- Home

- 2010 Medicare Trustees’ Report Shows Ben...

2010 Medicare Trustees’ Report Shows Benefits of Health Reform and Need for Its Successful Implementation

The 2010 annual report of Medicare’s trustees clearly demonstrates that the Affordable Care Act (or ACA, the recently enacted health reform legislation) has greatly improved the financial status of the Medicare program.[1] It also shows that successful implementation of the ACA is an essential first step toward slowing the growth of health care costs.

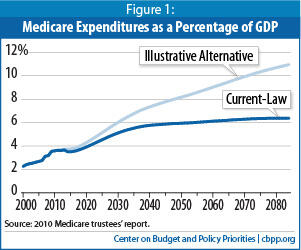

At the same time, the trustees’ report points out the major challenges ahead as the population ages and health care costs continue to rise. Even if all the provisions of the ACA are successfully put in place, Medicare expenditures will rise substantially in coming decades and strain the federal budget. To ease pressure on the budget, it will be necessary not only to implement health reform faithfully, but also to take further very large steps to curb the growth of health costs system-wide as we learn more (partly from the research and pilot projects that health reform requires) about how to do so effectively.

The Affordable Care Act has strengthened Medicare’s financing in both the short and the long run. Medicare’s Hospital Insurance (HI, or Part A) Trust Fund is now projected to remain solvent through 2029 — an improvement of 12 years compared to last year’s projection. The improvement reflects the efficiency savings and additional revenues enacted in the ACA. Even under a more pessimistic “illustrative alternative scenario,” under which a significant share of these savings are not sustained, the trustees project that the HI trust fund will remain solvent through 2028. [2]

The trustees also report that health reform has closed half to four-fifths of HI’s long-term shortfall, depending on the extent to which the law’s savings are realized. Under the trustees’ main projection, the program’s 75-year shortfall has shrunk from 3.88 percent of taxable payroll (total earnings subject to Medicare payroll taxes) in last year’s trustees’ report to 0.66 percent in this year’s report. Even under the trustees’ alternative scenario, which assumes that only 60 percent of the ACA’s savings are achieved in the long run (the scenario that Medicare actuary Richard Foster believes is more realistic), half of the long-term shortfall has been closed by this one piece of legislation.

Medicare’s Supplementary Medical Insurance (SMI) Trust Fund consists of two separate accounts — one for Part B of Medicare, which pays for physician and other outpatient health services, and one for Part D, which pays for outpatient prescription drugs. By its design, SMI is always adequately financed because beneficiary premiums and general revenue contributions are set at the levels necessary to cover expected costs each year. By slowing the growth of costs, the ACA has reduced the projected premiums that beneficiaries will have to pay, as well as the required general revenues.

Even if further steps are taken to slow the growth of health care spending below the current-law projections, however, the built-in growth in Medicare — as well as that in Medicaid and Social Security — will drive up federal spending in coming decades. This will make it all but impossible to hold total federal spending to historical average levels — as some lawmakers and pundits have recommended — without making draconian cuts in those programs and an array of other vital federal activities.[3]

Nonetheless, the trustees’ new projections are more favorable than most in recent years. Over the past 21 trustees’ reports, changes in the law, the economy, and other factors have brought the projected year of HI insolvency as close as four years away or pushed it as far as 28 years into the future (see Table 1). The new projection falls toward the favorable end of that spectrum. Trustees’ reports have been projecting impending insolvency for more than 35 years, but Medicare benefits have always been paid because Congress has taken steps to keep spending and resources in balance. In contrast to Social Security, which has had no major changes in law since 1983, the rapid evolution of the health care system has required frequent adjustments to Medicare, and that pattern is certain to continue.

