- Home

- Food Assistance

- The Future Of SNAP

The Future of SNAP

Testimony of Stacy Dean, Vice President for Food Assistance Policy,

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities,

Before the House Agriculture’s Nutrition Subcommittee

Thank you for the opportunity to testify today. I am Stacy Dean, Vice President for Food Assistance Policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, an independent, non-profit, nonpartisan policy institute located here in Washington. The Center conducts research and analysis on a range of federal and state policy issues affecting low- and moderate-income families. The Center’s food assistance work focuses on improving the effectiveness of the major federal nutrition programs, including the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP). I have worked on SNAP policy and operations for more than 20 years. Much of my work is providing technical assistance to state officials and other stakeholders and researchers who wish to explore options and policy to improve SNAP’s program operations to more efficiently serve eligible households. The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities receives no government funding.

My testimony today is divided into two sections: 1) SNAP’s critical role in our country as a federal nutrition program; and 2) ideas for consideration to strengthen SNAP for the future.

SNAP’s Critical Role

I’ve testified several times recently about the critical role SNAP plays in our country. I’m going to quickly summarize here the most important points about SNAP’s successful features and results, in part because these themes were so successfully drawn out in the series of hearings before this committee on SNAP over the past two years and highlighted in the comprehensive report the Committee issued late last year.

SNAP is a highly effective anti-hunger program.SNAP is a highly effective anti-hunger program. Much of its success is due to its entitlement structure and its national benefit structure, which focus its benefits to the households with the lowest incomes available to purchase groceries and assists poor families to obtain adequate nutrition, regardless of where they live. As of last December, SNAP was helping 43 million low-income Americans to afford a nutritionally adequate diet by providing them with benefits on a debit card that can be used only to purchase food. On average, SNAP recipients receive about $1.40 per person per meal in food benefits.

-

SNAP has largely eliminated severe hunger and malnutrition in the United States. A team of Field Foundation-sponsored doctors examined hunger and malnutrition among poor children in the South, Appalachia, and other very poor areas in 1967 (before the Food Stamp Program, as SNAP was then named, was widespread in these areas) and again in the late 1970s — after the program had been instituted nationwide. These physicians found marked reductions over this period in serious nutrition-related problems among children and gave primary credit to the Food Stamp Program.[1] Findings such as this led Senator Robert Dole to describe the Food Stamp Program as the most important advance in U.S. social programs since Social Security.

- SNAP is targeted at need and reduces poverty. SNAP reaches more than 80 percent of eligible households, USDA estimates.[2] It delivers the largest benefits to those least able to afford an adequate diet; roughly 92 percent of benefits go to households with monthly incomes below the poverty line, and 57 percent go to households below half of the poverty line, or below $840 a month for a family of three in 2017.

These features help account for SNAP’s large anti-poverty impact. SNAP kept 8.4 million people out of poverty in 2014, including 3.8 million children, and made millions of others less poor, according to Census data using the Supplemental Poverty Measure (which counts SNAP and other non-cash benefits as income). SNAP also lifted 2.1 million children above half of the poverty line.[3]

- SNAP helps low-income households put food on the table. SNAP benefits reduce food insecurity (which occurs when households lack consistent access to nutritious food because of limited resources) among high-risk children by 20 percent and reduces fair or poor health (as reported by their parents) by 35 percent, one study found.[4] Another recent study found that participating in SNAP reduced households’ food insecurity by about five to ten percentage points and reduced “very low food security,” which occurs when one or more household members have to skip meals or otherwise eat less because they lack money, by about five to six percentage points.[5]

- SNAP improves long-term health and educational outcomes. Recent research comparing the long-term outcomes of individuals in different areas of the country when SNAP gradually expanded nationwide in the 1960s and early 1970s found that disadvantaged children who had access to food stamps in early childhood and whose mothers had access during their pregnancy had better health and educational outcomes as adults than children who didn’t have access to food stamps. Among other things, children with access to food stamps were less likely in adulthood to have stunted growth, be diagnosed with heart disease, or be obese. They also were more likely to graduate from high school.[6]

- SNAP is highly responsive to the economy. SNAP is the most responsive means-tested program to changes in poverty and unemployment during economic downturns. It expands to meet need and then shrinks when need recedes, most recently during and after the Great Recession of 2007-09. This automatic response not only eases hardship for people directly hit by a downturn but also boosts economic activity in communities across the country, thereby acting as an “automatic stabilizer” for the weak economy.

- SNAP supports work. SNAP is designed to both supplement the wages of low-income workers and support workers during temporary periods of unemployment. Most SNAP recipients who can work do. The number and share of households that have earnings while receiving SNAP has been on the rise. Among SNAP households with at least one working-age, non-disabled adult, more than half work while receiving SNAP — and more than 80 percent work in the year prior to or the year after receiving SNAP. The SNAP benefit formula is structured so that participants have a strong incentive to work longer hours or to search for better-paying jobs. SNAP benefits gradually decline as earnings rise, reducing the “benefit cliff” effect in SNAP. And, as I discuss in more detail below, SNAP provides a state option to all but eliminate any benefit cliff effects in SNAP.

