Legislation from House Ways and Means Chairman Dave Camp and Senate Finance Committee Ranking Member Orrin Hatch would rescind the federal government’s commitment to provide unemployment insurance (UI) benefits through 2011 to Americans who have been out of work for more than half a year and are still looking for a job. Their bill would both subject unemployed workers and their families to hardship and, by reducing the purchasing power of the unemployed, reduce the demand for the goods and services that businesses produce — slowing the economic recovery and limiting job creation.

Moreover, their legislation does not take any steps to require, induce, or even encourage states to shore up their cash-strapped UI systems for the longer term. It thus would leave those systems highly vulnerable financially when the next recession hits.

The UI system is now under major stress. A majority of states have had to borrow from the federal government during the current economic downturn to pay unemployment insurance benefits, and they now face the substantial cost of repaying those loans, with interest. The first interest payments are due in less than four months, by September 30, and in most states the first principal payments are required early next year. Under federal UI law, taxes on employers are increased automatically in states with outstanding loans, in order to finance the loan repayments.

Raising UI taxes too rapidly poses risks to an economic recovery still struggling to gain traction. At the same time, however, state UI systems are in financial trouble largely because most states kept their UI taxes artificially low in the years when the economy was stronger, before the recession hit. States are supposed to build up their trust fund reserves when times are good so they have ample funds to draw upon when the next recession hits, but most states failed to do that. Federal policymakers should not give states new incentives to once again fail to build up adequate UI reserves after the economy strengthens.

Unfortunately, the Camp-Hatch legislation (the Jobs, Opportunity, Benefits and Services Act of 2011, HR 1745) follows a misguided course in all of these areas. As noted, it would renege on the federal government’s commitment to provide UI benefits for the long-term unemployed through 2011 and would instead transfer $31 billion — the amount the federal government is currently estimated to spend on these benefits through the rest of the year — to the states, which would be free to use the funds for a range of purposes. States could elect to use the funds to continue providing benefits for the long-term unemployed, but they would be under no requirement to do so. States would be permitted to stop providing these benefits altogether, even though the unemployment rate now stands at 9.1 percent, and to use the funds to cut UI taxes on businesses and/or to pay down their loans to the federal government.

The legislation also would lift a moratorium that currently prevents states from reducing their UI benefit levels. Allowing states both to end UI benefits now for long-term unemployed workers and to cut benefits for all unemployed workers who continue receiving benefits would increase hardship for many jobless workers and their families. It also would withdraw purchasing power from the economy at a time when the main cause of continued high unemployment and weak economic growth is insufficient demand for the goods and services that businesses produce. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has said that unemployment insurance helps preserve and create jobs in a weak economy because it “adds to overall demand and raises employment over what it otherwise would have been during periods of economic weakness.”[1]

In addition, the Camp-Hatch bill would leave the UI system vulnerable to the next economic downturn. It does nothing to require or give incentives to states to shore up their UI systems; states could accept the funding windfalls that the bill would confer on them while taking no action to address their long-term UI financing problems. Such an approach would constitute a “moral hazard” — it could lead states to believe they can continue to leave their UI systems heavily underfunded and count on federal loans, followed by federal windfall funding transfers, to bail them out in the future.

Federal policymakers can — and should — chart a different course, one that creates a longer-term framework to help state UI systems prepare for the next recession, while limiting tax increases on businesses over the next couple of years (giving the economic recovery time to gain strength) and protecting UI payments for unemployed workers and their families.[2]

One such forward-looking proposal is the Unemployment Insurance Solvency Act of 2011 (S. 386), introduced by Senator Richard Durbin and a number of other senators. Unlike the Camp-Hatch plan, the Durbin bill (which builds and improves upon a UI financing reform proposal in the Obama 2012 budget) would both protect employers from federal UI tax increases and loan interest payments in the next two years and create strong incentives for states to adequately fund their UI systems in the future. Unlike Camp-Hatch, it would restore the health of state UI financing for future recessions (and reward states already preparing properly for the future) while protecting workers’ UI benefits from drastic and economically counterproductive cutbacks.

