Some proponents of converting Medicaid to a block grant have attributed the success of the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) in extending coverage to millions of low-income uninsured children to the program’s financing structure, which provides states with fixed allotments rather than open-ended federal financing.[1] They argue that states could fare similarly well under a Medicaid block grant. In reality, however, Medicaid under a block grant would operate very differently than CHIP.

Congress has taken extraordinary steps over a number of years to ensure that states always had adequate federal funding to sustain (and expand) their CHIP programs, thereby allowing states to overcome CHIP’s flawed capped funding structure. In contrast, Medicaid block grant proposals, like the one proposed under the budget plan that the House approved in April, are explicitly designed to reduce federal funding well below currently scheduled levels in order to generate large budgetary savings. These deep reductions would force states to slash Medicaid eligibility, cap enrollment, reduce benefits, or further cut provider reimbursement rates.[2]

Thanks to Medicaid and CHIP, the number and percentage of children without health insurance have declined significantly over the last decade, despite the steady erosion of employer-sponsored insurance, two recessions, and the resulting increase in the overall ranks of the uninsured. For example, during the most recent recession, Medicaid and CHIP were instrumental in preventing children from becoming uninsured, even as families lost their jobs and employer-sponsored coverage. In 2009, the proportion of children covered by Medicaid and CHIP grew by 3.5 percentage points to offset a 3.1 percentage point decline in employer coverage for children.[3]

But CHIP’s capped financing structure, far from making these successes possible, placed the program at risk of failure. In CHIP’s early years, some states received much more funding than they needed, while other states received much less than they needed. In addition, state allotments often fluctuated significantly from year to year.

CHIP has overcome these serious shortcomings because it differs substantially from a typical block grant:

- Aggregate federal funding for state CHIP programs was set at levels that were more than adequate to meet states’ financing needs during CHIP’s first ten years. States received roughly $40 billion in CHIP allotments from 1998 through 2007 and spent slightly less than $35 billion. The House budget plan’s Medicaid block grant, in contrast, would give states significantly less federal funding than they need to sustain their current programs. CBO estimates that federal Medicaid funding under the House budget plan would be reduced by 35 percent in 2022 and by 49 percent in 2030, relative to current law. (These percentage reductions do not include the additional reductions in federal Medicaid spending that would result from the House budget plan’s repeal of the Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act.)

- In CHIP, federal funding not used by the state to which it was originally allocated is redistributed to other states. Even if the Medicaid block grant envisioned under the House budget plan were designed to allow for the redistribution of unspent funds, there would be little or no unspent funds to redistribute because of the deep federal Medicaid funding cuts to which all states would be subject (relative to the funding they would receive under current law).

- Furthermore, whenever redistributed CHIP funds have not been sufficient to close states’ federal CHIP funding gaps, Congress has stepped in to provide additional CHIP funding. As a result, states have effectively been able to operate the CHIP program as though they had uncapped federal funding: The combination of states’ annual allotments, redistributed funds, and supplemental funding from Congress has given states all of the federal CHIP funding they have needed.[4]

- When Congress reauthorized CHIP for five years in 2009 (and further through 2015 as part of the Affordable Care Act), it set federal funding high enough to ensure that all states have sufficient CHIP funding to not only sustain their current programs but to significantly expand them to enroll more uninsured children. CBO has estimated that no state will see federal funding shortfalls in the years ahead and that states collectively will be able to cover 4 million more uninsured children.

In short, due to CHIP’s significant initial funding and repeated congressional efforts to ensure adequate funding for state programs, CHIP has effectively operated like a program without a binding federal funding cap. The situation would be very different under a Medicaid block grant like that envisioned under the House budget plan, where states almost certainly would have no choice but to institute deep Medicaid cuts because of the magnitude of the federal funding reductions. The Urban Institute has estimated that under the House plan’s block grant, states would have to reduce Medicaid enrollment by between 14 million and 19 million people by 2021 — assuming across-the-board enrollment cuts to all beneficiary groups — relative to the current program (and before counting the additional loss in enrollment under the House budget plan from repeal of the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion).[5]

As part of the Balanced Budget Act of 1997, Congress established CHIP and appropriated $40 billion in funding for the program’s first ten years (1998-2007). Analysis at the time projected that this amount would be more than adequate to meet CHIP’s goal of covering uninsured low-income children in families with incomes too high to receive Medicaid.[6] That proved to be the case, as states spent a total of roughly $35 billion over that ten-year period, while covering about 4.5 million children in 2007.[7]