- SNAP is efficient and effective. USDA and states take seriously their roles as stewards of public funds and emphasize program integrity throughout program operations. The authorizing committees have mandated in SNAP some of the most rigorous integrity standards and systems of any federal programs. States and USDA have achieved the highest program integrity levels for SNAP in recent years in terms of both the payment error rate and the percentage of SNAP benefits that are illegally exchanged for cash. States and USDA devote significant resources and take advantage of the most modern tools to pursue allegations of fraud and root it out when found.

-

SNAP’s national benefit structure is key to these successes. States have a high degree of flexibility in how they operate the program, but SNAP’s benefit levels and eligibility rules are largely uniform across the states. The national benefit structure was established under President Nixon after an initial effort to operate the program without such standards resulted in enormous disparities across states, with some states setting income limits as low as half the poverty line.

The national benefit structure ensures that poor families can obtain adequate nutrition, regardless of where they live. It also substantially reduces differences across the states in their overall financial support for poor children — a fact of special importance to southern states and rural areas, which have lower cash assistance benefits, higher poverty, and lower fiscal capacity.

I also believe that the federal and state agencies that oversee SNAP are committed to the program, its participants, and strive for continuous improvement. In part, the five year Farm Bill cycle helps to foster an atmosphere of continual self-evaluation, a healthy sense of external scrutiny, coupled with the opportunity to pursue improvements when needed. While the core design of SNAP is largely unchanged since its origin, USDA and states have worked to strengthen and modernize the program to reflect new opportunities as well as respond to emerging challenges. This Farm Bill will be no different and we look forward to the opportunity to work with the Committee on continuing to improve SNAP and to build upon its core strengths.

Farm Bill Ideas for Consideration

The focus of today’s hearing is on ways to build on the strengths of SNAP. Over the past two years, the Committee has undertaken a serious effort to learn about SNAP, including the people it serves, how the program operates at the state level, and opportunities for improving its effectiveness. This learning is reflected in the Committee’s report, which details the program’s strengths, including the ways in which SNAP’s basic structure contributes to its effectiveness. Given the findings of the report, it is appropriate for the Committee to consider future policy improvements recognizing that the program is working well and meeting its key goals.

The remainder of my testimony will focus on a set of policy improvements that could strengthen the program without undermining the key programmatic elements that make it effective today. These policy ideas are informed by the Committee’s hearings, academic research on the program, and our work with state officials, client advocate, and service provider groups, as well as our own research. The following is not a comprehensive or final list of the Center’s suggestions for the 2018 Farm Bill. Instead, it is meant provide an overview of some of the key areas we recommend that you consider.

Improving SNAP’s Basic Benefit

SNAP’s maximum benefit per person per meal is about $1.90 and the average benefit is about $1.40, reflecting that most households are expected to contribute a share of their own income to purchase food. SNAP expects families receiving benefits to spend 30 percent of their net income on food. Families with no net income receive the maximum benefit, which is tied to the cost of the Department of Agriculture’s Thrifty Food Plan (a diet plan intended to provide adequate nutrition at a minimal cost). For all other households, the monthly SNAP benefit equals the maximum benefit for that household size minus the household’s expected contribution.

Given the modest maximum and average benefit, SNAP delivers strong outcomes. In recent years, however, there has been increasing concern and growing evidence that SNAP’s basic benefit level is out of date and not sufficient to ensure that participating households can afford a healthy diet. This evidence includes research by leading academics:

- James P. Ziliak, a professor of economics at the University of Kentucky, makes the case that SNAP benefit levels are “based on increasingly outdated assumptions, including unreasonable expectations about households’ availability of time to prepare food, and need to be modernized…” The current Thrifty Food Plan assumes that households can spend close to two hours per day preparing food, while households typically spend 30 minutes to an hour a day preparing food. [7] In addition to this assumption, the current Thrifty Food Plan, in an effort to develop a very low cost plan, assumes that households will consume a diet that is far outside the norm for what Americans eat, including far more of certain types of food – such as dry beans and fluid milk – and far less of other foods, including items commonly consumed like cheese and chicken.

- Studies also show that households experience a range of adverse outcomes due to running out of food at the end of the SNAP benefit month. For example, one study found that the rate of hospital admissions for low blood sugar (which can occur when diabetics reduce their food intake) among low-income individuals in California was 27 percent higher in the last week of the month compared to the first, an increase not found among higher-income individuals — suggesting that exhausting food budgets contributes to these hospitalizations. (California distributes SNAP in the first days of the month.)[8] Studies have also found that participants consume fewer calories and that diet quality decreases towards the end of the month as households exhaust their benefits.[9]

- Economics professors Patricia M. Anderson and Kristin F. Butcher[10] in a paper we recently commissioned, found that boosting SNAP benefits would raise not only the amount that low-income households spend on groceries but also the nutritional quality of the food purchased. The authors estimated the impact of an increase in SNAP benefits of $30 per person per month – or the equivalent of just under $7 per person per week. (This amounts to a roughly 20 percent increase in the Thrifty Food Plan.) Based on food spending patterns of households with somewhat more resources, the researchers found that a $30 increase would result in about $19 per person per month more in food spending. (This is less than the SNAP benefit increase, even though SNAP can be spent only on food, because the added benefits would free up household income for other necessities such as utility bills or non-food groceries that SNAP doesn’t cover.) That increase in food spending, in turn, would raise consumption of more nutritious foods, notably, vegetables and certain healthy sources of protein (such as poultry and fish, and less fast food. The increased food spending would also reduce food insecurity among SNAP recipients.

