- Home

- Rainy Day Funds: Opportunities For Refor...

Rainy Day Funds: Opportunities for Reform

Summary

As states slowly emerge from the fiscal crisis, policymakers can evaluate how well their state reserve funds worked to cushion deficits during the downturn. This is an opportune time to strengthen state reserve policies and to begin to rebuild depleted state reserve funds.

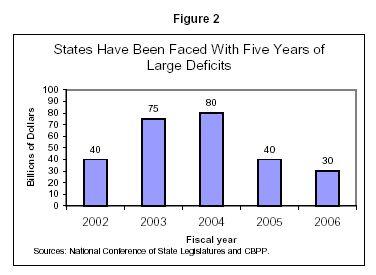

Since 2001, states have used about $30 billion in reserve funds — which includes both general fund balances and rainy day fund balances — to help close cumulative deficits of over $250 billion. In particular, states used reserves extensively to help close gaps in the early part of the fiscal crisis. Reserves closed about one-quarter of the deficits that developed through fiscal year 2003.

Arguably, states need to do an even better job of saving than they did in the 1990s. States entered the most recent downturn with reserves equivalent to 10.4 percent of a year’s expenditures, far more than they had on hand in either of the previous two downturns. Nevertheless, deficits during the downturn were five times the amount states had accumulated. A 1999 study by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities as well as recommendations from the Government Finance Officer’s Association suggests that an adequate level of total reserves is 15 percent of a year’s expenditures spending — or more.

The need to build stronger reserves argues for states beginning to rebuild those reserves as soon as possible. Many years are required to reach an adequate level of reserves.

Some states may not yet be ready to make deposits. Many states are still feeling the lingering effects of the fiscal crisis and the slow economic recovery. About half the states are working to close FY 2006 deficits of over $30 billion. While these states may not have the resources to begin rebuilding their financial reserves now, there are steps they can take in preparation for rebuilding. Policymakers have an opportunity to enact some critical policy changes to improve their reserve policies so that they are better prepared for the next fiscal crisis. These steps include the following.

- Create rainy day funds. Arkansas, Colorado, Illinois, Kansas and Montana do not have separate rainy day funds. These states should create separate funds dedicated to saving resources during good times to cushion the blow of a recession.

- Increase or remove rainy day fund caps. Rainy day fund caps place a limit on how large the fund can grow, typically measured as a percent of the budget. If rainy day funds are statutorily or constitutionally capped at an inadequate level, such as 10 percent of the budget or less, then states are going to have difficulty accumulating adequate reserve balances. The first step states could take to improve their rainy day funds is either to remove the cap — perhaps substituting targets for a fixed cap — or to increase it to a more adequate level such as 15 percent of the budget.

- Improve rainy day fund deposit rules. Most states place a low priority on saving by only depositing year-end surpluses into their rainy day funds. States could develop a process to integrate rainy day fund transfers into the budget as part of an overall reserve policy that places a high priority on saving.

- Eliminate onerous replenishment rules. Six states — Alabama, Florida, Missouri, New York, Rhode Island and South Carolina — and the District of Columbia have created rules that require rainy day funds, after they are used, to be quickly replenished even if economic conditions have not improved. These replenishment rules both create a disincentive for using the fund and place the rainy day fund in competition with other programs for scarce resources during an economic downturn. These replenishment rules can be removed.

- Remove limits on legitimate use. Some states have reduced the effectiveness of rainy day funds in addressing budget deficits by requiring a super-majority of legislators to release the fund or by placing an arbitrary limit on how much of the fund can be released at any one time. These restrictions can be repealed.

Reserve Funds Helped States During the Recent Fiscal Crisis

Since 2001 states have struggled to close cumulative deficits of over $250 billion. Roughly $30 billion in state reserve funds have been used to help close state budget deficits and prevent the need for additional spending cuts or tax increases.

While the $30 billion in drawn down reserve funds represents less than one-eighth of the total deficits states faced, the reserves were critically important during the early part of the fiscal crisis. States were able to use reserves to close the unexpected deficits — particularly mid-year deficits — that occurred in the first years of the fiscal crisis, giving states needed time to develop longer-term tax increase and spending reduction proposals. Reserves closed about one-quarter of the deficits that developed through fiscal year 2003.

The primary reason that reserve funds played an important role in balancing state budgets is that states did a better job of saving during the years leading up the fiscal crisis than they did in the years leading up to the previous economic downturn of the early 1990s. In fact, state balances stood at 10.4 percent of spending at the end of 2000. Prior to the last recession of the early 1990s, states had total balances of only 4.8 percent of expenditures.

