- Home

- An Overview Of Issues Raised By The Admi...

An Overview of Issues Raised by the Administration's Social Security Plan

This analysis is based on the briefing on the Administration’s Social Security plan that was provided to reporters on February 2 by a “senior Administration official.”

1. Administration Acknowledges Private Accounts Would Do Nothing to Improve Social Security Solvency.

The Administration official acknowledged what analysts have long known — private accounts themselves do nothing to restore solvency. The official stated:

- “So in a long-term sense, the personal accounts would have a net neutral effect on the fiscal situation of the Social Security and on the federal government.” [Transcript, page 5.]

- A reporter subsequently asked the senior Administration official: “. . . am I right in assuming . . . that it would be fair to describe this as having — the personal accounts by themselves, that it would be fair to describe this as having — the personal accounts by themselves as having no effect whatsoever on the solvency issue?” The senior Administration official replied: “That’s a fair inference.” [Transcript, page 7.]

2. Claimed $750 Billion Estimate Makes Borrowing Costs Look Much Lower Than They Actually Would Be.

The senior official said the borrowing costs over the first ten years — 2006- 2015 — would be $664 billion without interest costs, and $754 billion when interest costs on the debt are included.

These figures are misleadingly low. They are generated by using a ten-year budget window (2006- 2015) that includes only five years of the fully phased-in plan. The plan would not be launched until 2009 and not be in full effect until 2011.

Over the first ten years that the plan actually was in effect (2009-18), it would add about $1.4 trillion to the debt. Over the next ten years (2019- 28), it would add about $3.5 trillion more to the debt. All told, the plan would add $4.9 trillion (14 percent of GDP in 2028) to the debt over its first 20 years.

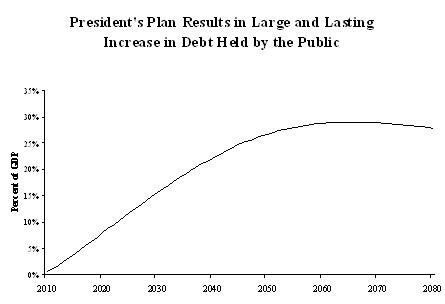

The additional debt resulting from the President’s proposal would continue to rise as a share of the overall economy, reaching more than 25 percent of GDP in about 40 years and remaining at or above that level for the entire 75-year projection period (see Figure).[1]

Although the senior Administration official contends that the plan would be fiscally neutral in the long-run, the figure shows that the individual accounts in the President’s plan would add to government financing needs for many decades into the future. These debts would need to be financed annually, unlike the implicit debt we owe to Social Security beneficiaries.

Furthermore, these estimates are based on the assumption that the individual accounts are offset by 50 percent reductions in guaranteed benefits for average earners, as envisioned in the plan. This cut would offset the entire value of the individual account for the typical worker. If these cuts prove politically unsustainable and get scaled back by future Congresses, the plan would have an even larger impact on the debt and would result in worsening of even the very long-run fiscal situation.

3. White House Declines to Propose Measures to Restore Solvency

At the briefing, the senior Administration official declined to offer any proposals to close Social Security’s shortfall, despite acknowledging that the private accounts would themselves do nothing to close it. The official punted on the issue, indicating it was something for the Administration and Congress to work out subsequently.

The principles that the President directed his Social Security Commission to follow, and that he subsequently reaffirmed, call for no new revenue-raising measures to help close the shortfall. If revenues are ruled out, however, the $3.7 trillion, 75-year gap would have to be closed entirely through cuts in Social Security benefits.

The one proposal that the President’s Social Security Commission advanced to close the gap through benefit cuts was to change the formula for computing initial Social Security benefits from one that uses “wage indexing” to one that uses “price indexing.” Administration officials have talked up this proposal in recent weeks. If the Administration uses price indexing to restore actuarial balance, then the benefit reductions under the plan that the Administration otherwise outlined today would be very large. For instance, a worker born in 2000 who has average wages, participates in the private accounts, and retires in 2065, would have total benefits (from Social Security and the private account) that are 50 percent below the Social Security benefit scheduled under current law (and 34 percent below what Social Security would be able to pay even if no steps are taken to restore solvency). This estimate and others shown in the table below use the Congressional Budget Office’s methodology for computing the benefits levels under the proposed private accounts and price indexing.