| Table 1: Projections of Medicare HI Insolvency Have Varied Substantially | |||||

| Year of Trustees’ Report | Projected Year of Insolvency | Year of Trustees’ Report | Projected Year of Insolvency | Year of Trustees’ Report | Projected Year of Insolvency |

| 1990 | 2003 | 1997 | 2001 | 2004 | 2019 |

| 1991 | 2005 | 1998 | 2008 | 2005 | 2020 |

| 1992 | 2002 | 1999 | 2015 | 2006 | 2018 |

| 1993 | 1999 | 2000 | 2025 | 2007 | 2019 |

| 1994 | 2001 | 2001 | 2029 | 2008 | 2019 |

| 1995 | 2002 | 2002 | 2030 | 2009 | 2017 |

| 1996 | 2001 | 2003 | 2026 | 2010 | 2029 |

| HI: Medicare's Hospital Insurance Trust Fund (Medicare Part A) Source: Trustees’ reports, various years. | |||||

Contrary to a common misconception, the improvement in Medicare’s financing occurs without any reduction in the program’s guaranteed benefits. In fact, the ACA adds important new benefits to Medicare. It gradually closes the “donut hole” for prescription drugs and improves the low-income subsidy for drug coverage. It also expands Medicare’s coverage of preventive services, including an annual wellness check-up and recommended screenings and immunizations.

Claims that the Medicare savings in the ACA have somehow been “double counted” are without merit. The outlooks for the budget and for the HI trust fund are two very different things, but under longstanding federal budget and accounting rules, changes in HI affect both. The Congressional Budget Office has estimated that the Affordable Care Act will reduce the federal deficit by $143 billion over the 2010-2019 period and by approximately $1.3 trillion in 2020-2029.[4] At the same time, the trustees’ report confirms that health reform has also extended the life of the HI trust fund by more than a decade. No double-counting occurs here.[5]

Deficit-reduction legislation that includes Medicare provisions has been accounted for in exactly the same way in previous Congresses under both political parties. For example, both the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 and the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 (both of which were passed by Republican Congresses) included Medicare savings that reduced the federal deficit and improved the solvency of Medicare’s HI trust fund. No claims of double-counting were raised when these bills were enacted. Similarly, the Social Security Amendments of 1983 reduced the budget deficit at the same time as they improved the solvency of the Social Security trust funds.

As the trustees observe, the new Medicare projections emphasize “the importance of making every effort to make sure that ACA is successfully implemented.” The ACA slows the growth of Medicare spending in several ways. It greatly scales back the large overpayments Medicare makes to the private Medicare Advantage health plans that serve some beneficiaries.[6] It also reduces Medicare’s annual payment updates to hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, and certain other fee-for-service providers, in part to account for economy-wide increases in productivity.

The trustees’ report notes that sustaining these payment reductions year after year will require making the health care payment and delivery systems more efficient. That’s why the ACA takes important steps to move away from paying providers for more visits or procedures and toward rewarding effective, high-value health care. Most of these provisions are not estimated to save much money in the next ten years because their effects — while promising — are unproven. Nevertheless, they represent important initial efforts to slow the growth of health care costs.

The health reform law also creates health insurance exchanges that will promote competition among insurers based on the cost and quality of their products. It includes an excise tax on high-cost health plans that promises to help slow the growth of private health care costs. Other provisions that could start to “bend the cost curve” include imposing an excise tax on high-cost insurance plans, establishing an independent agency to research the comparative effectiveness of different medical treatments and items, emphasizing prevention and wellness activities, strengthening primary care, reducing avoidable hospital readmissions, promoting accountable care organizations, and starting pilot programs to bundle Medicare payments for services that hospitals and post-acute care providers deliver during an episode of care.

The new law also creates a Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation to test and evaluate new payment and service delivery models. The Secretary of Health and Human Services can expand the scope and duration of the approaches tested, including nationwide implementation, without any congressional action, if they are found to reduce spending without reducing the quality of care.

In addition, an Independent Payment Advisory Board is charged with developing and submitting proposals to slow the growth of Medicare and private health care spending and improve the quality of care. If the projected growth in Medicare costs per beneficiary exceeded a specified target level — which it almost certainly would do in many years — the board is required to produce a proposal to eliminate the difference. The board’s recommendations will go into effect automatically unless both houses of Congress passes, and the President signs, legislation to modify or overturn them, or if Congress overrides a presidential veto.