Also unlike the Camp-Hatch bill, the Durbin proposal would help reduce the federal deficit. [3] States hold their trust funds in federal accounts, so increases in state trust fund balances improve the federal balance sheet. The Camp-Hatch proposal — which does not include measures to improve state UI financing practices for the future— has virtually no deficit reduction impact.[4]

Unemployment insurance is a joint federal-state program that helps eligible people who have been laid off by replacing part of their wages on a temporary basis.[5] States collect taxes from employers and use the revenues to pay regular UI benefits to unemployed workers. The federal government also collects a small tax (known as the FUTA tax) that goes into a federal UI trust fund. Money from the trust fund is transferred to states to cover UI administrative costs, and states can borrow from the trust fund if they do not have enough money to meet their obligation to pay benefits during economic downturns. The federal government also steps in to provide emergency UI benefits when unemployment is especially high during recessions and the early stages of recoveries.[6]

States also have their own UI trust funds, which they are supposed to build up during periods of low unemployment and healthy economic growth and then draw upon in economic downturns to pay up to 26 weeks of benefits to unemployed workers who lose their jobs through no fault of their own. [7] Unemployment payments sustain laid-off workers and their families, whose spending in turn helps to support the economy at times when consumer demand is weak.

Since the deep 1981-82 recession, however, many states have discarded the fundamental “forward-funding” premise of UI financing.

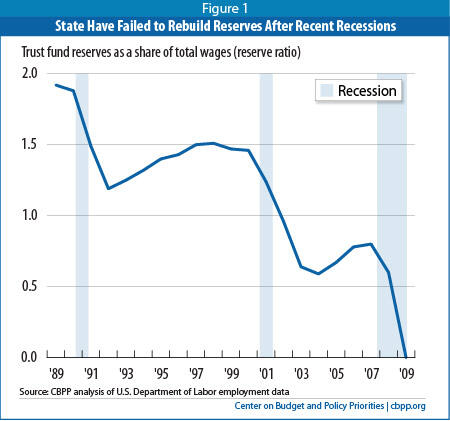

[8] States failed to rebuild adequate UI reserves during the economic expansions that followed the recessions of 1990-91 and 2001 (see Figure 1), and they were forced to borrow heavily from the federal government as their reserves ran out in the current deep economic downturn.

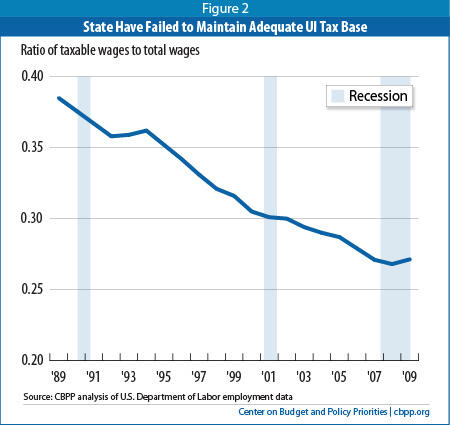

The primary reason that state UI reserves did not recover is that states, under pressure from some business groups, kept UI taxes artificially low even when economic activity picked up. (Among other things, they failed to adequately adjust their taxable wage base — the amount of a worker’s earnings on which the UI tax is levied — to account for inflation and wage growth over time.) As a result, the share of wages that are subject to UI taxes has declined sharply, as Figure 2 shows. [9] States in general have become less well prepared for each successive recession.

In December 2007, when the current economic downturn began, total state UI trust fund reserves equaled just 0.8 percent of total wages. By contrast, state reserves equaled 1.5 percent of wages prior to the 2001 recession and 1.9 percent of wages prior to the 1990-91 recession.

With reserves so low, state UI systems were not adequately prepared for even a moderate recession. They were even less well prepared for the Great Recession that began at the end of 2007.

The recession that started in December 2007 was one of the longest, and by many measures the most severe, since the Great Depression. The unemployment rate peaked at 10.1 percent — near its post-World War II high — and has remained at or above 9 percent for most of the past two years. Local sources of economic stress, such as very high foreclosure rates, have exacerbated economic problems in a number of states.