| Benefit Cuts With Price Indexing and the Private Accounts That the White House Described Today | |||||

| First-Year Annual Benefits for the Median Worker in Middle of the Income Scale | |||||

| 10-Year Birth Cohort Starting in Year | Current Law Benefits | White House Plan, with Price Indexing | |||

| Scheduled Benefits ($2004) | Payable Benefits ($2004) | Benefits (Social Security Plus Private Accounts) ($2004) | Percentage Reduction, Compared to Scheduled Benefits | Percentage Reduction, Compared to Payable Benefits | |

| 1940 | $14,900 | $14,900 | $14,840 | -0.4% | -0.4% |

| 1950 | 15,200 | 15,300 | 13,994 | -8% | -9% |

| 1960 | 15,500 | 15,500 | 12,742 | -18% | -18% |

| 1970 | 17,700 | 17,700 | 12,841 | -27% | -27% |

| 1980 | 20,500 | 19,700 | 13,097 | -36% | -34% |

| 1990 | 23,300 | 18,100 | 13,104 | -44% | -28% |

| 2000 | 26,400 | 19,900 | 13,092 | -50% | -34% |

| Source: The columns for scheduled and payable benefits are taken directly from CBO, “Long-term Analysis of Plan 2 of the President’s Commission to Strengthen Social Security,” 2004. The columns on the plan are calculated using CBO assumptions and methodology, assuming the change to price indexing goes into effect in 2011 and that the individual account offset rate is set at 3 percent (the rate the Social Security actuaries project for Treasury bonds). The benefits are for a worker who initially claims benefits at age 65. | |||||

4. Private Accounts Would Provide No Gain to Workers Unless The Accounts Earned a Rate of Return Equal to More than 3 Percent Above the Inflation Rate.

The senior Administration official revealed that most of the balances in a worker’s account would be recaptured by the government when the worker retired, in order to repay Social Security for the loss of revenue it incurred when a worker elected to direct some of his or her payroll taxes from the Social Security Trust Fund to a private account.

The senior Administration official explained that this repayment would be made by subjecting people who elected the private accounts to an additional reduction in their Social Security benefits (over and above any cuts that may be imposed to restore solvency). The additional benefit reduction would be made by lowering these individuals’ Social Security benefits each month by an amount equal to the monthly income that would come from their account if the account had earned a three percent real rate of return (the assumed rate of interest on Treasury bonds). As a result of this additional benefit reduction, people opting for the accounts would get no net gain from the accounts unless their accounts produced a return higher than three percent above the inflation rate. If the return on their accounts was lower than three percent above the inflation rate, people would lose money as a result of the private accounts, and that loss would be on top of the other Social Security benefit cuts (such as price indexing) to which they were subjected. (The senior official stated in the briefing: “So, basically, the net effect on an individual’s benefits would be zero if his personal account earned a 3 percent real rate of return.” A reporter then asked: “So he would only get a benefit to the extent that his portfolio performed in excess of 3 percent [above inflation]?” The senior official replied: “Right.” See transcript, page 8.)

As a result, for many workers, the private accounts in the plan would not offset any of the reductions in Social Security benefits that would be part of the plan. For these workers, their entire private account balance would be recaptured by the government when they retired.

End Notes

[1] Traditionally, the Social Security actuaries release a memo showing the impacts of Social Security proposals over 75 years. In this case, the actuaries memo shows only 10 years of the plan (see Stephen Goss, Chief Actuary, Social Security Administration, “Preliminary Estimated Effects of a Proposal to Phase In Personal Accounts,” February 3, 2005). As a result, all estimates in this paper are based on a conservative extrapolation of the data past the first 10 years.

Specifically, the White House has not formally decided what happens to the maximum account contribution after 2015, although Administration officials have stated that, “Yearly contribution limits would be raised over time, eventually permitting all workers to set aside 4 percentage points of their payroll taxes in their accounts.” All estimates here assume conservatively that the contribution limits would not continue to be raised after 2015 (beyond the standard indexing for wage inflation) and thus that the accounts would be less than four percent for many middle and upper-income workers. With four percent accounts for everyone, the adverse fiscal impacts of the plan would be larger; for example, the plan would add $5.1 trillion to the debt over its first 20 years (2009-2028), rather than $4.9 trillion.

More from the Authors