Efforts to slow the growth of health care costs must target both public programs and private health insurance, although Medicare can serve as a model for efforts to slow the growth of costs in the rest of the health care system. Medicare and private health spending are growing rapidly for the same reason — increases in the cost and use of medical services. For decades, increases in Medicare costs per beneficiary have mirrored the increases in costs in the health system as a whole. Between 1970 and 2008, Medicare spending for each enrollee rose by an average of 8.3 percent annually, and private health insurance spending rose by 9.3 percent per person per year. [7]

The similarity in growth rates between Medicare and private insurance is not surprising, because Medicare aims to provide its beneficiaries with access to the same doctors, hospitals, and services as the rest of the population. As David Walker, former Comptroller General, has emphasized, “[F]ederal health spending trends should not be viewed in isolation from the health care system as a whole. For example, Medicare and Medicaid cannot grow over the long term at a slower rate than cost in the rest of the health care system without resulting in a two-tier health care system.” [8]

Trying to solve Medicare’s long-term financing problems primarily by reducing benefits, limiting eligibility, increasing cost-sharing, or capping Medicare expenditures would shift costs to elderly and disabled beneficiaries and could reduce their access to health care providers. These approaches have serious limitations because many Medicare beneficiaries are financially vulnerable and already face substantial out-of-pocket medical costs. Most Medicare beneficiaries live in families with modest incomes. In 2008, 67 percent of Medicare’s non-institutionalized beneficiaries had annual family incomes of less than $50,000. Only 15 percent had incomes of $85,000 or more. [9]

Such changes could also have a particularly damaging effect on the small group of Medicare beneficiaries with large medical needs. In 2006, the top 10 percent of fee-for-service beneficiaries accounted for nearly three-fifths (58 percent) of all program expenditures, incurring average costs of $48,000.[10]

The new trustees’ report shows that if the Medicare savings in the Affordable Care Act can be achieved, the program’s financial status will be greatly improved. Even if there is some slippage, however, as in the trustees’ alternative scenario, the improvement will still be substantial. Administrators and policymakers will need to engage in continued efforts both to achieve the maximum possible benefit from the cost controls included in health reform and also to pursue further reforms to slow the growth in both public and private health care costs.

End Notes

[1] 2010 Annual Report of the Boards of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Funds , August 5, 2010, http://www.cms.hhs.gov/ReportsTrustFunds/downloads/tr2010.pdf.

[2] “Projected Medicare Expenditures under an Illustrative Scenario with Alternative Updates to Medicare Providers,” Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Office of the Actuary, August 5, 2010, http://www.cms.gov/ReportsTrustFunds/downloads/2010TRAlternativeScenario.pdf .

[3] Paul N. Van de Water, Federal Spending Target of 21 Percent of GDP Not Appropriate Benchmark for Deficit-Reduction Efforts, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 28, 2010, https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/7-28-10bud.pdf.

[4] Paul N. Van de Water, How Health Reform Helps Reduce the Deficit, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 10, 2010.

[5] James R. Horney, “Charge That Health Reform’s Supporters Are Double-Counting Medicare Savings Is Nonsense,” Off the Charts Blog, August 6, 2010 .

[6] January Angeles, Health Reform Changes to Medicare Advantage Strengthen Medicare and Protect Beneficiaries, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, July 27, 2010.

[7] Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “NHE [National Health Expenditure] Web Tables,” January 2010, table 13, http://www.cms.hhs.gov/NationalHealthExpendData/downloads/tables.pdf . The cited figures refer to benefits commonly covered by Medicare and private health insurance.

[8] David M. Walker, “Long-Term Fiscal Issues: The Need for Social Security Reform,” Statement before the Committee on the Budget, U.S. House of Representatives, February 9, 2005 (GAO-05-318T), p. 18.

[9] CBPP analysis of the Census Bureau’s March 2009 Current Population Survey.

[10] Kaiser Family Foundation, Medicare: A Primer, April 2010, p. 16, http://www.kff.org/medicare/upload/7615-03.pdf.