Most of the minority of states that

did prepare appropriately for this recession (by building up adequate UI trust fund balances while the economy was healthy) have had sufficient reserves with which to pay benefits under their regular state UI programs. When the recession hit, some 17 states — about one-third of the states — had balances that met or exceeded the Department of Labor’s standard for UI trust fund adequacy.

[10] Only

four of these 17 states have needed to borrow more than a small amount from the federal UI trust fund.

[11] (Three of these four states were hit exceptionally hard by the bursting of the housing bubble and the economic downturn — Nevada, Arizona, and Florida. The fourth state is Vermont.)

Of the 33 states that failed to build up adequate reserves before the recession, only four escaped insolvency. Altogether, the trust funds of 35 states became insolvent at least temporarily in the face of high unemployment and consequently had to borrow from the federal government to pay regular UI benefits. Some 28 of these states were still borrowing as of June 7, 2011.

Of particular concern, an economic model we developed with the National Employment Law Project projects that if states maintain their current UI tax and benefit policies, states (in the aggregate) will not begin to move from repaying their federal loans to starting to build their UI reservesuntil 2018,[12] and about a dozen states will still be borrowing ten years from now. [13]

When the next recession hits, those states that have not repaid their debt from today’s downturn will have to borrow additional funds and be forced to go even deeper into debt in order to provide basic UI benefits to unemployed workers. States in this position may need to borrow indefinitely from the federal government. Unless they reform the financing of their trust funds, they could be caught in a cycle of borrowing that they cannot repay between recessions, and ultimately their UI systems — as we know them today — could be in jeopardy of collapse.

The model also predicts that, in addition to the dozen or so states that will enter the next recession still in debt, another 18 states or so are likely to be so poorly prepared that they will return to borrowing during the next recession even if that recession is a relatively mild one. In total, about 30 states are likely to be unprepared to make basic UI payments to unemployed workers in the next recession without borrowing, or borrowing more, from the federal government — even if that recession does not strike for another ten years — unless their financing policies are reformed.

Current law requires the federal government to recoup unpaid balances on the loans it has made to state UI trust funds. If a state does not pay back these loans in full within roughly two years, the federal government raises the annual federal UI tax on employers (known as the FUTA tax) in the state by $21 per employee and applies the resulting revenue toward reducing the state’s loan balance.[14] That deadline for repaying UI loans for most states that have borrowed during the current downturn is November 10, 2011. [15] Businesses in states that do not meet this deadline will see their FUTA taxes rise beginning in early 2012.

Under the law, if the $21 increase proves insufficient — as it will in the vast majority of states — to pay back the state’s loan in the first year this tax increase is in effect (i.e., by November 2012 in most states), the FUTA tax will increase by another $21 per employee beginning in early 2013 (in most borrowing states, the total increase from current levels would be $42 per employee by early 2013). The tax will continue to increase by $21 increments in subsequent years until a state’s loan is repaid.

Even as the federal government increases FUTA taxes to recoup the loans, states will continue to need to rely on their own UI taxes to finance the payment of regular UI benefits, and the number of beneficiaries will continue to be unusually large as long as the economy remains weak and unemployment remains high. As mentioned above, states will also need to raise taxes to build adequate reserves to prepare for the next recession.

Moreover, these FUTA tax increases do not cover the interest that states must pay on these loans. The first interest payments are due on September 30 of this year. About two-thirds of states that have taken loans are planning to assess special taxes on businesses to finance the interest payments.[16] The rest plan to finance these payments through other means, such as using general funds or issuing bonds.[17]

Although the Great Recession technically ended in June 2009, economic growth remains slow, and the labor market faces a long and difficult climb out of the jobs hole the recession created. While the private sector has created an average of over 140,000 jobs a month in the past 15 months, job growth will have to be much stronger to reduce the unemployment rate significantly.[18]

And if combined federal and state UI taxes rise too sharply while the economy remains weak, that could further impede economic recovery by discouraging some businesses from hiring.

