The “Mid-Session Review” that the Office of Management and Budget issued last month projects that revenues will be slightly above their 30-year average in 2007, measured as a share of the economy. The Administration and many of its supporters have cited this fact as evidence that current tax policies are generating an appropriate level of revenue and the Administration’s tax cuts therefore should be made permanent without the costs being offset. Similarly, Senator Charles Grassley, the ranking Republican on the Senate Finance Committee, has cited this fact as a reason for repealing the Alternative Minimum Tax without offsetting the large costs involved.

The simple fact that the government collected a particular level of revenue in the past says little, however, about what level of revenues is appropriate today, will be appropriate or necessary in the future, or even was appropriate in the past.

The government collects taxes to finance the services it provides, from national defense and law enforcement to Social Security and Medicare benefits for the elderly to investment in scientific and medical research, education, and environmental conservation. Although the government can borrow substantial sums for a time, it cannot borrow large amounts of money indefinitely.

The most meaningful standard for judging whether a particular level of revenue is appropriate thus is whether it provides adequate funding to support the public services that the nation judges to be worth paying for. As this analysis demonstrates, revenues at the historical average failed to meet this standard in the past, resulting in a long string of deficits, fail to meet this standard today, and will fail spectacularly to meet this standard in the future as rising health costs and the aging of the population place large additional demands on the public sector. Recently, David Walker, the Comptroller General of the United States, stated flatly in Congressional testimony that the fiscal challenges that lie ahead will necessitate raising revenues above the historical average.

A quick look at the nation’s finances over the past 30 years reveals a persistent mismatch between historical revenue levels and the funding needed for crucial public services.

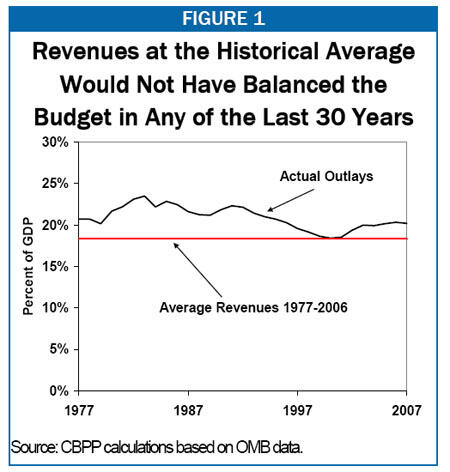

- Revenues at the 30-year average of 18.3 percent of GDP would not have balanced the budget in any of the last 30 years. (See Figure 1.)

- The only balanced budgets over this period occurred during the years from 1998 through 2001, all years in which revenues were markedly above the 30-year average.

- As a result of these persistent mismatches between outlays and revenues over the past 30 years, the government ran deficits over the period that averaged 2.6 percent of GDP.

- Today, OMB projects that even though federal spending is modestly below its 30-year average of 20.9 percent of GDP, revenues slightly above the historical average will still leave a deficit in 2007 of 1.5 percent of GDP, or $205 billion.

- Both parties have controlled Congress or the Presidency at various times over the past 30 years, and the years 2002-2006 saw unified Republican control of both Houses of Congress and the White House. Federal spending was higher than 18.3 percent of GDP in all of these years. Apparently, political leaders of both parties concluded that meeting the nation’s priorities required spending above the historical average level of revenues.

All of this was over a period in which health care costs in both the private and public sectors were lower than they are today and sharply lower than they will be in the future, primarily because of ongoing medical advances that improve health but increase health care costs. In addition, the share of the population that is elderly was lower over most of the past 30 years than it is today, and that share will increase markedly in coming decades. These developments will substantially increase the cost of supporting Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security in the years ahead.

Given these trends, if the historical level of revenues did not prove adequate over the past three decades, there is no way that it will prove adequate in the future. This is why the Comptroller General told the House Budget Committee on July 25 that meeting the fiscal challenges that lie ahead will necessitate raising revenues above the historical average as a share of GDP.[1]

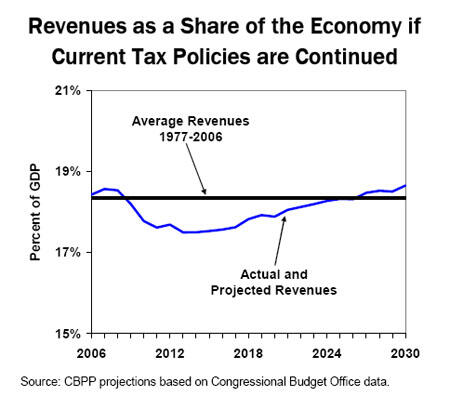

The fact that current tax policies are generating revenues at or above the historical average does not mean the same tax policies will continue to do so in the future. Projections from the Congressional Budget Office indicate that if current tax policies are continued — that is, if the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts are made permanent and relief from the Alternative Minimum Tax is continued, and none of these actions are offset by increasing other sources of revenue — revenues as a share of the economy will decline from 18.6 percent of GDP in 2007 to 17.6 percent of GDP in 2017, substantially below the historical average. [a] (See figure below.)

