- Home

- Commentary: House Committee Misses Oppor...

Commentary: House Committee Misses Opportunity to Improve TANF

The 20th anniversary of Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) this year is an opportune time to improve the program, but the four bills the House Ways and Means Committee passed this week don’t address TANF’s key weaknesses.

One bill, the Social Impact Partnerships to Pay for Results Act, would set a dangerous precedent of raiding federal TANF funds to pay for projects unrelated to TANF’s goals. It would take $100 million from the TANF Contingency Fund to establish “social impact partnerships,” where private investors and philanthropic groups pay to implement social programs and other undefined initiatives and are repaid if the programs meet specific goals. Committee members of both parties expressed support for testing the concept, but the Republican majority rejected an amendment requiring that half of the funds be targeted to projects that improve children’s lives, even though the funds would come from a program targeted to poor families with children.

The TANF block grant has eroded substantially due to inflation and is worth 33 percent less than it was 20 years ago. The TANF block grant has eroded substantially due to inflation and is worth 33 percent less than it was 20 years ago. If anything, we should be adding money to TANF to restore its lost value, not siphoning off funding for projects that may never touch the lives of poor families with children.

A second bill, the TANF Accountability and Integrity Improvement Act, would explicitly permit states that have withdrawn state funds from their TANF programs to continue doing so rather than fix the problem. As a condition of receiving federal TANF funds, a state must meet a “maintenance-of-effort” (MOE) requirement by spending at least 80 percent of what it spent on TANF’s predecessor, Aid to Families with Dependent Children, just before TANF’s creation. (In some cases this requirement can be reduced to 75 percent.) For the last decade, though, some states have been withdrawing state spending on poor families with children and instead counting spending by non-profit organizations (such as food banks or domestic violence shelters serving TANF-eligible families) toward the state’s MOE contribution. The result is fewer services for poor families due to the cut in state funding.

Last summer, committee members of both parties agreed that states should no longer be allowed to count third-party spending, and the original bill to be considered by the committee phased out this type of spending over two years. At this week’s hearing, however, this bill was replaced by a substitute that simply freezes third-party MOE at current levels, essentially allowing states to continue the practice indefinitely.

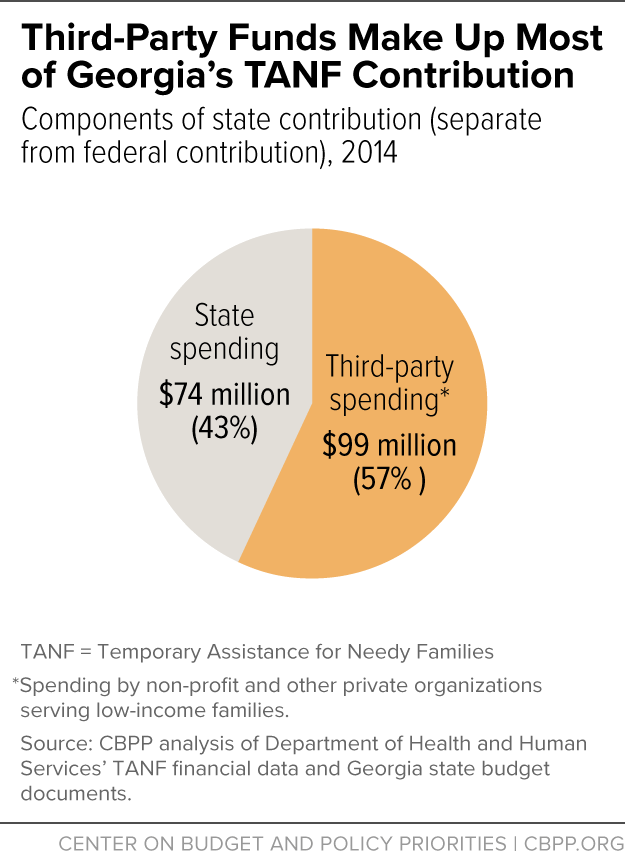

Georgia provides an example of how egregious this practice is. In 2014, Georgia met its MOE contribution of $173 million by spending about $74 million in state funds and counting $99 million in third-party spending from organizations like the Boys and Girls Club (see Figure 1).[1] This means Georgia spent just 32 percent of what it had spent on poor families with children before TANF’s creation.

Representative Tom Price’s (R-GA) defense of this practice — that faith-based and non-profit organizations do important work in their communities — misses the central point: when TANF was created, states agreed to continue paying their share of helping poor families with children escape poverty through work and providing a safety net for families unable to work. Eighteen states count third-party funds toward their MOE contribution; Georgia does so on the largest scale, but six other states (Alabama, Arizona, Missouri, New Hampshire, South Carolina, and Oregon) use third-party funds for more than 15 percent of their MOE requirement.[2] Despite its misleading name, the Ways and Means bill would allow states to continue this harmful practice.

On a more positive note, the third bill, the Accelerating Individuals into the Workforce Act, would create a subsidized jobs program for TANF recipients and noncustodial parents. It would use $100 million of the TANF Contingency Fund to test the effectiveness of wage subsidies in getting low-income parents into sustainable employment. States quickly scaled up subsidized jobs programs during the economic downturn with funds from the TANF Emergency Fund, creating more than 260,000 jobs.[3] But more experimentation is needed, especially for people with the most serious employment barriers, to understand how best to use subsidized jobs as an anti-poverty tool.

The last bill, the Reducing Poverty through Employment Act, would add a fifth purpose to the TANF program: reducing poverty by increasing employment entry, retention, and advancement. Unfortunately, the subsidized employment bill is the only one of the bills approved this week that would do anything to further that purpose (or any of TANF’s other purposes: assisting needy families with children; promoting job preparation, work and marriage; reducing out-of-wedlock pregnancies; and encouraging two-parent families).

If the committee is serious about improving TANF for the next 20 years — making it a stronger safety net that provides work opportunities and supports to families on their path to self-sufficiency — it should:

- Require states to spend more of their federal and state TANF dollars on TANF’s core purposes, including programs to prepare recipients for work and child care to support them while they work.

- Remove the restrictions that discourage states from placing TANF recipients in education and training programs that will prepare them for better jobs.

- Encourage states to develop employment pathways for individuals with the most significant employment barriers.

- Hold states accountable for getting TANF recipients employed.

- Hold states accountable for assisting families that are unable to work or find work.

TANF Cash Assistance Should Reach Millions More Families to Lessen Hardship

Increases in TANF Cash Benefit Levels Are Critical to Help Families Meet Rising Costs

Policy Basics

Income Security

End Notes

[1] CBPP analysis of Department of Health and Human Services’ TANF financial data and Georgia state budget documents.

[2] Kay Brown, “Temporary Assistance for Needy Families: Update on States Counting Third-Party Expenditures toward Maintenance of Effort Requirements,” Government Accountability Office, February 2016, http://www.gao.gov/assets/680/675110.pdf.

[3] LaDonna Pavetti, Liz Schott, and Elizabeth Lower-Basch, “Creating Subsidized Employment Opportunities for Low-Income Parents: The Legacy of the TANF Emergency Fund,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and Center for Law and Social Policy, February 16, 2011, https://www.cbpp.org/research/creating-subsidized-employment-opportunities-for-low-income-parents.

More from the Authors