Press Release: Setting The Right Fiscal Target: Policymakers Should Stabilize Debt As Share Of Economy Over Next Decade

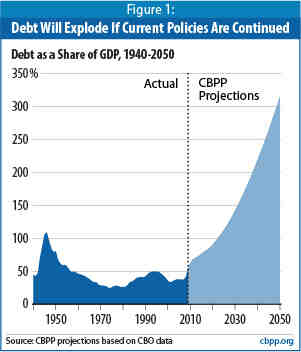

Deficits and debt will rise to unprecedented levels in coming decades without major changes in federal budget policies, so policymakers should set a goal of stabilizing the debt as a share of gross domestic product (GDP) over the next decade, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities reported today.

In its analysis, “The Right Target: Stabilize the Federal Debt,” the Center said that, to reach that goal, policymakers would have to trim projected deficits by more than half— to about 3 percent of GDP — by no later than 2019.

That would be no small achievement. To halve the deficit by 2019, policymakers would need to produce savings that are nearly twice as large as that of any prior deficit-reduction effort. And they would have to do so just as the baby boomers are retiring in large numbers (swelling the ranks of Social Security and Medicare beneficiaries) and health care costs are continuing to grow faster than the economy (driving up per-person costs for Medicare and Medicaid).

While policymakers should focus their attention as soon as possible on reducing the deficit, the report advises against actually having any large deficit-reduction measures take effect until the economy has sufficiently recovered from the recession and is strong enough to absorb them.

Pew-Peterson Target Overly Ambitious

A budget reform commission funded by the Pew Charitable Trust and the Peter G. Peterson Foundation recently called for policymakers to stabilize the debt-to-GDP ratio at 60 percent by 2018. While noting agreement with many of that commission’s conclusions about the long-term problem, the Center’s report characterized that particular goal as overly ambitious and unnecessary.

Reaching that target would require policymakers to cut deficits over the 2013-2018 period by almost $825 billion a year, on average. Setting such an ambitious target could actually impede progress.

“Trying to reduce the debt too much too soon could actually make it harder to enact important deficit reduction legislation,” said James Horney, the Center’s director of federal fiscal policy. “If the standard for success requires budget cuts and tax increases that are so big that they’re politically unacceptable, Congress is less likely to take serious action.”

Moreover, there is no evidence that a debt-to-GDP ratio of 60 percent represents a threshold above which the potential harm to the economy rises to an unacceptable level. The 60 percent target is an arbitrary one, the CBPP report noted.

Further Deficit-Reduction Actions Would Still Be Needed

Reducing the deficit to 3 percent of GDP by no later than 2019 (and preferably earlier), as the Center recommends, would stabilize the debt at just over 70 percent of GDP, meaning that the debt (and hence, interest payments on it) would no longer grow faster than the economy. This should reassure the nation’s creditors both at home and abroad of the United States’ ability to service its debt, and keep interest costs under control.

Given rising health care costs and demographic pressures, policymakers will almost certainly need to undertake further major rounds of deficit reduction to keep the deficit from rising above 3 percent of GDP in the decades after 2019, the Center noted. Policymakers also can determine then whether to seek to reduce the debt to a lower percentage of GDP.

Projections Show Debt Skyrocketing to Historic Levels in Coming Decades

Without policy changes, expenditures (other than interest payments on the national debt) will increase from 19.2 percent of GDP in 2008 to 24.5 percent in 2050, the Center projects. Revenues, meanwhile, will total only 18.2 percent of GDP in 2050, a little below their average of 18.4 percent over the last 30 years. The federal government ran deficits in all but four of those years, and revenues were nearly 20 percent of GDP or higher in each of the years that the budget was balanced.

Main Causes Are Rising Health Costs and Aging of Population

The two main sources of rising federal expenditures over the long run are rising per-person costs throughout the U.S. health care system — both public and private — and the aging of the population, the report explains. Together, these factors will drive up spending for the “big three” domestic programs: Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security. Growth in those programs accounts for all of the increase in federal program spending as a share of GDP over the next 40 years and beyond.

Total spending for all federal programs other than the “big three” — including all other entitlement programs — is projected to shrink as a share of the economy in coming decades, so these programs are not part of the long-term fiscal problem. Statements that we face a general “entitlement crisis” are, thus, mistaken.

Rising health costs exacerbate the long-term budget problem two ways. They increase federal spending by raising per-beneficiary costs in Medicare and Medicaid. Also, because of the tax preferences for employer-sponsored health coverage and certain other health care spending, rising health costs erode the tax base by increasing the share of income that is exempt from taxation.

Both the House- and Senate-passed health care bills take essential steps to begin constraining health cost growth while improving the quality of care system-wide, the report notes. (The Center’s projections do not reflect the budgetary impact of the proposed legislation.) The health reform bills provide for numerous studies and demonstration programs to test new approaches to providing health care. Information gleaned from these efforts should help lawmakers shape future legislation that they will need to enact in order to further slow the rate of growth of health care spending to an acceptable rate.

Tax Decisions Will Have Major Impact on Size of Problem

If current tax policies — such as the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts — are continued, revenues will remain well below the level needed to stabilize the debt-to-GDP ratio, the analysis warns.

Policymakers could shrink the fiscal problem through 2050 by two-fifths by allowing the tax cuts to expire as scheduled in 2010 or fully offsetting the cost of any tax cuts they choose to extend. The savings would start almost immediately (in 2011) and reduce projected interest payments on the debt by a larger amount each year. But, there is virtually no chance that policymakers will pay for all such tax-cut extensions, the Center notes, and even if they did, this alone wouldn’t place the nation on a sustainable long-term fiscal path.

Recession-Related Costs Not a Significant Cause of Long-Term Problem

Last year’s economic recovery act has added only very slightly to the long-run gap, the report explains, because all of its provisions are temporary. Temporary costs — even if very large in the short run — add little to the long-term fiscal problem, as opposed to permanent costs (such as the Medicare drug benefit or extending the tax cuts) because their costs are small relative to the total size of the economy over the long run.

Likewise, additional expenditures to support economic recovery of the magnitude that Congress is now considering would have only a tiny effect on the long-term picture.

The report is available here.

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities is a nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization and policy institute that conducts research and analysis on a range of government policies and programs. It is supported primarily by foundation grants.