CBO projects that revenues will rise modestly after that as a share of the economy, largely as a result of ongoing real growth in individual incomes.[b] Nevertheless, if current tax policies are continued, it will take until 2027, or 20 years from now, just for revenues to return to their average level over the 1977-2006 period.

[a] The projected decline likely reflects a judgment by CBO that certain factors contributing to the increase in revenues as a share of the economy since 2004, like unusually strong corporate profits and above-normal levels of capital gains realizations, are temporary and will recede in coming years. The decline also reflects the continued phase-in of provisions of the 2001 tax cut, including estate tax repeal and repeal of a pair of income tax provisions commonly known as Pease and PEP.

[b] Growth in individual incomes increases the level of revenue as a share of the economy because the federal tax system is progressive; that is, people with higher incomes pay tax at higher rates. As a result, as economic growth raises real incomes, it also slightly increases the percentage of total income that is paid in taxes. (Individuals still experience significant increases in their real after-tax incomes as a result of economic growth.)

The plain truth is that even if major reforms are instituted in the U.S. health care system that slow growth in Medicare, Medicaid, and private-sector health care costs, and Social Security is reformed to restore long-term solvency to that program, the costs for these programs still will rise significantly (although by a smaller amount than would otherwise be the case). Advances in medicine and the aging of the population make that inevitable. If revenues remain at their past average of 18.3 percent of GDP, the result thus will be either crushing deficits and debt that could seriously injure the U.S. economy or draconian cuts in Medicare, Medicaid, Social Security, and other programs that the public almost certainly would not accept and that, if actually instituted, would subject tens of millions of Americans who are elderly, have disabilities, or are poor to hardship and place essential functions such as education, medical research, and infrastructure investment at risk.

The alternative is to restore fiscal sustainability through a balanced mix of reforms to the U.S. health care system, spending reductions, and revenue increases. Some have argued that inclusion of revenue increases in the mix would impose large costs on the U.S. economy. In fact, mainstream economists have generally found that the economic costs of restoring fiscal sustainability through such policies would be modest.

Indeed, the economic costs of restoring fiscal stability in this manner would pale in comparison to the economic costs of failing to bring the nation’s fiscal house in order. In response to questions posed by Senate Budget Committee ranking Member Judd Gregg about the effects of closing the long-term fiscal gap entirely through tax increases, the Congressional Budget Office recently explained:

Differences in the economic effects of alternative policies to achieve a sustainable budget in the long run are generally modest in comparison to the costs of allowing deficits to grow to unsustainable levels. In particular, the difference between acting to address projected deficits (by either reducing spending or raising revenues) and failing to do so is generally much larger than the implications of taking one approach to reducing the deficit [i.e., raising taxes or cutting spending] compared with another.[2]

Maintaining Revenues at Historical Levels Would Require Either Massive Deficits or Abandoning Commitments to the Elderly, the Poor, and Others

Health care costs are rising considerably faster than the U.S. economy is growing and are expected to continue doing so. Similarly, the elderly are projected to increase from 12 percent of the U.S. population today to 21 percent by 2050. These trends will substantially increase the cost of Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security as a share of the economy in the years ahead.

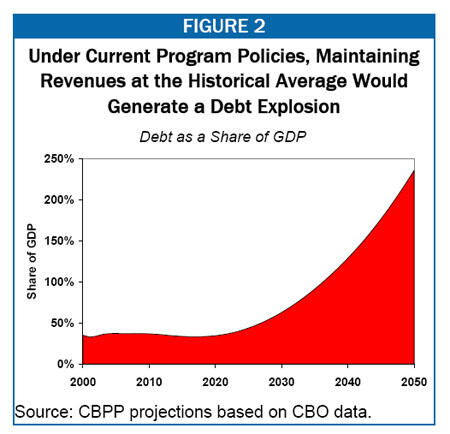

If revenues remain at their historical average and current program policies are maintained, these changes will cause the mismatch between the government’s revenues and its obligations to explode. Deficits would reach approximately 21 percent of GDP by 2050, and the debt would reach more than 200 percent of GDP, more than twice the highest level it reached at any prior point in the nation’s history.[3] (See Figure 2.)

Deficits and debt of this magnitude are widely regarded as posing serious risk to the economy. CBO has stated that mounting deficits would “eventually cause a persistent decline in economic growth and the standards of living in the United States.” [4]

There is broad consensus that this grim scenario cannot be allowed to come to pass. Avoiding it will require difficult choices, including reductions in projected spending, particularly in the health care area. But it will be virtually impossible to slow health costs so dramatically that Medicare and Medicaid costs do not continue rising somewhat faster than the economy for a very long time. Despite inefficiencies in the U.S. health care system, the growth in health care costs is driven to a large extent by medical advances that can improve health and lengthen life.