In contrast, the House budget plan’s Medicaid block grant is explicitly designed to provide significantly less federal funding than states would need to sustain their current Medicaid programs. The House budget would cut federal Medicaid spending by $771 billion over the next ten years (outside of repealing the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion), with the block grant achieving $750 billion of those savings. [8] As a result, under the House budget plan, federal Medicaid funding would be 35 percent lower by 2022 and 49 percent lower by 2030, relative to current law, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

Unlike Medicaid, under which the federal government picks up a fixed percentage of states’ costs, CHIP provides states with a fixed allotment of federal funding that may or may not correspond to their actual financing needs. [9] During CHIP’s original ten-year authorization (1998-2007), the formula used to distribute CHIP funding among states proved to be a poor measure of actual need, in part because it used retrospective data and did not account for variations in state efforts to enroll eligible children.[10]

For example, a state’s 2006 CHIP allotment was based on data on the number of low-income and uninsured children in the state from 2001 through 2003. A state that experienced significant demographic change or implemented a major expansion or outreach effort after 2003 did not receive a corresponding increase in its 2006 allotment. Between 2005 and 2006, for example, Arkansas’s CHIP enrollment increased by more than 8 percent but its federal allotment decreased by 10 percent. Arkansas eventually faced a federal CHIP funding shortfall in 2008 because of this mismatch between its allotments and its spending.[11]

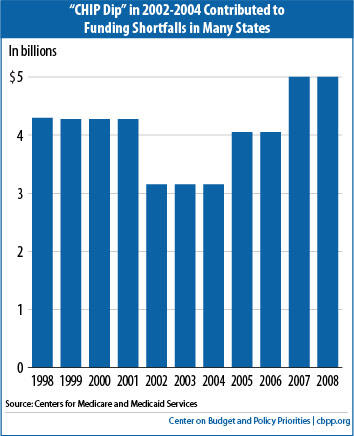

Moreover, CHIP’s annual funding levels were not aligned with the program’s expected growth and spending needs over time. When Congress enacted CHIP, it set annual allotment levels for the first ten years based on overall deficit reduction targets in the Balanced Budget Act of 1997. CHIP was essentially funded over the first four years as if it were fully implemented, even though states were just establishing their programs and ramping up enrollment and thus did not need all of the federal funds provided. Then, under the so-called “CHIP Dip,” federal funding declined by $1 billion (27 percent) from the 2001 level in 2002, 2003 and 2004, just as state programs were maturing (see Figure 1). Together with the allocation formula, the CHIP Dip left a number of states without sufficient federal funding to sustain their CHIP programs just when they had ramped them up.

Fortunately, the excess federal funding in CHIP’s early years created a large pool of unspent funds for states facing inadequate federal funding. States were given a limited period of time (initially three years) in which to spend their annual allotments; any unspent funds were then redistributed to other states. While both the Administration and Congress made policy changes regarding the redistribution of funds (see the appendix), in general, unspent funds were redistributed to help ensure that no state faced a federal funding shortfall when its needs exceeded the amount of federal funding available. Notably, both Mississippi and Wisconsin — whose current governors have attributed CHIP’s success to its capped federal funding — were among the states whose capped allotments proved insufficient and which relied on unspent funds redistributed from other states prior to 2009.[12]

Substantial amounts of unspent funds available for redistribution to other states would be extremely unlikely to materialize under the Medicaid block grant that the House budget calls for, even if the block grant allowed such redistribution of funds — few, if any, funds would remain unspent and available for redistribution because of the deep funding cuts that all states would face.[13]

Table 2:

States with Insufficient Federal CHIP Funding

by Year

(Available CHIP Funds as a % of Need After Any Redistributed Funds but Before Special Appropriations) |

| State | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 |

| Alaska | | | 81% |

| Arkansas | | | 92% |

| California | | | 86% |

| Georgia | | 67% | 75% |

| Illinois | 84% | 60% | 71% |

| Iowa | 99% | 81% | 60% |

| Louisiana | | | 76% |

| Maine | | 79% | 47% |

| Maryland | 93% | 71% | 48% |

| Massachusetts | 86% | 64% | 46% |

| Minnesota | | 98% | 68% |

| Mississippi | 64% | 90% | 43% |

| Nebraska | 81% | | 61% |

| New Jersey | 80% | 66% | 46% |

| North Carolina | | | 78% |

| North Dakota | | | 72% |

| Ohio | | | 97% |

| Rhode Island | 75% | 99% | 46% |

| Source: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services |

As states fully implemented their CHIP programs over the past decade, the CHIP financing system began to fail. The flaws in the allocation formula for states, as well as the CHIP Dip’s reduction in annual federal funding, meant that more states were fully spending their federal funds and that a growing number of states had insufficient federal funding to sustain their CHIP programs. As a result, fewer unspent CHIP funds were available for redistribution. By 2006, states were facing federal funding shortfalls that could not be closed with redistributed funds.

