WHY THE PRESIDENT'S SOCIAL SECURITY PLAN

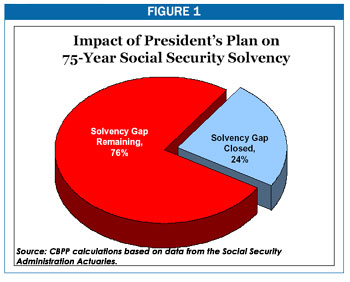

This week, a new Center analysis showed that the President’s Social Security plan as it now stands (the two main parts of which are private accounts and sliding-scale benefit reductions) would close just 30 percent of the total Social Security shortfall over the next 75 years, much less than is commonly thought. Additional benefit reductions, new revenues, or large transfers from the rest of the budget would be needed to keep Social Security solvent. Ordinarily, the kinds of estimates in the Center’s report would come from an analysis by the Social Security actuaries. It is standard practice for policymakers and outside analysts who present Social Security plans to request an analysis from the actuaries and then release it when they present their plans (or shortly thereafter). But since the White House has not released such an analysis, the Center’s report provides some of the standard actuarial and fiscal estimates of the President’s proposal — based on data from the actuaries — that are needed to evaluate the proposal properly. The private accounts would wipe out about half of the solvency gain over the next 75 years that would be achieved by the benefit reductions.

Under two other common measures of Social Security’s finances, the President’s plan would make the situation worse.

Many Low-Income Beneficiaries Would Not Be Protected Against Benefit Cuts Another Center report issued this week, based on a recent White House document, shows that many low-income Americans would be affected by the President’s sliding-scale benefit reductions. Those reductions do not apply to the retirement benefits of the lowest 30 percent of wage-earners, but they would apply to a substantial number of other low-income beneficiaries whose benefits are based on someone else’s earnings history. Examples include a child’s survivors benefit that is based on his deceased parent’s earnings, an elderly widow’s benefit that is based on her deceased husband’s earnings, and a divorced spouse’s benefit that is based on her ex-husband’s earnings. If, for example, the earnings of a deceased worker are not in the bottom 30 percent, the survivors benefits based on this worker’s earnings would be reduced under the President’s plan, regardless of the survivor’s income level. A document the White House released to reporters May 4 shows that under the President’s plan, benefits for the lowest-income 20 percent of beneficiaries aged 62 to 76 in 2050 would be reduced by an average of $528 a year. Moreover, this figure may understate the effect of the reductions, since it does not take into account the children, surviving parents, and widows over 76 whose benefits could be reduced. Roughly four million widows and two million children at all income levels receive Social Security benefits. Members of these groups, as well as divorced elderly spouses, can be particularly vulnerable to the effects of benefit reductions because in many cases, their incomes fall sharply after their divorce or the death of their parent or spouse.

|

By themselves, the President’s benefit reductions would close about 59

percent of the Social Security shortfall over the next 75 years. But the

private accounts would undo about half of that gain, primarily because of the

time lag between the diversion of funds into the private accounts (which would

occur throughout a worker’s career) and the reductions in Social Security

benefits to “pay for” that diversion (which would not occur until the worker’s

retirement).

By themselves, the President’s benefit reductions would close about 59

percent of the Social Security shortfall over the next 75 years. But the

private accounts would undo about half of that gain, primarily because of the

time lag between the diversion of funds into the private accounts (which would

occur throughout a worker’s career) and the reductions in Social Security

benefits to “pay for” that diversion (which would not occur until the worker’s

retirement).