page.)

The lesson is that reasonable caps negotiated as part of a balanced deficit-reduction package that contains shared sacrifice can be effective, but caps that are too severe are not sustained, especially when they are not part of a larger, balanced set of deficit-reduction policies. (Another factor that weakened Congress’ ability to adhere to the austere caps set in 1997 — which would have required substantial reductions in discretionary programs — was that Congress simultaneously began passing tax cuts that were not offset and that violated the “Pay-As-You-Go” rules, then part of federal law. If fiscal discipline is not enforced in other parts of the budget, it is difficult to enforce rules that require cuts in discretionary programs.)

he caps that Chairman Gregg is proposing would entail reductions in domestic discretionary programs at least as deep as those called for under the unrealistic caps that were enacted in 1997 and could not be sustained.[4]

| Cuts in Fiscal Year 2009 Funding for Selected Domestic Discretionary Programs Proposed by President Bush in His Fiscal Year 2007 Budget | ||

| Program | Cut (in millions of dollars) | Cut (as a percent) |

|

|

|

|

| Women, infants, and children nutrition (WIC) | -$459 | -8.4% |

| Vocational and adult education | -$1,544 | -73.5% |

| Children and families services (including Head Start) | -$1,401 | -15.0% |

| National Institutes of Health | -$2,504 | -8.3% |

| Low-Income Home Energy Assistance (LIHEAP) | -$1,622 | -48.6% |

| Community Oriented Policing Services (COPS) | -$299 | -75.3% |

| Energy conservation | -$191 | -23.1% |

| Community development fund | -$1,836 | -41.7% |

| EPA Clean Water and Drinking Water | -$354 | -19.4% |

| Cuts represent reductions in funding below the Congressional Budget Office’s baseline projection for 2009, which is the level of funding enacted for the program in 2006, adjusted for inflation. For the LIHEAP program, We adjusted CBO’s baseline projections to take into account $1 billion originally provided as mandatory funding for 2007, which was subsequently made available in 2006. The cut in 2009 would be $567 million if that funding were not reflected in the baseline projection. | ||

| The Discretionary Caps Agreed to in 1990 and 1993 Were Adhered to, the More Severe Caps Passed in 1997 Were Not, and the Proposed Caps Are Even More Severe | |||

| Change in expenditures for domestic discretionary programs | Actual Change from 1990 through 1998 (actual results, which were consistent with caps) | Assumed change from 1998 through 2002 under caps enacted in 1997 a | Proposed change from 2006 to 2009 under President’s budget plan |

| As a share of GDP | -0.1% of GDP | -0.6% of GDP | -0.6% of GDP |

| Average annual growth rate of domestic discretionary spending, adjusted for inflation and population | +0.5% per year | -2.7% per year | -4.6% per year |

| a. Assumes the subdivisions between defense, international, and domestic programs set forth in the 1997 budget agreement. Under that agreement, defense and domestic programs were assumed to be squeezed equally hard, although that was not required as a matter of statute. In practice, funding for all types of discretionary programs — defense, international, and domestic — exceeded the caps set in the 1997 agreement by increasingly large amounts starting in fiscal year 1999. | |||

Conclusion

Enactment of the proposed three-year caps on discretionary programs at this time would be both inequitable and unwise. The proposal by Chairman Gregg to cap discretionary spending at the levels proposed by President Bush is designed to lock in substantial reductions in a very broad array of domestic discretionary programs. These cuts would not be part of a comprehensive, balanced approach to deficit reduction, as the multi-year caps established in the early 1990s were.

In addition, the establishment of discretionary caps at the President’s proposed levels of spending at this time would likely make it harder in the next few years to craft a large bipartisan deficit-reduction measure that seeks shared sacrifice from all parts of the budget. Advocates of cuts in domestic discretionary programs would already have achieved their goal, making it harder to induce them to support cuts in defense or increases in revenues in return for constraints on domestic programs. Conversely, advocates of domestic discretionary programs would be unlikely to support any deal that calls for even deeper cuts in those programs.

Adoption of the proposed caps thus would be ill-advised. Both from the standpoint of fiscal responsibility and from the standpoint of advancing the well-being of the American public in areas ranging from the environment to education to health and safety to aiding the less fortunate, the proposed caps would be likely to do more harm than good.

End Notes

[1] This analysis uses a CBO baseline that has does not assume that the same level of emergency discretionary funding enacted for 2006 (for the war in Iraq and Afghanistan, hurricane relief, and for other purposes) will be provided for 2007 and each succeeding year. For comparability, emergency funding proposed by the President for 2007 is also excluded from the analysis.

[2] The President’s budget proposed that caps also be established for 2010 and 2011, with the assumed cuts in domestic discretionary funding under those caps growing to $47 billion in 2011.

[3] The caps allowed emergency expenditures under circumscribed conditions. Through 1998, emergency funding was used only for the Gulf War and major natural disasters.

[4] It also may be noted that the Senate voted during its recent consideration of the budget resolution for 2007 to increase total funding for discretionary programs in 2007 to a level more than $7 billion above the President’s proposed cap level for that year (not counting emergency funding proposed in the Senate budget plan or the President’s budgets). Taking into account the effects of an amendment by Senator Specter (R-PA) dealing with advance appropriations that the Senate adopted, the budget resolution passed by the Senate made room for more than $14 billion more in domestic discretionary funding for fiscal year 2007 than the amount that the President proposed.