Such a significant increase may not be feasible in the 2018 Farm Bill. Yet, evidence is mounting that SNAP’s benefit is insufficient for all families to meet their basic food needs with a healthy diet. This topic merits further discussion and consideration. SNAP’s core purpose is to meet low income households basic nutritional needs. If its benefit levels compromise the program’s ability to achieve that goal, then they must be reconsidered.

The Benefit Cliff

Some policymakers and service providers have raised concerns that programs that provide assistance for low-income families may discourage work if participants are worried that they will face a “cliff” where they lose their benefits all together if they take a job or increase their earnings above the program’s income limit. SNAP currently contains three features that result in a fairly minimal benefit cliff for households with income right at the upper end of SNAP’s income eligibility limit.

First, SNAP’s benefit formula, which targets benefits based on a household’s income and expenses, phases out benefits slowly with increased earnings and includes a 20 percent deduction for earned income to reflect the cost of work-related expenses and to function as a work incentive. As a result, for most households with each additional dollar of earnings the household’s SNAP benefits will decline by only 24 to 36 cents. Most SNAP households, as a result, will see an increase in their total income when their earnings go up modestly.

The program does, however, have a federal gross income limit at 130 percent of the federal poverty line, a rule that creates a small but meaningful benefit cliff or benefit loss for some households who might increase their earnings above that level. For example, a typical household of three with income at 120 percent of the poverty line would lose about $200 a month in SNAP benefits if it took a new job or got a raise that lifted its monthly income above the gross income limit (which at 130 percent of poverty is about $2,200 a month for a family of 3). This loss of SNAP would cancel out the higher earnings and the household would be no better off, and in some cases could be worse off.

Fortunately, states currently have an option to lift the gross income limit through “broad-based categorical eligibility”. More than 30 states have taken advantage of the option thereby allowing benefits to phase out gradually for all working households. Consider the previous example in a state that used the categorical eligibility option to adopt a higher gross income limit. The household’s SNAP benefit would drop by only about $60 to $90 a month, so the household would still be better off with the higher paying job. This state option to raise the gross income limit through broad-based categorical eligibility is the second protection in SNAP against a benefit cliff. Maintaining this option will allow more states to smooth SNAP’s phase out and eliminate the relatively modest benefit cliff.

The third protection against a benefit cliff is its structural guarantee to make food assistance available to every household that qualifies under program rules and applies for help. SNAP households that leave the program because they find a job or get a raise and no longer qualify can count on SNAP being available if they need help again later. Without this guarantee a household that loses its job might have to wait until funding became available to resume benefits — as occurs now with child care and other benefits that are constrained by funding limitations from serving all who are eligible. The fact that SNAP is an entitlement lowers the perceived risks of working, making it easier for low-income families to take a chance on a new job or promotion.

We plan to do some more detailed analysis on SNAP’s income phase out and resulting benefit cliff and will publish those findings shortly in order to help inform the Committee’s review of this issue.

Assessing SNAP’s Response to Individuals with Disabilities

SNAP provides needed food assistance to millions of people with disabilities. Over one in four SNAP participants, equivalent to over 11 million individuals in 2015, has a functional or work limitation or receives federal government disability benefits, according to CBPP analysis of data from the 2015 National Health Interview Survey. The program makes an important difference in the lives of these individuals. Yet, people with disabilities are more likely to live in poverty, endure material hardships, and experience food insecurity. Lower family income, higher disability-related expenses, and the challenges of providing needed assistance and care to disabled family members undermine the economic well-being of people with disabilities and their families. People with disabilities are at least twice as likely to live in poverty and struggle to put enough food on the table as people without disabilities. Disabling or chronic health conditions may be made worse by insufficient food or a low-quality diet.

The Center has a forthcoming analysis on the role SNAP plays for low income individuals with disabilities and how we might improve the program to better address their needs. At a minimum, this issue merits further study by the Committee and USDA to determine whether federal nutrition programs could be improved or implemented better to meet the needs of individuals with disabilities.

Maintaining and Improving Access to SNAP

SNAP is very successful in reaching eligible people. USDA estimates that some 83 percent of eligible individuals participate in the program. Working to ensure that eligible households continue to access the program remains a top priority. Despite this strong participation rate, there are groups who participate at lower rates. Low-income seniors are an example. And, we are concerned that vulnerable SNAP participants, such as pregnant women, infants, and toddlers may be missing out on important supplemental supports through WIC. We believe there are effective low- and no-cost efforts to make better connections between eligible people and federal nutrition benefits.

