On June 26, 2009, the House of Representatives approved the American Clean Energy and Security Act of 2009 (H.R. 2454). This legislation, which would place a cap on emissions of greenhouse gases to combat global warming, includes important provisions to ensure it does not make large numbers of low-income families worse off. These provisions would fully offset the loss of purchasing power that low-income households as a group would face. [1]

These provisions are important and well designed. Nevertheless, the legislation could take additional steps to protect those low-income households, such as people living in older, very poorly insulated homes, whose energy costs will increase by significantly more than the amount of the relief they would receive. That could be accomplished by dedicating a small share of revenue the legislation could raise — such as 1 percent of the permit value — to increase the funding for the Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP). LIHEAP is a federal program that provides financial assistance to help low-income households heat and/or cool their homes. A portion of LIHEAP funding also can be used to weatherize low-income households’ residences.

Restricting activities that produce greenhouse-gas emissions is necessary to avoid costly and potentially catastrophic environmental and economic consequences from global warming, but it also will raise the costs of fossil-fuel energy and of goods and services that use such energy in their production or transport to market. Low-income consumers are the most vulnerable to the higher costs arising from climate change policy because they spend a larger share of their budgets on necessities like energy than do better-off consumers, already face challenges making ends meet, and are the least able to afford new, more energy-efficient appliances or vehicles.

The legislation includes important provisions to protect vulnerable households’ budgets, while still achieving the benefits of reduced emissions. Consumer relief is provided in several forms.

First, retail gas and electric utilities (also called local distribution companies, or LDCs) are given substantial resources (in the form of free emissions allowances), with instructions that a specified portion of such allowances be used for the benefit of residential customers and with a disproportionate share of these resources going to regions of the country where electricity prices are expected to rise the most. This relief will be spread broadly across all residential consumers, regardless of their income.

Low-income households would receive additional assistance primarily through an “energy refund” that state human service agencies would administer, with the assistance levels being adjusted by household size. Low-income workers without children, who would be less likely to be reached through the state human services agencies, would be compensated through an adjustment in the component of the Earned Income Tax Credit that serves those workers. Combined, these mechanisms — along with the relief provided through the LDCs — would fully offset the increased expenses for the average household in the bottom fifth of the income distribution.

The House bill provides low-income households (those with incomes up to 150 percent of the poverty line, or about $33,000 for a family of four in 2009), with a standard energy refund amount, based on the number of people in the household.[2] This is the only way a broad-based program designed to reach tens of millions of lower-income households can operate; neither the tax code nor a benefit program serving tens of millions of Americans can vary the benefit based on each individual household’s actual increase in costs. [3] Under this structure, however, a modest portion of low-income families may face significantly higher costs than they are compensated for through the consumer relief provided under the House bill. In particular, some individuals who rent poorly insulated apartments (or own poorly insulated homes) or have older, less efficient appliances may be less than fully compensated by the bill’s consumer relief provisions. Some of these households could have increased difficulty making ends meet, even with the important consumer assistance the bill provides.

Supplemental assistance is needed to cushion the blow on such households. Such supplemental assistance could be provided by devoting a modest portion of the allowance value under the legislation, such as 1 percent of the permit value, for increased funding for the Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program.[4] Such funding also could provide aid to low-income households that “fall through the cracks” and do not receive help from the energy refund or the increase in the Earned Income Tax Credit. There should not be large numbers of such households, but there inevitably will be some.

In short, LIHEAP funding would provide a safety net for poor households that do not otherwise receive adequate assistance and may otherwise face utility shut-offs or other hardships.

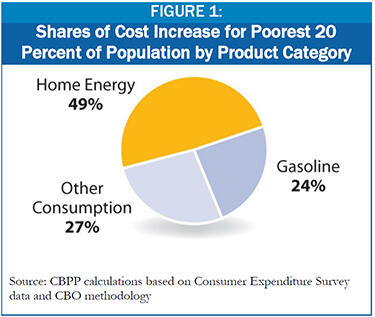

LIHEAP is limited in size and scope and could not serve as a main engine for consumer relief in climate-change legislation. [5] It reaches only a modest fraction of low-income households, has widely varying benefit and eligibility standards, and addresses only costs associated with home energy consumption, which will constitute less than half of the increased expenses that low-income consumers will bear under an emissions cap (see Figure 1).

LIHEAP is well-suited, however, to the role of providing supplemental assistance for those low-income consumers that face particular hardship because of extremely high energy costs. The LIHEAP statute already requires that funds be used to assist households with the lowest incomes and highest energy costs or needs in relation to income. In fiscal year 2006, low-income households overall had average energy expenditures of $1,690, but the households receiving LIHEAP funding had average energy expenses of $1,992, nearly 18 percent higher.[6]

LIHEAP is administered by state or local agencies that are accorded significant flexibility over program design and implementation. LIHEAP can thus be administered in a way that allows it to deal with case-by-case problems for families or individuals who might otherwise fall through the cracks. LIHEAP funds also do relatively well at reaching low-income households with elderly individuals.[7]

For these reasons, a provision to devote an amount equal to roughly 1 percent of the allowance value to increased funding for LIHEAP, with the funds used to supplement the bill’s basic relief for low-income consumers and to fill gaps and cracks, would strengthen the low-income provisions of the legislation.

Low-income households with particularly large energy costs also would benefit from additional funding for low-income weatherization assistance. The House bill allocates allowances for State Energy and Environment Development Accounts, with a portion of those funds to be used for a variety of energy-efficiency investments. Currently, the bill requires states to set aside a very small share of these allowances (amounting to 0.05 percent of the total allowance value) to improve energy efficiency in subsidized housing.[8] This component of the legislation could be strengthened by requiring a larger percentage of allowances be used for subsidized housing. In addition, a portion of allowances allocated to states could be set aside to benefit low- and moderate-income households generally.[9]