States Need to Begin Re-Building Their Reserves

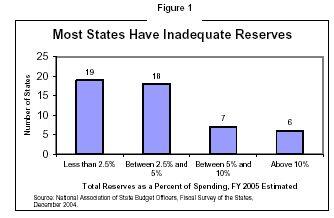

Overall, state reserves have declined from a twenty-year high of 10.4 percent of spending, $49 billion, at the end of FY 2000 to an estimated 3.3 percent of spending, $18 billion, at the end of FY 2005. Over 40 percent of these remaining reserves are concentrated in just five states — Alaska, Florida, Georgia, New York and Texas.[1]

Because states used a large portion of their reserves during the fiscal crisis, many states now have low reserve levels. Between 2000 and 2005, the number of states with reserves of 5 percent or more of spending declined from 39 to 13. Over the same period, the number of states with reserves of 10 percent or more spending declined from 23 to 6. (See Table 1 for state-by-state data on appropriated FY 2005 rainy day fund balances, general fund balances, total reserve balances, and total reserves as a percent of spending.)

States need to begin re-building reserves now, or as soon as possible. Building adequate reserves takes time, and the $50 billion reserves with which states entered the most recent downturn were accumulated over the full decade of economic prosperity. It is impossible to predict how long the growth segment of the current business cycle will last, but ten years was an usually long period of prosperity.

| Table 1 | ||||

| State | FY 2005 Appropriated Rainy Day Fund Balance | FY 2005 Appropriated General Fund Balance | FY 2005 Appropriated Total Reserves | FY 2005 Appropriated Total Reserves as a % of Spending |