-

Increasing eligible senior enrollment in nutrition and health benefits. Many low-income seniors who are eligible for SNAP are also eligible for Medicare Savings Programs (MSPs), which defray Medicare premiums and/or cost-sharing charges for poor and some near-poor seniors not enrolled in the full Medicaid program. Similarly, many SNAP-eligible seniors are also eligible for the Low-Income Subsidy (LIS) for the Medicare Part D prescription drug benefit. But participation rates in these programs among eligible low-income seniors are very low — generally in the range of only 35 to 50 percent. Connecting eligible poor seniors to the available federal health and nutrition benefits for which they are already eligible would make a major dent in hardship for low-income seniors.

In addition to lack of knowledge among low-income seniors about their potential eligibility for both nutrition and health benefits, senior participation also is inhibited by unnecessarily duplicative and uncoordinated application procedures. These procedures also push up administrative costs. While these programs have similar eligibility rules, seniors typically must apply for them via three duplicative processes — through the Social Security Administration (SSA) for LIS, at their state Medicaid agency for the MSPs, and at their state SNAP agency for SNAP (although the last two can be combined, and if a senior applies first for MSP, he or she should be deemed automatically eligible for the LIS).

Eligible seniors who don’t enroll forgo significant financial assistance that could make a large positive effect in helping them make their ends meet.[11] Tackling low participation rates across programs would be more effective in helping low-income seniors make ends meet than working to improve SNAP participation rates alone.

While some of these issues are outside of the purview of the Agriculture Committee, the Farm Bill represents an opportunity to engage on improving services for low-income seniors. One suggestion would be to support innovative pilots that test using Social Security field offices in high-poverty neighborhoods to enroll low-income seniors and people with disabilities in a broad set of benefits. Interested local sites could test models in which a single process could facilitate enrollment in Social Security, LIS, MSP, and SNAP for struggling elderly and individuals with disabilities.

-

Ensuring SNAP’s infants and toddlers are connected to WIC. Nutrition assistance programs play an especially important role for young children, whose brains are rapidly developing. Unfortunately, young children are likelier to live in poor and food-insecure families than older children and are particularly vulnerable to the negative health effects associated with a lack of proper nutrition. Low-income pregnant and post-partum women, infants and children up to age 5 who participate in SNAP are also income eligible for the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC). WIC provides nutritious foods, nutrition education, breastfeeding support, and referrals to health care and social services to its participants. SNAP and WIC’s nutritional support lessens the impact of hardship in early childhood and improves health and economic stability into adulthood.

SNAP does an excellent job of reaching eligible children, but it is unclear how many of SNAP’s young children are connected to WIC. Our analysis of administrative and Census data suggests that many toddlers and preschoolers enrolled in SNAP are missing out on WIC, despite being eligible and despite the supplemental assistance WIC could provide and the positive long-term health outcomes of the WIC program. Given these programs’ proven benefits on the long-term health and economic outcomes of young children, more can be done at the state level to ensure successful cross enrollment in these two complementary nutrition programs. USDA could promote this connection, set an expectation that states connect eligible SNAP participants to WIC and measure states’ success with respect to connecting infants and toddlers to these two effective interventions. Setting an expectation that states will assist low-income infants and toddlers with available federal nutrition assistance and then measuring states against that expectation will elevate this issue and likely drive improved outcomes. An effort like this would not require new spending and would improve the delivery of federal nutrition programs to SNAP’s infants and toddlers.

Eligibility

In general, SNAP is available to all households that meet the federal income and asset rules. The amount that households receive is calibrated to their individual financial circumstances and their ability to purchase a basic diet. There are several groups, however, whose participation is further restricted based on their demographic or other circumstances. An example of one of those restrictions worthy of reconsideration is on individuals subject to the SNAP’s three-month time limit.

One SNAP’s harshest rules limits unemployed individuals aged 18 to 50 not living with children to three months of benefits in any 36-month period when they aren’t employed or in a work or training program for at least 20 hours a week.[12] Under the rule, implemented as part of the 1996 welfare law, states are not obligated to offer all individuals a work or training program slot, and most do not. SNAP recipients’ benefits are cut off after three months irrespective of whether they are searching diligently for a job or willing to participate in a qualifying work or job training program. As a result, this rule is a time limit on benefits and not a work requirement, as it is sometimes described.

