Statement by Chad Stone, Chief Economist, on the October Employment Report

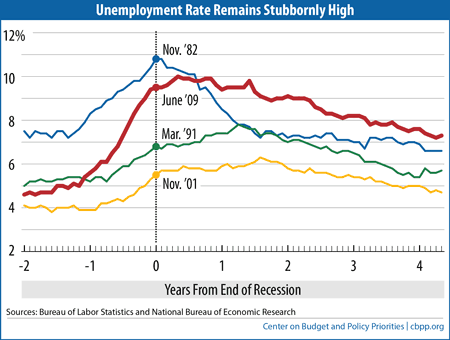

Today’s jobs report, which is colored by October’s federal government shutdown, sends distinctly mixed signals about the job market. The employer survey shows much greater job creation than analysts expected, while the household survey shows that significant weaknesses persist. Either way, unemployment remains stubbornly high (see chart), and too many people have been out of work too long.

That means that congressional budget negotiators must aim higher than just avoiding another government shutdown as they seek an agreement; they must find a way to remove sequestration’s chokehold on the economic recovery while continuing to ease the plight of the long-term unemployed by extending federal emergency unemployment insurance (UI).

The monthly jobs report includes data from two different surveys. One asks employers for the number of jobs on their payrolls; the other asks people whether they are working or looking for work. By and large, federal government employees who didn’t work due to the shutdown were still considered employed in the employer survey but were considered temporarily unemployed in the household survey. The shutdown also delayed data collection. These factors increase the range of uncertainty around the October estimates.

Many effects of the government shutdown on the October jobs numbers could be reversed in November. What won’t be reversed without congressional action is the drag that premature budget austerity, in the form of the sequester and earlier budget cuts, is having on the economic recovery. Moody’s Analytics chief economist Mark Zandi finds, “The economic drag from fiscal austerity is greater than at any time since just after World War II.” The economic forecasting firm Macroeconomic Advisers estimates that the spending contraction since 2010 has raised the unemployment rate by 0.8 percentage point — the equivalent of 1.2 million lost jobs.

Policymakers can reduce that drag by replacing sequestration with back-loaded deficit-reduction measures that don’t begin to take effect until the economy is stronger.

Long-term unemployment (defined as lasting 27 weeks or more) has been far more prevalent in recent years than at any other time in the postwar period. A stronger job market is the key to reducing long-term unemployment.

In the meantime, policymakers should reauthorize federal emergency UI, which is scheduled to expire at the end of the year. That program, which provides additional weeks of UI to people who have run out of their regular state benefits (typically after 26 weeks), not only helps relieve hardship among those jobseekers and their family; it’s also widely recognized as one of the most cost-effective measures for increasing demand and stimulating job creation in a weak economy.

About the October Jobs Report

Job growth in October was much higher than analysts expected. Nevertheless, employment levels remain far below what they would be in a healthy labor market.

- Private and government payrolls combined rose by 204,000 jobs in October and the Bureau of Labor Statistics revised job growth in August and September upward by a total of 60,000 jobs. Private employers added 212,000 jobs in October, while government employment fell by 8,000. Federal government employment fell by 12,000, state government employment rose by 7,000, and local government fell by 3,000.

- This is the 44th straight month of private-sector job creation, with payrolls growing by 7.8 million jobs (a pace of 178,000 jobs a month) since February 2010; total nonfarm employment (private plus government jobs) has grown by 7.2 million jobs over the same period, or 164,000 a month. Total government jobs fell by 608,000 over this period, dominated by a loss of 354,000 local government jobs.

- Despite 44 months of private-sector job growth, there were still 1.5 million fewer jobs on nonfarm payrolls and 1.0 million fewer jobs on private payrolls in October than when the recession began in December 2007. October’s job growth reached into the lower range of the sustained job growth of 200,000 to 300,000 a month that would mark a robust jobs recovery. Similarly, job growth over the past three months has averaged 202,000, a slight uptick from earlier in the year.

- The unemployment rate was 7.3 percent in October, and 11.3 million people were unemployed. The unemployment rate was 6.3 percent for whites (1.9 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession), 13.1 percent for African Americans (4.1 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession), and 9.1 percent for Hispanics or Latinos (2.8 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession).

- The recession drove many people out of the labor force, and lack of job opportunities in the ongoing jobs slump has kept many potential jobseekers on the sidelines. On the surface, October’s figures show things getting worse, but at least part of that reflects temporary job losses due to the shutdown, which should be reversed in November. The labor force (people aged 16 or over working or actively looking for work) shrank by 720,000 and the number of people at work fell by 735,000. As a result, the labor force participation rate (the share of people aged 16 and over in the labor force) fell to 62.8 percent in October, 0.8 percentage points lower than at the start of the year and the lowest since 1978.

- The share of the population with a job, which plummeted in the recession from 62.7 percent in December 2007 to levels last seen in the mid-1980s and has remained below 60 percent since early 2009, dropped to 58.3 percent in October. The decline arising from temporary losses due to the shutdown should also be reversed next month.

- The Labor Department’s most comprehensive alternative unemployment rate measure — which includes people who want to work but are discouraged from looking (those marginally attached to the labor force) and people working part time because they can’t find full-time jobs — was 13.8 percent in October. That’s down from its all-time high of 17.1 percent in late 2009 and early 2010 (in data that go back to 1994) but still 5.0 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession. By that measure, nearly 22 million people are unemployed or underemployed.

- Long-term unemployment remains a significant concern. Nearly two-fifths (36.1 percent) of the 11.3 million people who are unemployed — 4.1 million people — have been looking for work for 27 weeks or longer. These long-term unemployed represent 2.6 percent of the labor force. Before this recession, the previous highs for these statistics over the past six decades were 26.0 percent and 2.6 percent, respectively, in June 1983.

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities is a nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization and policy institute that conducts research and analysis on a range of government policies and programs. It is supported primarily by foundation grants.