|

EXPERTS AGREE THAT CAPITAL GAINS TAX CUTS LOSE REVENUE

During Wednesday’s Democratic presidential debate, Charles Gibson of ABC News made the following statements about capital gains taxes:

- “Bill Clinton in 1997 signed legislation that dropped the capital gains tax to 20 percent and George Bush has taken it down to 15 percent and in each instance when the rate dropped, revenues from the tax increased. The government took in more money.”

- “So why raise it [the capital gains rate] at all, especially given the fact that 100 million people in this country own stock and would be affected.”

These statements, echoed in a Wall Street Journal editorial today, are seriously misleading, as explained below.

Cutting capital gains rates reduces revenues over the long run. That’s the conclusion of the federal government’s official revenue-estimating agencies, as well as outside experts and the Bush Administration’s own Treasury Department.

- The non-partisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and the Joint Committee on Taxation have estimated that extending the capital gains tax cut enacted in 2003 would cost $100 billion over the next decade. The Administration’s Office of Management and Budget included a similar estimate in the President’s budget.

- After reviewing numerous studies of how investors respond to capital gains tax cuts, CBO commented that “the best estimates of taxpayers’ response to changes in the capital gains rate do not suggest a large revenue increase from additional realizations of capital gains — and certainly not an increase large enough to offset the losses from a lower rate.”

- The Bush Administration Treasury Department examined the economic effects of extending the capital gains and dividend tax cuts. Even under the Treasury’s most optimistic scenario about the economic effects of these tax cuts, the tax cuts would not generate anywhere close to enough added economic growth to pay for themselves — and would thus lose money.

While a capital gains tax cut can lead investors to rush to “cash in” their capital gains when the lower rate first takes effect, it does not raise revenue over the long run.

- Especially when a capital gains cut is temporary, like the 2003 tax cut that Gibson cited, investors have a strong incentive to sell stocks and other assets in order to realize their capital gains before the capital gains tax rate increases. This can cause a short-term increase in capital gains tax revenues, as happened after the 2003 tax cut.

- Capital gains revenues also increased after 2003 because the stock market went up. But the stock market increase was not a result of the 2003 tax cut, as a study by Federal Reserve economists found. European stocks, which did not benefit from the U.S. capital gains tax cut, performed as well as stocks in the U.S. market in the period following the tax cut.

- To raise revenue over the long run, capital gains tax cuts would need to have extraordinary huge, positive effects on saving, investment, and economic growth that virtually no respected expert or institution believes they have. In fact, experts are not even sure that the long-term economic effects of these capital gains tax cuts are positive rather then negative.

One reason is that preferential tax rates for capital gains encourage tax sheltering, by creating incentives for taxpayers to take often-convoluted steps to reclassify ordinary income as capital gains. This is economically unproductive and wastes resources. The Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center’s director Leonard Burman, one of the nation’s leading tax experts, has explained, “shelter investments are invariably lousy, unproductive ventures that would never exist but for tax benefits.” Burman has concluded that, “capital gains tax cuts are as likely to depress the economy as to stimulate it.”

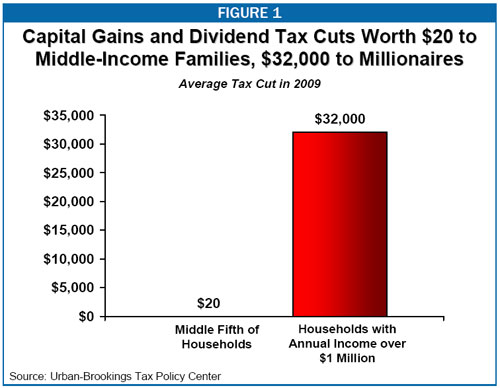

Middle-income families derive only a miniscule benefit from the 2003 cuts in capital gains and dividends.

Charles Gibson’s second statement — that 100 million Americans own stock and would be affected by a change in the capital gains tax rate — also is mistaken.

- Most middle-income Americans own much or all of their stock through 401(k)s, IRAs, or other tax-preferred saving accounts. They do not pay taxes when their stocks within those accounts go up, so a change in the tax rate doesn’t affect them.

-

Even among the minority of middle-class Americans who do benefit from the capital gains and dividend tax cuts, the benefits are very small. This is because capital gains and dividend income is highly concentrated at the very top of the income scale. The Tax Policy Center estimates that the highest-income 5 percent of U.S. households receive 83 percent of total capital gains income.

- According to the Tax Policy Center, the average household in the middle of the income spectrum received $20 from the 2003 capital gains and dividend tax cuts. The average household earning over $1 million received $32,000, or 1,600 times as much.

The myth that tax cuts pay for themselves hinders a debate on the nation’s budget priorities — and its serious long-term budget problems and the tough choices we must make to address them — by creating the illusion of a free lunch. Such free lunches do not exist. Capital gains tax cuts either make the nation’s daunting long-term budget problems even more severe or consume scarce resources (primarily to the benefit of the most well-off) that could otherwise be used for purposes such as moving toward universal health coverage or improving the educational system.

# # #

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities is a nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization and policy institute that conducts research and analysis on a range of government policies and programs. It is supported primarily by foundation grants. |