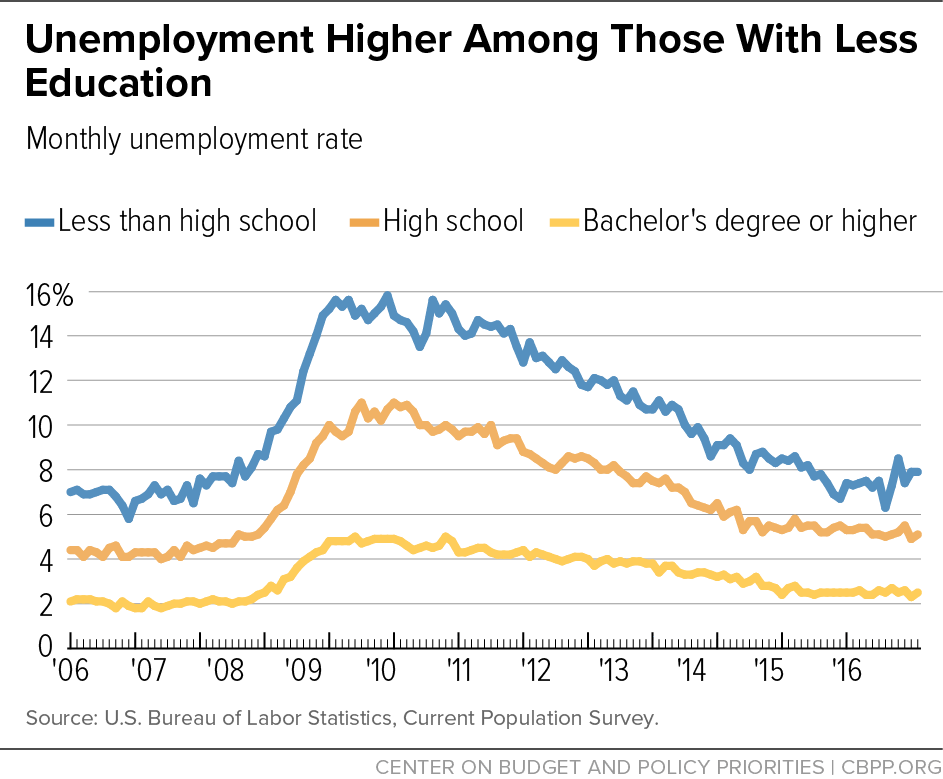

Many of the individuals subject to the time limit struggle to find employment even in normal economic times. Those subject to this rule are extremely poor, tend to have limited education, and sometimes face barriers to work such as a criminal justice history or racial discrimination. They also tend to have less education which is associated with higher unemployment rates. About a quarter have less than a high school education, and half have only a high school diploma or GED.[13] SNAP participants subject to the three-month cutoff are more likely than other SNAP participants to lack basic job skills like reading, writing, and basic mathematics, according to the Government Accountability Office (GAO).[14]

Unemployment rates for lower-skilled workers tend to be high. The unemployment rate for people lacking a high school diploma or GED — who make up about a quarter of all non-disabled childless adults on SNAP — stood at 7.5 percent in 2016, while the overall unemployment rate was 4.9 percent.[15] (See Figure 1.) Unemployment rates for workers in many lower-skilled occupations, such as those in the service industries, are also substantially higher than the overall unemployment rate. In December of 2015, unemployment in the food services industry was 6.9 percent, above the national overall average of 4.9 percent.[16]

While there have been few in-depth studies of those who are subject to the time limit, some evidence suggests that a sizable portion have a criminal history, which has a significant impact on job prospects. A detailed study of childless adults who were referred to community-based workfare in Franklin County (Columbus), Ohio found that about one-third had a felony conviction.[17] People with criminal records find it harder to be hired due to discrimination as well as low levels of education and poor work histories.[18] In addition to the stigma of incarceration, a number of states prohibit people with criminal histories from working in certain occupations. As a result, people with criminal backgrounds work less and have reduced earnings.

In addition to being harsh policy that punishes individuals who are willing to work, the rule is one of the most administratively complex and error-prone aspects of SNAP law. Many states also believe the rule undermines their efforts to design meaningful work requirements as the time limit imposes unrealistic dictates on the types of qualifying job training. For all of these reasons, many states and anti-hunger advocates have long sought the rule’s repeal.

The Senate versions of the 2002 and the 2008 Farm Bills included provisions that would have softened the limit by extending benefits to six months out of every 12 for these unemployed adults to better reflect the length of time they would typically avail themselves of the program in the absence of a time limit. And, that rule would be simpler for states to administer. Rep. Adams through HR. 1276, the Closing the Meal Gap Act of 2017, would convert the time limit to an actual work requirement by reframing the rule to say that that states cannot enforce the time limit unless they offer individuals subject to the rule a work slot or job training program that would meet the law’s strict standard. Both of these approaches would be meaningful improvements to the current situation which results in cutting off food assistance to individuals who are willing to work but unable to find 20 hours per week of employment.

Program Integrity and Oversight

The Farm Bill is an important opportunity to equip USDA and states with new tools to improve SNAP’s program integrity (which encompasses fraud and common error — the larger of the two issues). As new technology becomes available and as awareness improves of how problems arise, there are opportunities to improve SNAP accuracy and prevent fraud. And, with respect to fraud, while a relatively small problem, it’s an ever-changing concern. Criminals are adaptable, and the government’s response to them must also remain nimble and responsive to emerging patterns of fraud.

Often, our biggest obstacle to helping states implement new measures that would increase the accuracy of benefit issuance is cost. Modernized eligibility systems, access to useful third-party data, and the appropriate level of staff to process cases with a high degree of accuracy can be costly for states. While the federal government shares in the costs of administering the program, state budgets are the limiting factor to ensuring the best systems and technology are deployed throughout the program. Many states downsized their program operations during the recent recession and have not yet rebuilt the capacity necessary to take full advantage of new options and technology.

We offer the following suggestions as areas that Congress might want to consider to enhance SNAP’s program integrity.

- A joint federal-state effort to analyze client and retailer data for predictors of fraud and to share effective methods of identifying cases or stores that contain fraud or that are guilty of trafficking after a more in-depth investigation. Congress may wish to review whether USDA needs more resources or authority to remove offending stores from the program more quickly. In a hearing I participated in before the House Oversight Committee last year, one witness raised concerns that retailers that could be disqualified through a SNAP administrative process were not always removed from the program in a timely manner in order for law enforcement to build a more powerful criminal case against the store.