In that year, Congress appropriated $283 million in additional CHIP funding to close expected federal CHIP funding shortfalls in 12 states.[14] This represented more than 5 percent of federal CHIP spending in that year. In 2007, Congress authorized the Secretary of HHS to provide an additional $528 million — or 9 percent of total federal CHIP spending — to states facing federal funding shortfalls. Likewise, in an interim one-year extension of CHIP in 2008, Congress provided an additional $1.6 billion in federal CHIP funding, about $1 billion of which went to 19 states expected to face federal funding shortfalls. The additional appropriation represented more than 14 percent of federal CHIP spending in 2008. Mississippi received funds under each of these supplemental CHIP appropriations to avert federal funding shortfalls.

In essence, Congress repeatedly stepped in to ensure that states could operate their CHIP programs as if they faced no federal funding cap. States received all of the federal CHIP funding they needed each year. Under a Medicaid block grant like the one in the House budget plan, by contrast, states would receive a fixed annual amount of federal funding, set at levels well below what they need for their current programs. States could not count on any additional federal funding being provided.

When Congress reauthorized CHIP in 2009, it ensured that no state would face federal funding shortfalls through the five-year reauthorization period (2009-2013). It set generous national allotment levels each year and redesigned the allocation formula that determined individual states’ allotments by tying CHIP funding levels more closely to what states were actually spending. It also continued the practice of redistributing any unspent funds to states that face federal funding shortfalls. As a result, CBO projected that no state would face a federal CHIP funding shortfall, and that 4 million more uninsured children would be covered by CHIP or Medicaid by 2013.

While some states have placed caps on enrollment in their CHIP programs, this was not due to capped federal allotments; instead, state budget problems stemming from economic downturns have led some states not to provide the full share of state funds needed to maintain their CHIP programs. In response to the pronounced economic downturn in 2001, seven states froze CHIP enrollment (Alabama, Colorado, Florida, Maryland, Montana, North Carolina, and Utah). Although federal CHIP funding was adequate, these states determined they could not adequately finance the state share of CHIP costs — which accounts, on average, for 30 percent of the total cost. Tens of thousands of uninsured, low-income children eligible for their states’ CHIP programs were prevented from enrolling in coverage as a result. For example, enrollment in North Carolina’s Health Care Choice program declined by 20,000 children, or 30 percent, between January and October of 2001.

These states were not able to close their funding shortfalls merely by eliminating inefficiencies, as some proponents of block-granting Medicaid and cutting its funding have argued could be done to offset the federal Medicaid funding reductions that would be made. Rather, states with inadequate state CHIP funding were forced to freeze CHIP enrollment and leave eligible low-income children uninsured. In fact, the losses in children’s coverage resulting from these enrollment freezes were one key reason why Congress took various steps to ensure that no states faced federal funding shortfalls that could result in enrollment caps or reductions in CHIP eligibility levels.

As part of the Affordable Care Act, Congress extended CHIP funding through 2015. The latest CBO baseline for CHIP indicates that states have more than enough federal funding to both sustain their current programs and enroll more uninsured low-income children. This means that through 2015, states can continue to operate their CHIP programs as if no federal funding cap existed.

Unlike in the case of CHIP, most proposals to block grant Medicaid have been explicitly designed to reduce federal funding well below what it would be under current law. This would leave states “holding the bag”: they would either have to make up the difference by providing additional state funding or institute cuts to eligibility, benefits, and/or provider rates to compensate for the loss of federal funding.

Should the federal government reduce its financial commitment to Medicaid, both states and low-income beneficiaries would be adversely affected. Federal Medicaid dollars represent the largest fund transfer from the federal government to the states. On average, federal Medicaid funds represent 14.4 percent of states’ total spending, a much larger share than federal CHIP funds.[15] Filling budget gaps created by capped federal Medicaid financing would prove very difficult for states.