Historical experience suggests that the overall health benefits of these medical advances are likely to justify most or all of their costs. Noted Harvard health economist David Cutler has calculated that the health improvements that have resulted just from advances in neonatal care and the treatment of heart disease were sufficient to justify all of the increase in health care spending that occurred in the United States between 1950 and 1990.[5]

It is hard to believe Americans will not seek to avail themselves of the medical breakthroughs that will occur in the years and decades ahead. As a result, health care cost growth is expected to continue even in the unlikely event that nearly all inefficiencies in the U.S. health care system were eliminated, a step that would require a highly controversial restructuring of a sector that comprises one-sixth of the U.S. economy.

Moreover, the growth in the elderly population will itself result in significant growth in Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid costs. In short, even if policymakers are able to identify and enact sensible savings in the health care system and Social Security, the costs of these programs will continue to increase substantially as a share of the economy.

Congressional Budget Office data show that if revenues were maintained through 2050 at the historical average level of 18.3 percent of GDP, then by 2050, balancing the budget through changes in Medicare, Social Security, and Medicaid would require cutting expenditures for those programs nearly in half (by 46 percent) by that time, relative to what their costs would be under current policies.[6]

Keeping health care costs per beneficiary in Medicare and Medicaid from rising any faster than GDP per capita — a virtual impossibility given the advances in medical technology that are expected — and restoring 75-year solvency to Social Security without providing any new revenues for the program — which would entail deep benefit reductions — would be barely sufficient to achieve cuts of this magnitude in the three large programs.[7]

Moreover, even if it were possible (as a matter of politics or policy) to impose cuts of this magnitude, doing so would have disturbing consequences. Social Security cuts of this magnitude would undermine the program’s ability to provide income security for retirees, people with disabilities, and their dependents and cause substantial hardship. In Medicare and Medicaid, since system-wide health care costs per beneficiary almost certainly will continue rising faster than per capita GDP even if policymakers enact substantial reforms to the nation’s health care system, benefit reductions on this scale would lead to what Comptroller General David Walker has described as a “two-tiered” health care system. In such a “two-tiered” system, individuals in the private health system would receive one standard of care and Medicare and Medicaid’s elderly, disabled, and poor beneficiaries would receive care of much lower quality and gradually lose access to the newest and most promising medical treatments.[8]

Over the next 45 years, the nation is projected to grow substantially richer. Per-capita GDP is expected to increase by 74 percent, after adjustment for inflation. As a result, even if revenues were to grow modestly as a share of the economy, as will be necessary if the government is to continue operating important programs and services in the years ahead, individuals would still see substantial growth in their after-tax incomes, adjusted for inflation.

Some maintain, however, that the United States cannot afford to raise more revenue. They contend that even modest increases in revenues as a share of the economy would drastically reduce economic growth. The evidence is not consistent with such claims.

One way to test the idea that higher taxes have large negative effects on economic performance is to look at the relationship between tax rates and economic performance across countries and over time. If higher taxes did have large negative effects on economic growth, one would expect to see relatively strong economic performance in times and places where taxes were low and relatively poor economic performance in times and places where taxes were high.

The historical and cross-country data do not show such a relationship. As Brookings Institution economists Henry Aaron and William Gale and now-CBO director Peter Orszag explained:

Historical evidence shows no clear correlation between tax rates and economic growth. The United States has enjoyed rapid growth both when taxes were low and when taxes were high. The strongest recent extended period of growth in U.S. history spanned the two decades from the late 1940s to the late 1960s, when the top marginal personal income tax rates were 70 percent or higher. Economic growth accelerated after the top marginal tax rate was increased from 31 percent to 39.6 percent in 1993. Comparisons across countries confirm that rapid growth has been a feature of both high- and low-tax nations.[9]

Of course, the absence of clear correlation between tax rates and economic performance does not necessarily indicate that no such relationship exists. It is conceivable that high-tax countries tend to adopt other policies or have other characteristics that increase economic performance, thereby masking any underlying negative relationship between taxes and economic performance. Accordingly, economists have undertaken more sophisticated analyses. Many of these more sophisticated studies have failed to find any negative effects of higher levels of taxes on growth in developed countries; others have found only small effects.[10]

In a recent paper, economists Gayle Allard and Peter Lindert undertook a particularly intensive examination of economic performance in developed countries since the 1960s.[11] They examined the relationship between economic performance and government policy choices in a wide variety of areas, including tax policy, spending policy, and regulatory policy in product and labor markets. They controlled for various economic and demographic factors that also could be expected to affect economic performance. By simultaneously examining the impact of several types of policies and the impact of economic and demographic factors, they were able to disentangle the effects of particular policies from the most plausible sources of confounding influences.