- Taking the National Accuracy Clearinghouse nationwide. Through an FNS pilot, several southeastern states and Lexis/Nexis are working to run checks across states for dual enrollment in SNAP. This pilot project appears to have been quite successful at identifying a small, but unacceptable, number of individuals enrolled in two states. We encourage you to discuss with FNS whether the Farm Bill could assist with rolling out the effort nationwide. Our only caveat would be that we want to be sure that states are required to disenroll clients when they report a move to another state. Our understanding is that some states are slow to take such action because they want evidence that the client is moving (which can be difficult to provide). Not being able to disenroll when moving can result in an unintended dual enrollment or a household being prevented from being able to enroll in SNAP in their new state because the originating state has not yet closed the household’s case.

- Some states pay (with the support of federal matching funds) a private company, Equifax, for access to employment and wage records for some SNAP households. Employers with large numbers of low-wage workers often prefer to have a third party handle inquiries regarding their employees’ wages and hours. State SNAP agencies report that when their case workers are able to easily access such current income information for applicants and participants, they have higher accuracy and less paperwork burden on both participants and employers. The Committee may wish to explore whether access to these private third-party data sources is something the program can and should provide to all states from the federal level. A single procurement might be a cost effective approach. The federal government, for example, now provides such data to state Medicaid programs through the federal data hub. Unfortunately that data is too old to be very useful to SNAP, which does a more current assessment of household circumstances. But the service HHS provides to states is worthy of replication in SNAP.

Employment and Training

SNAP’s existing employment and training (E&T) program allows states, within certain parameters, to design work and job training programs that help SNAP participants gain the skills, training or experience needed to gain regular employment. States can determine which populations and geographic locations to target for services and what types of employment services to offer. A number of states have been actively revising, expanding, and improving their E&T programs over the past few years.

As part of the 2013 Farm Bill, Congress authorized ten pilot projects to test, with a rigorous evaluation, whether SNAP E&T could more effectively connect unemployed and underemployed recipients to work. The selected pilots, announced in March 2015, include a mix of mandatory and voluntary E&T programs. Several of the pilots target individuals who face significant barriers to employment, including homeless adults, the long-term unemployed, individuals in the correctional system, and individuals with substance addiction. Many of the pilots involve multiple partners that help connect SNAP participants to resources and services that are available in the community and can help them prepare for, find, or retain employment. This includes partners that provide training, help recipients secure child care assistance and other supportive services, and assist job seekers identify job opportunities.

These pilots are intended to help both states and the federal government understand how SNAP E&T can most effectively help SNAP recipients connect to needed job-related services and which of those services the E&T program needs to provide itself to produce the best employment outcomes possible. In addition, the Farm Bill requires USDA to work with states to establish performance standards by which to assess E&T programs. Both of these initiatives are underway and are built upon USDA’s fairly robust effort over the past several years to support state efforts to improve their employment and training services, primarily by ensuring that their programs are preparing SNAP recipients for in-demand jobs, such as technical training and education-based programs. As a result of these policy initiatives, E&T is one of the most active areas of discussion, collaboration, and innovation within SNAP today.

We encourage the Committee to consider making new investments in E&T to expand job training opportunities for SNAP participants, perhaps through a competitive grant program. Such grants could be targeted to states with a proven track record producing positive employment outcomes in their E&T programs. Grants could support a wide range of programs including those targeted at removing barriers for individuals who face a difficult time finding employment such as ex-offenders or the homeless, providing case management services (a common theme in many of the pilots), or offering career and technical training informed by the local business community. The committee may also wish to consider proposals that would assist states that currently focus their E&T program primarily on job search and workfare — programs that have not been shown to be effective in improving employment outcomes for opportunity of participants — with the kinds of supports such as peer coaching and a learning collaborative that could help them to build more effective job training programs.

Assessing EBT

SNAP Electronic Benefits Transfer (EBT) is the electronic system that allows a recipient to authorize transfer of their government benefits from a Federal account to a retailer account to pay for the groceries they buy. EBT is used in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, and Guam. EBT has been fully implemented since June of 2004. As the system has been in place for more than ten years, this Farm Bill offers the opportunity to review how well the system is serving the program, whether it’s leveraging payment technology innovations, whether the reliability of the system matches commercial systems, and whether the costs of the EBT system are competitive with other similar technologies now available. One area of potential concern is the small number of vendors for SNAP EBT services and whether there is sufficient competition in the market for price and service. Today, only two vendors virtually hold all EBT contracts with states.

Issues External to SNAP for Consideration

Much of my testimony has been about how to improve or strengthen SNAP from within the program. It’s also useful to consider external factors that will set the context for what SNAP must respond to in the coming years.