Capping federal Medicaid funding would also threaten the program’s fundamental role as the care provider for the nation’s most vulnerable populations. [16] Medicaid serves a significantly larger population than CHIP — 50 million people, as opposed to CHIP’s 5 million. [17] Also, Medicaid serves a significantly broader population than CHIP, providing health care not only to poor children but also to parents, seniors, and people with disabilities, including people in nursing homes. Seniors and people with disabilities have more significant health care needs than other groups, and the cost of their care varies more in response to procedural and technological advances. The cost of serving an elderly person or a person with a disability in Medicaid is four to six times that of serving a child.[18]

In serving low-income families, Medicaid also takes on added importance during economic downturns. Medicaid enrollment among families grew 34 percent during the economic downturn of the early 2000s and its aftermath. Similarly, Medicaid enrollment among families has grown 25 percent since June 2007, following two years of enrollment decline.[19] In both instances, increases in federal Medicaid financing were necessary to enable Medicaid to play its role of preventing an economic downturn from expanding the ranks of the uninsured to a greater degree.

The Urban Institute has estimated that, under the House block grant, states would reduce Medicaid enrollment by roughly 14 million to 19 million — assuming across-the-board cuts to all beneficiary groups — relative to the current program (excluding the Affordable Care Act’s Medicaid expansion). The Urban Institute also estimated that the resulting enrollment cuts (and reimbursement cuts) would effectively result in a 31 percent average reduction in the overall payments made to providers, including hospitals, physicians, and nursing homes. If states attempted to fill in for the lost federal Medicaid funds to avoid enrollment losses, state contributions to the cost of Medicaid would have to increase by 45 percent to 71 percent.[20]

A fundamental feature of proposals to cap Medicaid funding is a reduction in federal funding well below the levels required to meet current service needs. Medicaid under a block grant would operate very differently than CHIP, a program for which Congress has always ended up providing states with adequate funding to sustain (and expand) their CHIP programs. Facing sharply reduced federal Medicaid funding, states would have to cut eligibility, cap enrollment, reduce benefits, and/or further cut provider reimbursement rates, with adverse impacts on low-income beneficiaries.

The following CHIP legislation modified aspects of the program’s financing:

Balanced Budget Act (BBA, P.L. 105-33)

The BBA enacted the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) and set annual allotment levels for the initial ten-year authorization period. A formula was established for distributing the national allotment among states. The HHS Secretary was given authority to redistribute unspent annual SCHIP funds after three years to states that had spent their allotments

Benefits Improvement and Protection Act (BIPA, P.L. 106-554)

Enacted in December 2000, BIPA established the method for redistributing states’ unspent 1998 and 1999 SCHIP allotments. The somewhat complicated formula led to sizable redistributions to a small number of states through 2002.

SCHIP Program Allotments Extension (P.L. 108-74)

Enacted in August 2003, the legislation: (1) extended the availability of $1.4 billion in unspent SCHIP funds that otherwise would have expired and reverted to the Treasury; (2) established a method for redistributing unspent 2000 and 2001 SCHIP funds; and (3) permitted “early-expansion states” to use a portion of their SCHIP funds for 1998 through 2001 for Medicaid eligibility expansions for children instituted prior to SCHIP.

Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 (DRA, P.L. 109-171)

Enacted in February 2006, the DRA provided a $283 million supplemental appropriation for CHIP to prevent shortfalls projected in 12 states. It also extended the Medicaid refinancing provision for “early-expansion states” to apply to these states’ 2004 and 2005 CHIP allotments.

NIH Reauthorization Law (NIH, P.L. 109-482)

Enacted in January 2007, the legislation: (1) directed all redistributed 2004 SCHIP funds to states projecting shortfalls; (2) expedited redistribution of 2005 SCHIP funds to states projecting shortfalls; and (3) extended the Medicaid refinancing provision for “early-expansion states” to states’ 2006 and 2007 SCHIP allotments.

US Troop Readiness, Veteran’s Care, Katrina Recovery and Iraq Accountability Appropriations Act (UTRA, P.L. 110-28)

Enacted in May 2007, the legislation appropriated up to $650 billion to close remaining 2007 SCHIP shortfalls as needed and provided authority to the HHS Secretary to direct these appropriations to states.

SCHIP Extension Act (P.L. 110-173)

Enacted in December 2007, the legislation temporarily reauthorized SCHIP through March 31, 2009, with national allotment levels set at $5 billion annually. In addition, a supplemental appropriation of $1.6 billion was targeted to states projecting shortfalls in 2008 and an appropriation of $275 million was targeted to states projecting shortfalls in 2009.

Children’s Health Insurance Program Reauthorization Act (CHIPRA, P.L. 111-3)

Enacted in January 2009, the legislation reauthorized SCHIP for five years (renaming the program “CHIP”), established national allotments that were based on current spending and increased over time, altered the allotment distribution formula to reflect state need, and made other important changes to CHIP’s financing structure.

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA, P.L. 111-148, 111-152)

Enacted in March 2010, the legislation reauthorized CHIP for two years through 2015 and established national allotments for those two years.