The challenge before policymakers thus is to develop a plan that:

- Puts states on a course to rebuild adequate trust funds for future recessions;

- Limits the necessary tax increases for businesses, especially in the near term while the economy remains weak; and

- Protects UI payments for workers and their families.

The Camp-Hatch proposal fails to meet these criteria, as the next section of this analysis indicates, while a proposal from Senator Durbin satisfies these three criteria, as the section after that explains.

The Camp-Hatch proposal neither protects UI payments for workers and their families nor assures that states will prepare better for future recessions. While it almost certainly would result in some tax relief for employers, businesses in a number of states would still be required to pay higher FUTA taxes next year, when the economy is expected to remain weak.

The proposal also would renege on the federal government’s promise of UI benefits this year for the long-term unemployed. Instead, it would transfer $31 billion — the amount the federal government currently is estimated to spend on these benefits through the end of the year — to the states, which could use these funds for other purposes.

Even in states that did use the funds to continue providing benefits for the long-term unemployed, the funds could prove insufficient, forcing a number of those states to curtail benefits. (See the box on page 9.)

Moreover, states would be allowed to stop providing UI benefits to long-term unemployed workers altogether and to use the money to pay for regular UI benefits (in order to cut or keep from increasing business taxes), pay down their federal UI loans, deposit the money in their trust funds, or finance various employment services. The legislation would also lift a moratorium that currently prevents states from cutting UI benefit levels.

Camp-Hatch would let states that failed to prepare adequately for the recession off the hook. It would grant them large sums without requiring them to strengthen their UI financing systems for the future and prepare adequately for the next recession. Many states would likely accept their federal windfall while continuing to ignore their long-term financing problems.[19]

Ten states in debt to the federal government would receive enough federal funding under Camp-Hatch to pay back their outstanding balances in their entirety.[20] The remaining 18 states that currently have outstanding loans would be able to pay off part, but not all, of their debt; businesses in those states would remain subject to FUTA tax increases in the next couple of years to cover the remainder of their state’s debt, despite the weak state of the economy.

States also could deposit the money in their UI trust funds, where it could be used to pay regular UI benefits for the unemployed. Shoring up trust fund balances in this way would reduce the taxes that businesses will otherwise have to pay over the next few years. But it would do nothing to rebuild states’ trust funds for future recessions and would fail to address the underlying weaknesses in UI financing that mark many states’ systems. In fact, since the plan could encourage some states to cut their UI taxes, it could leave them even less prepared for the next recession.

Camp-Hatch Would Require Some States to Use Their Own Funds to Continue Benefits for Long-Term Unemployed

Materials released with the Camp-Hatch proposal assert that under the plan, states could continue to provide benefits for the long-term unemployed “and have all the money they need to do so.”* This is not necessarily true. Not only could the total amount allocated to states be insufficient, but the formula used to distribute the funds among states likely undercompensates those states that are still struggling to recover from the recession, while overcompensating states that are recovering more rapidly.

The amount allocated to states — $31 billion — is based on the Congressional Budget Office’s estimate of projected need and therefore reflects certain assumptions about national economic conditions through the end of the year. If the need for benefits among the long-term unemployed turned out to exceed current expectations, that amount would be too low.** In that case, the funds allocated to states would be insufficient to pay the benefit to all who previously would have been eligible, but no additional federal funds would be forthcoming.

The distribution of funds is based on past economic conditions, so some states would inevitably receive less than they would need even if the total amount of funds proved sufficient nationally. The bill would allocate each state’s share of the $31 billion based on that state’s share of the federal emergency benefits (both Emergency Unemployment Compensation and Extended Benefits) paid over the previous 12 months. The relative need in each state over the next half year, however, will not be identical to what it was over the past 12 months. As a result, some states would receive less than they needed to continue providing the benefits promised to the long-term unemployed, while other states could receive more than needed for that purpose.*** States receiving less than they needed would be forced to use their own funds if they wished to continue providing the benefits.

* See Ways and Means Committee, “Highlights of the JOBS Act,” May 5, 2011, http://waysandmeans.house.gov/UploadedFiles/JOBS_Act_2011_Highlights.pdf.