The Labor Market

While reshaping SNAP’s employment and training program to be one that helps workers climb the economic ladder is a priority, no job training program can change the landscape of the low-wage labor market. As I mentioned earlier, the majority of working-age SNAP participants who can work, do work, but often the jobs they are working in, or are in-between, pay low wages, have variable, unpredictable schedules, don’t provide full-time hours to workers who want them, and don’t provide paid sick leave or other benefits. These workers often lack access to child care and other crucial job supports, and as a result of these conditions, these jobs tend to have high turnover. (For example, workers in jobs with paid sick leave are more likely to be able to stay employed in their current job than workers without, who may lose a job if they or a family member falls ill and they are unable to take the time off.[19])

SNAP participants who work are most likely to have service, sales, or office occupations, in occupations such as cooks, home health aides, janitors and maids, and personal care aides. They are most likely to work in the education and health industries (such as in schools, hospitals, home health services, and nursing homes), in retail trade (particularly in grocery stores and discount stores), and in leisure and hospitality (such as in restaurants and hotels).[20] These jobs tend to pay low wages and offer part-time and variable hours.

As a result, SNAP will continue to be an important support for low-wage workers and its features that respond and adapt to fluctuating earnings are important. It’s also important to note that many workers will experience periods of unemployment or underemployment due to the nature of the labor market and SNAP is a crucial support to them during that time.

Repealing the Affordable Care Act

While changes to the Affordable Care Act are still under consideration, it’s worth noting that the outcome of that debate will have an impact on SNAP. First, research has shown that medical expenses can affect food insecurity, as low-income individuals with health problems can face tradeoffs between food and medicine. For example, one study found that one in three people with chronic conditions were unable to afford food, adequate doses of medication, or both.[21] Another found that the probability of food insecurity increases as out-of-pocket medical expenses increase.[22] Legislation that reduces health coverage or increases out-of-pocket medical expenses for low-income individuals could have an impact on SNAP. Moreover, when individuals go without care they need, their health status may decline, making it more difficult to get and keep jobs – and making the job of E&T efforts that much more challenging.

In addition, SNAP is co-administered with Medicaid in most states. When there are significant changes to that program that require states’ attention, it can divert their focus from SNAP. Until the debate on health care concludes, it is premature to predict what the impact to SNAP will be and whether the Committee will need to respond. Nevertheless with changes as significant as those being contemplated by the House, there will surely be ripple effects to SNAP.

Downward Pressure on Non-Defense Discretionary Spending

Earlier this month, the Administration released its initial fiscal year 2018 budget proposal. The Administration’s budget outline now calls for cutting overall non-defense appropriations by another $54 billion below the full sequestration level. Under that proposal, the cumulative inflation-adjusted cut since 2010 would grow to 25 percent. For USDA, the Trump budget calls for cutting 2018 discretionary appropriations by $4.7 billion or 21 percent below 2017.

While the initial budget did not provide many details, this lower funding level raises concerns for SNAP. First, if FNS’s administrative budget is cut, that could mean reduced funding for USDA’s SNAP oversight, research, and program integrity initiatives. Second, the budget proposal did single out for elimination several programs outside USDA that also support SNAP households. The Low Income Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) provides low-income households with energy assistance and is slated for elimination under the Administration’s budget proposal. Many LIHEAP recipients also receive SNAP. If low-income families and seniors lose LIHEAP, it will make it more difficult for them to cover their basic utilities, raising concerns about the traditional trade-off in a struggling family’s budget between “heating and eating.” Similarly, cuts to rental assistance and other core forms of support to very low-income households will further strain their budgets and make it harder for them to afford life’s basics, including food.

Other proposed reductions, such as in the area of job training programs, also can have an impact on SNAP. First, many SNAP state agencies rely upon the job training and other services offered through the Workforce Investment Opportunity Act (WIOA) for at least some of their E&T training programs. Cuts to those programs will mean fewer work slots for E&T participants. And in many cases, the community-based organizations that provide SNAP job training are also working with Department of Labor funding. Cutting a core source of their funding may make their business less viable, reducing the overall pool of providers in a community that can provide job training. When the Administration’s more detailed budget is released in May, there may be many more proposed cuts that would impact SNAP participants or the program.

Chairman Conaway rightly described the Administration budget as a “proposal,” not policy. As the FY18 appropriations process moves forward however, current law funding for non-defense discretionary (NDD) programs continues to decrease relative to the FY10 level. Even if Congress does not adopt the additional cuts to NDD as proposed by the Administration, we can anticipate cuts to programs that will impact SNAP participants and the program.

Conclusion

SNAP is an efficient and effective program. It alleviates hunger and poverty and has positive impacts on the long-term outcomes of those who receive its benefits. And, SNAP has exacting standards with respect to eligibility determinations.

Over the many years that I have worked on this program, Congress and USDA have endeavored to balance the need to maintain SNAP’s successful structure and design with making changes to the program that respond to the needs of underserved groups such as working families and seniors, and test or implement new ideas to improve the program’s efficiency without compromising its effectiveness. As we look to the next Farm Bill, we look forward to working with you on changes that will improve the effectiveness of SNAP, rather than weaken or compromise its ability to meet the basic nutrition needs of struggling Americans. As you consider policy proposals, I urge you to keep that goal as your priority.

End Notes

[1] Nick Kotz, Hunger in America: The Federal Response (New York: Field Foundation, 1979).