Allard and Lindert found that, at least at levels of taxation at or even significantly above those currently seen in the United States, increasing the ratio of revenues to GDP has tended to modestly increase economic performance.[12] The authors explain this seemingly surprising result by noting that the additional revenues raised by higher-tax countries are frequently used to undertake growth-promoting activities, like investing in public education, infrastructure, and public health.[13]

The Allard and Lindert analysis undermines commonly heard arguments that higher taxes have led to weaker economic performance elsewhere in the developed world, particularly Europe. It finds that somewhat lower output per person in Europe is attributable to important differences between Europe and the United States that have nothing to do with taxes — specifically, substantially stricter regulations in product markets and labor markets in Europe, especially so-called “employee protection laws” that make it very difficult to terminate underperforming workers in some European countries.[14]

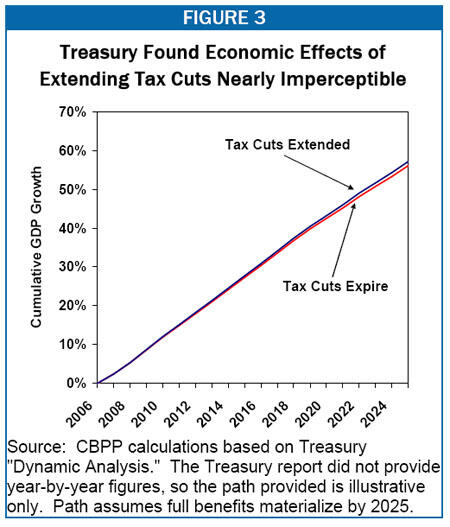

It is also worth noting that even the Bush Administration’s own Treasury Department has concluded that modest changes in taxes as a share of the economy have nearly imperceptible effects on long-run economic performance. (See Figure 3.) In a “dynamic analysis” of the effects of extending the President’s tax cuts, the Treasury found that extending the tax cuts (and paying for them by cutting spending that the Treasury model assumed has no economic benefits of its own) would increase the size of the economy by less than 1 percent over the long run. In other words, even under the Administration’s own optimistic assumptions, if the full economic benefits of the tax cuts were to materialize by 2025, they would increase total economic growth over the period 2006 to 2025 from 56 percent without the tax cuts to 57 percent with the tax cuts. Moreover, after 2025, economic growth would return to exactly the same rate it would have achieved in the absence of the tax cuts.[15]

Furthermore, to the extent that modestly higher revenue levels would create economic costs, those costs would be minor in comparison to the economic costs associated with massive deficits, the only other option available if the nation is to avoid draconian program cuts. As CBO has concluded:

Alternative ways for resolving the nation’s long-term budget problems carry different implications for the economy, but those economic implications pale in comparison to the economic costs the nation would face in the long run if federal deficits were allowed to grow faster than the economy for [an] extended period of time. If the budget was on a sustainable track, real GDP could more than double between now and 2050. Failure to achieve fiscal sustainability, however, could put the long-run growth of the economy at risk — so moving the budget toward a sustainable track [including doing so in part or in whole through revenue increases] provides substantial economic benefits in the long run. [16]

Numerous other analysts have looked at the long-run economic effects of financing lower revenues through deficits and come to similar conclusions. For example, in an analysis of the effects of reductions in individual and corporate tax rates that are not paid for, and are deficit financed, the Joint Committee on Taxation found that: “Growth effects eventually become negative without offsetting fiscal policy for each of the proposals, because accumulating Federal government debt crowds out private investment.” [17]

The historical average level of revenues does not provide a reasonable benchmark for the level of revenues that will be necessary or appropriate in the future. Revenues at this level were not sufficient to support essential public services over the past 30 years and generated chronic deficits that left the debt-to-GDP ratio substantially higher than at the start of this period. In coming decades, rising health costs and the aging of the population will increase the demands on the public sector. While it will be essential to moderate those demands through sensible program reforms and measures intended to slow cost growth throughout the U.S. health care system, revenues will need to rise significantly above the historical average. The only alternative is to institute draconian cuts that would alter the nature of American society by subjecting tens of millions of Americans who are elderly, have disabilities, or are poor to serious hardship and by placing a variety of basic functions such as education, medical research, and infrastructure investment at risk.

Contrary to claims commonly made by those who advocate solving the nation’s long-term fiscal problems solely on the spending side of the budget, well-designed revenue increases need not impose large economic costs. (See footnote 1.) This means that debates about whether the nation’s path back to fiscal sustainability should emphasize spending cuts alone or combine reasonable reforms on the spending side with revenues somewhat above the historical average are not, at their core, debates about economics. In reality, they are debates about the nation’s values and its priorities for the decades ahead.