- Home

- Commentary: The EITC Works Very Well – B...

Commentary: The EITC Works Very Well – But It’s Not a Safety Net by Itself

House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan’s recent report on safety net programs rightly praised the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) for reducing poverty and promoting work. But, Ryan’s report criticizes much of the rest of the safety net. And, over the past several years, Chairman Ryan’s budget plans have targeted low-income programs such as SNAP (formerly food stamps) and Medicaid for extremely deep cuts. While it’s heartening to hear Chairman Ryan trumpet the EITC’s success, policymakers need to understand that the EITC alone can’t do what’s needed to ameliorate poverty and hardship.

The EITC serves a specific role in our safety net: easing the taxes and supplementing the wages of low-income working families. It promotes work by providing the most help to families with significant earnings. A single parent with two children, for example, must earn between $13,650 and $17,850 in 2014 to qualify for the maximum credit. Those earnings are modest, to be sure, but most people in this earnings range work most of the year and work at least 30 hours per week when they have a job. In short, they have significant attachment to the labor force.

Here’s what the EITC (and its sibling the Child Tax Credit or CTC, which helps offset the cost of raising children) are not designed to do — and cannot do without other safety net programs:

- Help people who are out of work or can’t work. The EITC and CTC are designed to help families with at least modest earnings. But, some people don’t have jobs, particularly in a weak economy, or have long periods of unemployment during a year. Others can’t work due to illness or disability or the need to care for an ill or disabled child. Still others can’t work because they have young children and can’t earn enough to afford child care.

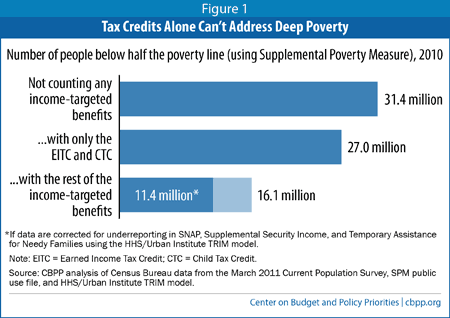

Without programs such as SNAP, Supplemental Security Income (SSI), and Medicaid, people in these families, including millions of children, couldn’t put food on the table, keep a roof over their head, and get needed health care. Helping them isn’t only the right thing to do — it’s also an investment in children. Research shows that basic assistance to children not only reduces short-term hardship but also improves their academic performance and long-term prospects. And, Medicaid coverage enables children to receive preventive care as well as treatment for everything from ear infections to cancer. - Keep people out of “deep poverty.” Because the EITC and CTC aren’t targeted to the very poorest families, they don’t do much to keep people out of deep poverty, or above half the poverty line. Overall, the EITC and CTC plus other programs targeted on low-income individuals — such as SNAP, SSI, and Temporary Assistance for Needy Families — kept an estimated 15 to 20 million people above halfthe poverty line (about $11,000 for a family of three) in 2010. (That estimate is based on the federal Supplemental Poverty Measure, which most analysts favor. The upper end of the range reflects estimates based on Urban Institute data that correct for the underreporting of government benefits.) Roughly 70 to 80 percent of these people would have remained in deep poverty if the EITC and CTC were the only forms of income-tested assistance for very poor families (see Figure 1).

- Help families get health care. The average EITC benefit for families with children was $2,254 in 2011 — not enough to buy health insurance for a family or pay health care bills when someone gets sick or needs expensive medications. The programs designed to help low-income people get decent health care are Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, and subsidies to buy private coverage through health reform’s new marketplaces, not the EITC.

- Help families on a monthly basis. Recipients get their EITC and CTC for the year in one lump sum when they file their income tax return. That works fine for many working families, helping them save for larger expenses and budget for the coming year, but poorer families and families whose incomes drop sharply due to a mid-year job loss need help during the year. And, for families that need significant help with large monthly expenses — such as putting groceries on the table and paying high rent or child care costs — monthly assistance programs are often a better fit. If a new mother needs help paying for child care to go back to work, for example, a tax credit that she needs earnings to qualify for and doesn’t arrive until she files her tax return the following winter or spring isn’t going to help her get back to work.

- Serve as an automatic stabilizer for the economy in recessions. Programs like unemployment insurance, SNAP, and Medicaid automatically expand during recessions when more people lose their jobs and need help. Since the EITC only goes to people who work, in contrast, it doesn’t help those who are out of work throughout the year. And, for people who still have earnings but whose earnings shrink during a downturn, the EITC rises for some, but falls for others. A recent study found that the EITC is only weakly counter-cyclical — that is, it expands only a small amount overall when unemployment rises.[1] For single-parent families, the largest group of EITC recipients, the study found “no evidence that the EITC stabilizes income” overall as unemployment rises. By contrast, other programs such as unemployment insurance and SNAP are far more responsive to increases in unemployment, according to the study.

The bottom line? The EITC is a critically important and highly effective part of the safety net, but it can’t — and wasn’t meant to — stand alone as our answer to poverty.

End Notes

[1] Marianne Bitler, Hilary Hoynes, and Elira Kuka, “Do In-Work Tax Credits Serve as a Safety Net?” National Bureau of Economic Research, January 2014, http://www.nber.org/papers/w19785.

More from the Authors