[2] Kelsey Farson Gray and Karen Cunnyngham, “Trends in Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Participation Rates: Fiscal Years 2010 to 2014,” USDA, June 2016.

[3] CBPP analysis of 2014 Census Bureau data from the March Current Population Survey, SPM public use file; corrections for under-reporting from HHS/Urban Institute TRIM model. This is an update from a previous analysis published in a paper by Arloc Sherman and Danilo Trisi, “Safety Net More Effective Against Poverty Than Previously Thought,” CBPP, May 6, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/safety-net-more-effective-against-poverty-than-previously-thought.

[4] Brent Kreider et al., “Identifying the Effects of SNAP (Food Stamps) on Child Health Outcomes When Participation Is Endogenous and Misreported,” Journal of the American Statistical Association, 107(499), 2012: 958-975, http://batten.virginia.edu/sites/default/files/research/attachments/JASA_KPGJ_online(1).pdf.

[5] James Mabli et al., “Measuring the Effect of Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Participation on Food Security,” prepared by Mathematica Policy Research for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service, August 2013, https://www.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/Measuring2013.pdf.

[6] Hilary Hoynes, Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach, and Douglas Almond, “Long-Run Impacts of Childhood Access to the Safety Net,” American Economic Review, 106(4): 2016, 903–934.

[7] James Ziliak, “Modernizing SNAP Benefits,” Hamilton Project, Brookings Institution, May 2016, http://www.hamiltonproject.org/assets/files/ziliak_modernizing_snap_benefits.pdf.

[8] Hilary Seligman, et al., “Exhaustion of Food Budgets at Month's End and Hospital Admissions for Hypoglycemia,” Health Affairs, January 2014, 33(1):116-123, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4215698/.

[9] Jessica Todd, “Revisiting the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program cycle of food intake: Investigating heterogeneity, diet quality, and a large boost in benefit amounts,” Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy, 2014; Michael Kuhn, “Causes and Consequences of the Calorie Crunch,”, UKCPR Discussion Paper 2016-11, http://uknowledge.uky.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1109&context=ukcpr_papers; Jesse Shapiro, “Is there a Daily Discount Rate? Evidence from the Food Stamp Nutrition Cycle,” Journal of Public Economics, Volume 89, Issues 2-3, February 2005.

[10] Patricia Anderson and Kristin Butcher, “The Relationships Among SNAP Benefits, Grocery Spending, Diet Quality, and the Adequacy of Low-Income Families’ Resource” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 14, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/the-relationships-among-snap-benefits-grocery-spending-diet-quality-and-the.

[11] For example, the MSPs pick up annual Medicare Part B premiums of about $1,258 in 2016, as well as help with the Part B deductible of $166 and other co-insurance charges for those with incomes below the federal poverty line. SSA estimates that the Low Income Drug Subsidy, which pays for Medicare Part D premiums, deductibles, and co-payments, has an annual value of about $4,000 for those who are enrolled. USDA estimates that elderly individuals who are eligible for SNAP but not enrolled would qualify for more than $90 a month, or about $1,100 a year.

[12] For a more comprehensive discussion of the time limit rule, see: Ed Bolen et al., “More Than 500,000 Adults Will Lose SNAP Benefits in 2016 as Waivers Expire,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, updated March 18, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/more-than-500000-adults-will-lose-snap-benefits-in-2016-as-waivers-expire.

[13] Steven Carlson, Dorothy Rosenbaum, and Brynne Keith-Jennings, “Who Are the Low-Income Childless Adults Facing the Loss of SNAP in 2016?” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 8, 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/who-are-the-low-income-childless-adults-facing-the-loss-of-snap-in-2016.

[14] “Food Stamp Employment and Training Program,” United States General Accounting Office (GAO–3-388), March 2003, p. 17.

[15] Bureau of Labor Statistics.

[16] Industries at a Glance: Food Services and Drinking Places, Bureau of Labor Statistics, https://www.bls.gov/iag/tgs/iag722.htm.

[17] Ohio Association of Food Banks, “Franklin County Comprehensive Report on Able-Bodies Adults Without Dependents, 2014-2015,” October 14, 2015, http://admin.ohiofoodbanks.org/uploads/news/ABAWD_Report_2014-2015-v3.pdf.

[18] Maurice Emsellem and Jason Ziedenberg, “Strategies for Full Employment Through Reform of the Criminal Justice System,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, March 30, 2015, https://www.cbpp.org/research/full-employment/strategies-for-full-employment-through-reform-of-the-criminal-justice.

[19] Heather Hill. “Paid Sick Leave and Job Stability,” Work and Occupations, Vol.40 Issue 2, April 2013, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3825168/.

[20] Unpublished CBPP analysis of March 2016 Current Population Survey and 2015 American Community Survey data.

[21] Seth A. Berkowitz, Hilary K. Seligman, Niteesh K. Choudhry, “Treat or Eat: Food Insecurity, Cost-related Medication Underuse, and Unmet Needs,” American Journal of Medicine, 2014.

[22] Robert Hielsen, Steven Garasky, and Swarn Chatterjee, “Food Insecurity and Out-of-Pocket Medical Expenditures: Competing Basic Needs?” Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, Vol. 39, No. 2, December 2010, pp. 137-151.

More from the Authors