| Alabama | 140 | 65 | 205 | 3.5% |

| Alaska | 2,059 | - | 2,059 | 88.3% |

| Arizona | 25 | 8 | 33 | 0.4% |

| Arkansas | - | - | - | 0.0% |

| California | - | 783 | 783 | 1.0% |

| Colorado | - | 246 | 246 | 4.1% |

| Connecticut | 286 | - | 286 | 2.2% |

| Delaware | 148 | 430 | 578 | 20.3% |

| Florida | 999 | 868 | 1,867 | 7.8% |

| Georgia | - | 1,145 | 1,145 | 7.0% |

| Hawaii | - | 292 | 292 | 7.1% |

| Idaho | 21 | 77 | 98 | 4.7% |

| Illinois | - | 458 | 458 | 2.0% |

| Indiana | 46 | 291 | 337 | 3.0% |

| Iowa | - | 88 | 88 | 2.0% |

| Kansas | - | 210 | 210 | 4.5% |

| Kentucky | 117 | - | 117 | 1.5% |

| Louisiana | - | - | - | 0.0% |

| Maine | - | 11 | 11 | 0.4% |

| Maryland | 520 | 87 | 607 | 5.4% |

| Massachusetts | 624 | 25 | 649 | 2.7% |

| Michigan | - | 1 | 1 | 0.0% |

| Minnesota | 631 | 1 | 632 | 4.4% |

| Mississippi | 43 | - | 43 | 1.2% |

| Missouri | 232 | 26 | 258 | 3.6% |

| Montana | - | 140 | 140 | 10.6% |

| Nebraska | 177 | 8 | 185 | 6.7% |

| Nevada | 1 | 160 | 161 | 6.3% |

| New Hampshire | 17 | (50) | (33) | -2.5% |

| New Jersey | 288 | 110 | 398 | 1.4% |

| New Mexico | - | 708 | 708 | 16.1% |

| New York | 794 | 333 | 1,127 | 2.6% |

| North Carolina | 267 | 16 | 283 | 1.8% |

| North Dakota | 9 | 109 | 118 | 13.0% |

| Ohio | 181 | 120 | 301 | 1.2% |

| Oklahoma | 209 | 232 | 441 | 9.3% |

| Oregon | - | 116 | 116 | 2.5% |

| Pennsylvania | 267 | 5 | 272 | 1.2% |

| Rhode Island | 90 | 1 | 91 | 3.1% |

| South Carolina | 75 | 149 | 224 | 4.4% |

| South Dakota | 139 | - | 139 | 14.1% |

| Tennessee | 275 | 1 | 276 | 3.0% |

| Texas | 458 | 728 | 1,186 | 4.0% |

| Utah | 67 | 3 | 70 | 1.8% |

| Vermont | 46 | - | 46 | 4.8% |

| Virginia | - | 31 | 31 | 0.2% |

| Washington | - | 465 | 465 | 3.9% |

| West Virginia | 85 | 11 | 96 | 2.9% |

| Wisconsin | - | 11 | 11 | 0.1% |

| Wyoming | 35 | 5 | 40 | 3.9% |

| Total | 9,371 | 8,524 | 17,895 | 3.3% |

| Source: National Association of State Budget Officers, Fiscal Survey of the States, December 2004. Note: Some NASBO rainy day fund and general fund balance figures have have been adjusted due to definitional issues and to match up with total reserve figures. Other differences from NASBO data are due to rounding. | ||||

Moreover, states may want to accumulate reserves that are greater than the 10.4 percent of spending with which they went into the recent fiscal crisis. The $250 billion in deficits over the period between 2002 and 2006 were five times larger than total reserves.

As states begin to emerge from the fiscal crisis and develop fiscal policies to deal with the next downturn the focal question is, how much saving is enough? In 1999, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities released an analysis that simulated a FY 2000-2003 recession. That analysis suggested that states on average would need reserves equal to 18 percent of spending to weather a simulated recession without substantially cutting spending or raising taxes. At the time — when many policymakers used a benchmark of five percent for an adequate reserve level — the estimates in the study seemed high to many state policymakers. However, given the severity of the current downturn, these previous estimates now appear quite conservative. [2]

The Government Finance Officers Association (GFOA) has also questioned the five percent reserve benchmark. In a statement of recommended practices released in 2002, GFOA stated that:

The adequacy of unreserved fund balance [which includes rainy day funds] in the general fund should be assessed based upon a government’s own specific circumstances. Nevertheless, GFOA recommends, at a minimum, that general-purpose governments, regardless of size, maintain unreserved fund balance in their general fund of no less than five to 15 percent of regular general fund operating revenues, or of no less than one to two months [that is, eight to 16 percent] of regular general fund operating expenditures. A government’s particular situation may require levels of unreserved fund balance in the general fund significantly in excess of these recommended minimum levels. [3] [italics added]

Clearly the experience of the last several years indicates that in the future states should plan on targeting the upper bound of GFOA’s recommendation — reserves of 15 percent of operating expenditures.

Building a rainy day fund of 15 percent of spending or more requires both strong reserve policies, to be discussed next, and sufficient time. If a state were set aside between 1.5 and 2.5 percent of revenue a year in a rainy day fund, it would take between 6 and 10 years to build a rainy day fund that equaled 15 percent of spending. If states wait too long to begin saving, they will likely not build adequate reserves before the next economic downturn begins.

Policies to Improve the Adequacy of Reserves

Many states are still feeling the effects of the fiscal crisis and the slow economic recovery. About half the states are working to close FY 2006 deficits that total over $30 billion. These states do not yet have the resources to begin re-building their financial reserves. Nevertheless, policymakers have an opportunity to enact some critical policy changes to improve their reserve policies so that they are better prepared for the next fiscal crisis.

The most important element of an effective reserve policy is a separate rainy day fund designed to accumulate funds during good economic times that can be used to address budget deficits during an economic downturn. Up to this point, this paper has focused on total state reserves which include both rainy day fund balances and general fund balances, because total state reserves provide the broadest measure of the resources available to help states weather fiscal difficulties. However, in many cases relying solely on general fund balances does not constitute an adequate reserve policy because there may not be rules governing the accumulation of the balances and there are often a number of other claims on the funds.

Currently, all but five states — Arkansas, Colorado, Illinois, Kansas and Montana — have some type of rainy day fund. Among these five states,

- Colorado has a four percent annual budget reserve requirement that does not function as a rainy day fund because the funds must be replenished each year. Colorado’s situation is complicated by a series of restrictive revenue and spending limits embedded in the constitution known collectively as TABOR (Taxpayers Bill of Rights) which make the development of a rainy day fund difficult because all revenue in excess of the limits is returned to taxpayers through rebates, tax credits and other mechanisms. Discussions are underway to reform TABOR and those discussions could include a mechanism for creating a rainy day fund.

- Illinois has a Budget Stabilization fund that does not serve as a rainy day fund because the entire fund must be paid back before the end of the fiscal year.

- Kansas has a five percent general fund balance requirement, but does not have a separate rainy day fund.