** The cost estimate notes that the total amount transferred to states in the Camp-Hatch proposal would be slightly less than the amount CBO projects states will spend on EUC and EB under current law. On net, CBO found that the proposal would slightly reduce the deficit. See Congressional Budget Office, “H.R. 1745: Jobs, Opportunity, Benefits, and Services Act of 2011,” May 23, 2011, http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/122xx/doc12208/hr1745.pdf.

*** See letter from Jane Oates, Assistant Secretary of Labor, to Representative Sander Levin, May 26, 2011, http://democrats.waysandmeans.house.gov/media/pdf/112/26May_Levin_Labor_Letter.pdf.

Impeding Economic Recovery and Increasing Hardship

Allowing states to divert funding for UI benefits for the long-term unemployed to other purposes would have adverse effects on both workers and the economy. The economy continues to need the boost that federal emergency UI benefits provide, and workers struggling to find jobs in a tough labor market continue to need assistance. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has found that UI is one of the most effective measures available for preserving and creating jobs in a weak economy.[21]

If states instead use the money to keep business taxes lower, either by paying off their loans or depositing the money in their trust funds, that would do less to give the economy the short-term boost it needs.[22]

Moreover, the Camp-Hatch provision to lift the moratorium that restricts states from cutting benefit amounts likely would lead some states to cut benefits this year, reducing the income of unemployed workers and further impeding the economic recovery.

It should be noted that a stunning 45 percent of the workers now unemployed have been out of work for more than 26 weeks. This is a far higher percentage than during or following any previous recession, with the data going back to 1948. Allowing states to take away a crucial source of income for millions of unemployed workers would increase hardship for workers and their families.

In summary, the Camp-Hatch proposal could limit some tax increases on businesses in the short term, but it fails to meet the other two key criteria discussed above: it neither puts states on a path to UI solvency nor protects UI benefits for unemployed workers.

Policymakers have better options. Congress can create a framework to help states prepare for the next recession, while limiting tax increases on businesses over the next couple of years and protecting UI benefits for workers and their families.[23] One such forward-looking proposal is the Unemployment Insurance Solvency Act of 2011, S. 386, which Senate Majority Whip Richard Durbin and other senators recently introduced.

That measure would allow employers to entirely avoid both federal UI tax increases and state tax increases to finance loan interest payments over the next two years, when the economy is expected to remain weak, while putting states on a path toward long-term solvency. It would do so by allowing states to have part of their current federal loans forgiven, which would save employers as much as $37 billion in federal unemployment taxes over the next few years — but only in exchange for adequate state action to rebuild their UI financing systems so they are better prepared for future recessions. It would also provide rewards, including a federal tax cut, for businesses in states that adequately fund their UI systems, as a further incentive for such state action.

The Unemployment Insurance Solvency Act also would protect unemployed workers and their families; unlike the Camp-Hatch plan, it would not disrupt the federal UI benefits being provided this year to the long-term unemployed or allow immediate cuts in UI benefit levels. And by helping to ensure that state trust funds are adequate, it would help sustain consumer demand in future downturns.

Finally, it would take these steps in ways that would reduce the federal budget deficit.[24] That’s because once the economy is stronger, states would need to build up their trust funds in preparation for the next recession. Because states hold their trust funds in federal accounts, any increase in state trust fund balances improves the federal balance sheet. Since the increase in UI trust fund balances would exceed the cost of forgiving a portion of states’ loans, the plan overall would reduce the federal budget deficit.

Policymakers need to develop a plan to relieve the stress on state UI trust funds. But allowing states to pay down their loans without requiring them to better finance their systems in the future would not be responsible policy. And financing such assistance to states by taking money away from the long-term unemployed, and thereby increasing the drag on the current weak economy, would be especially ill-advised.

There are much sounder approaches. In particular, the Unemployment Insurance Solvency Act would help restore the UI system’s long-term financial health while protecting employers from tax increases now while the economy is weak and sustaining UI payments for the unemployed.