- Arkansas has a history of inadequate savings. In 2000, when total reserve balances were at their peak, Arkansas had no reserves.

- Montana has accumulated significant general fund reserves in the past, but does not have a separate rainy day fund.

Each of these states would benefit from a creating a well-designed rainy day fund. The features of a well-designed fund are described below. They include: a savings target at 15 percent of spending, appropriations to the rainy day fund in the annual budget, access to the funds during an economic downturn through a simple majority vote of the legislature, and rules that do not require the fund to be replenished before the economy has begun to recover.

Raise or Eliminate Caps

Rainy day fund caps place a limit on how large the fund can grow, typically measured as a percent of the budget. If rainy day funds are statutorily or constitutionally capped at an inadequate level, such as 10 percent of the budget or less, then states are going to have difficulty accumulating adequate reserve balances. While this may seem like an obvious point, this is the case in about 75 percent of the states with rainy day funds. Specifically, 35 states have capped their rainy day funds at 10 percent or less and 19 states have capped their rainy day funds at 5 percent or less of spending. These states are virtually guaranteed to find their rainy day funds inadequate. (See Table 2 which summarizes features of rainy day funds that states need to address.)

Rainy day fund caps clearly restricted rainy day fund growth during the 1990s. The rainy day funds in states with caps of five percent or less grew from an average of 1.0 percent of expenditures at the end of 1993 to only 3.7 percent of expenditures at the end of 2000. The rainy day funds in states without caps or with caps of 10 percent or greater grew from an average of 2.3 percent of expenditures at the end of 1993 to 9.0 percent of expenditure at the end of 2000. This indicates that raising rainy day fund caps is a critical policy option that states should pursue.

| Table 2 | ||||||

| State | No RDF | Cap of 10% or less | Deposit Rule | Replenishment Rule | Limit on Use | Super-Majority Requirement |

| Alabama | X | One-time funds | X | |||

| Alaska | See notes | X | ||||

| Arizona | X | See notes | X | |||

| Arkansas | X | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| California | Year-end Surplus | |||||

| Colorado | X | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Connecticut | X | Year-end Surplus | ||||

| Delaware | X | Year-end Surplus | X | |||

| District of Columbia | X | None | X | X | ||

| Florida | X | Year-end Surplus | X | |||

| Georgia | X | Year-end Surplus | X | |||

| Hawaii | Tobacco funds | X | ||||

| Idaho | X | See notes | X | |||

| Illinois | X | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Indiana | X | See notes | X | |||

| Iowa | X | None | ||||

| Kansas | X | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Kentucky | X | Year-end Surplus | ||||

| Louisiana | X | Year-end Surplus | X | X | ||

| Maine | X | Year-end Surplus | ||||

| Maryland | $50 million/year | |||||

| Massachusetts | Year-end Surplus | |||||

| Michigan | See notes | X | ||||

| Minnesota | X | Year-end Surplus | ||||

| Mississippi | X | Year-end Surplus | ||||

| Missouri | X | See notes | X | X | X | |

| Montana | X | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Nebraska | Year-end Surplus | |||||

| Nevada | X | Year-end Surplus | ||||

| New Hampshire | X | Year-end Surplus | ||||

| New Jersey | X | Year-end Surplus | ||||

| New Mexico | Year-end Surplus | |||||

| New York | X | Year-end Surplus | X | |||

| North Carolina | X | Year-end Surplus | ||||

| North Dakota | State bank profits | X | ||||

| Ohio | X | Year-end Surplus | ||||

| Oklahoma | X | Year-end Surplus | X | X | ||

| Oregon | X | Lottery revenue | X | X | ||

| Pennsylvania | Year-end Surplus | X | ||||

| Rhode Island | X | See notes | X | |||

| South Carolina | X | Year-end Surplus | X | |||

| South Dakota | X | Year-end Surplus | ||||

| Tennessee | X | See notes | X | |||

| Texas | X | Year-end Surplus | X | |||

| Utah | X | Year-end Surplus | ||||

| Vermont | X | Year-end Surplus | ||||

| Virginia | X | See notes | X | |||

| Washington | X | Year-end Surplus | X | |||

| West Virginia | X | Year-end Surplus | ||||

| Wisconsin | X | Year-end Surplus | ||||

| Wyoming | Year-end Surplus | |||||

| Total | 5 | 35 | Year-end Surplus=30 | 7 | 13 | 10 |

| Notes: NA - Not applicable because state does not have rainy day fund. Alaska: Mineral litigation settlements. Arizona and Michigan: Personal income growth formula determines amount to be transferred to the rainy day fund, legislature has discretion in determining actual transfer amount. Idaho: Automatic contribution when revenue growth exceeds 4%. Indiana: Automatic contribution based on personal income growth formula. Missouri: Required deposit when fund falls below required balanced. Rhode Island: 2% of revenue each year must be deposited, up to cap of 3% of revenue. Tennessee: Automatic appropriation based on 10% of revenue growth. Virginia: Automatic appropriation based on formula using prior six-years of revenue growth. | ||||||

The first step states should take to improve their rainy day funds is either remove the cap or increase it to a more adequate level, such as 15 percent of the budget. Even better, states could replace caps with target levels. For example, a state could set a target level for its rainy day fund of 15 percent of the budget. Once that target is met, policymakers could weigh their circumstances and options and decide whether to make additional deposits into the fund above the 15 percent level.

Improve Deposit Rules

The rules most states have set for contributions to rainy day funds do not give them much encouragement to save. The most common contribution rule — used in 30 out of 46 states with a rainy day fund — is that a portion of the state’s year-end surplus may be placed in the rainy day fund. [4] This rule has the advantage of ensuring that that the deposited funds are truly surplus, and that the state does not need the funds for some other purpose. The disadvantage is that the rainy day fund is last in line for receiving state resources.

For example, if a state is projecting a surplus during the period of budget deliberations, it may choose to increase expenditures or cut taxes; the rainy day fund would receive funding only if the actual surplus exceeds the projected surplus that already was allocated. This is largely what happened during the 1990s, when states increased spending modestly and cut taxes extensively when they enacted their budgets. In states with a year-end surplus deposit rule, rainy day fund deposits were made at the end of the fiscal year, long after the decisions to boost spending or cut taxes were made.

Other types of deposit rules can have the opposite effect; they may lead to required deposits when the state cannot afford to make them. Hawaii, Maryland, Missouri, and Rhode Island have rules that require annual contributions to their rainy day fund without regard to the state's fiscal conditions, which can lead to deposits being required during an economic downturn when the state is struggling to balance its budget.

Other states have rules intended to assure that rainy day fund contributions will be made when fiscal conditions are healthy. Seven states — Arizona, Florida, Idaho, Indiana, Michigan, Tennessee, and Virginia — use formulas based on growth in tax revenues or state economic growth to determine rainy day fund contributions.[5]

The rules in these seven states have both positive and negative aspects. On the positive side, in five of these seven states the deposit is made automatically at some point during the fiscal year. Unlike year-end surplus deposit rules, an automatic deposit assures that a deposit will be made.

But the rules in some of the seven states have other aspects that are less workable. In Florida, Idaho and Tennessee, the deposit formulas can require states to make contributions when state finances are not particularly strong. In Tennessee, for example, 10 percent of any revenue increase from one year to the next must be placed in the rainy day fund, which means that a deposit would be required even if revenue growth is modest.

In other states the formula tries to estimate whether there is sufficient economic growth to support a rainy day fund deposit. Arizona, Indiana and Michigan have formulas based on personal income growth. In Indiana, deposits must be made when personal income growth exceeds a particular standard. In Arizona and Michigan, the contribution calculation is used essentially as a guideline for determining the amount of rainy day fund contribution. In Virginia, the formula is based on comparing current revenue growth to the average growth rate in revenue collections over the previous six years.

There is now over two decades of experience during which states have experimented with different rules for rainy day deposits. Considering the range of outcomes of these experiments, it is possible to design a deposit rule that might better meet the needs of states. Such a rule would balance the competing needs of ensuring sufficient funding for public services while building an adequate reserve. The following suggests how this might be accomplished.

- During the budget development process, the state budget office could compare projected revenue (prior to any tax changes) to projected spending needs for the upcoming budget year. Ideally, the estimate of projected spending needs would utilize a baseline or current services approach that takes into account inflation, caseload increases, workload changes, and statutory requirements. Some states already prepare these types of estimates and include them in the proposed budget document, but many do not. However, most states that do not prepare a formal baseline projection should be able to produce an estimate of the required spending needs for the next fiscal year.

- If projected revenues exceed projected expenditure needs, a portion of that surplus (25 percent to 50 percent) could be appropriated as a transfer to the rainy day fund.

- Only the remaining portion of the surplus would be available for other uses. The actual transfer to the rainy day fund would occur at the end of the fiscal year, assuming revenues and spending hold to projections.

- A portion of any additional year-end surplus could also be deposited in the rainy day fund.

This process would ensure that all necessary spending needs are being met, that funds are being deposited into the rainy day fund and that funds are available to meet additional needs.

Policies to Ensure that Rainy Day Funds Can be Accessed When Needed

There are three types of policies that may result in states not being able to effectively tap rainy day funds when needed. They are replenishment rules, super-majority requirements and limits on use.

Eliminate Replenishment Rules

Six states — Alabama, Florida, Missouri, New York, Rhode Island and South Carolina — as well as the District of Columbia require that withdrawals from their rainy day fund be replenished over a specified period. Replenishment rules can be problematic for two reasons. First, in some cases they provide a disincentive to using the fund for fear funds will not be available to meet the replenishment requirements. Second, when replenishment must occur soon after the drawdown, rainy day deposits may compete with critical government programs and services for scarce resources during a time of fiscal strain.

Of the states that require replenishment of withdrawals from their rainy day funds, three — Alabama, Florida, and New York — allow replenishment to occur over a period of five years or more. This lengthy period helps increase the likelihood, although does not insure, that most of the replenishment will occur after the fiscal crisis is over. Historically, state fiscal crises have lasted two to three years. The current one, however, is entering its fifth fiscal year.

In Missouri and South Carolina, withdrawals from the rainy day fund are repaid over a three year period, in Rhode Island, the replenishment period is two years, and in the District of Columbia the fund must be paid back in one year. These onerous replenishment rules have created a barrier that has prevented these funds from being used for their intended purpose. Despite significant deficits throughout the fiscal crisis, the District of Columbia, Missouri and Rhode Island did not use their rainy day funds.

Remove Super-Majority Requirements

Ten states have super-majority requirements governing the release of rainy day fund resources to address budget deficits. [6] Super-majority rules create an unnecessary political hurdle to accessing the funds. These rules allow a minority of lawmakers to block the sensible use of rainy day funds in times of fiscal crisis.

Remove Limits on Use of Funds

Some 13 states set a limit on the amount of the rainy day fund that can be used at one time. These limits are a problem because they reduce the flexibility of state policymakers to address budget shortfalls in an effective manner. In addition, it may make sense for a state to use a large portion of the rainy day fund in the first year of the fiscal crisis because other budget balancing options, such as revenue increases or targeted budget cuts, may take more time to analyze and implement and are more appropriate for addressing the second or third year of the downturn.

In some cases these limits exist to minimize the use of the fund during periods of economic growth, a reasonable goal. But it is difficult to craft a restriction on the amount of funds that may be used that applies only to periods of growth and that does not also limit flexibility during a downturn. A better mechanism for ensuring that the funds are used for the intended purpose is to restrict the use of the funds to addressing a budget deficit. [7]

End Notes

[1] Alaska has a $2 billion rainy day fund, about 10 percent of the $18 billion total, due to its unique revenue structure that is heavily reliant on oil and gas revenue. New York and Texas are large states, which means that even though they have significant reserves in dollar terms, their reserve levels are at or below 4 percent of spending. Florida and Georgia were conservative in their use of reserve funds throughout the fiscal crisis. In addition, a portion of the remaining balance across all states was difficult to access during the fiscal crisis due to restrictions placed on the use of rainy day funds and general fund balance.

[2] Iris Lav and Alan Berube, When It Rains It Pours, March 11, 1999.

[3] http://www.gfoa.org/services/rp/budget.shtml#10 .

[4] The 46 states with a rainy day fund include DC.

[5] Florida has two rainy day funds — the Budget Stabilization Fund and the Working Capital Fund. The Budget Stabilization fund requires a deposit when revenues increase from one year to the next. The Working Capital fund deposit rule is based on the year-end surplus and is included in the count of states which deposit a portion of the year-end surplus.

[6] Alaska, Delaware, Hawaii, Louisiana, Missouri, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Texas and Washington.

[7] For example New Mexico’s rainy day fund statute indicates that the fund may be used: “In the event that the general fund revenues, including all transfers to the general fund authorized by law, are projected by the governor to be insufficient either to meet the level of appropriations authorized by law from the general fund for the current year or to meet the level of appropriations recommended in the budget and appropriations bill...for the next fiscal year, the balance in the tax stabilization reserve may be appropriated by the legislature up to the amount of the projected insufficiency for either or both fiscal years.”