- Home

- Sequestration Replacement Package Should...

Sequestration Replacement Package Should Maintain Parity Principle Set by Budget Control Act

Senate Budget Committee Chair Patty Murray (D-WA) and House Budget Committee Chair Paul Ryan (R-WI) have said they intend to focus the recently started budget negotiations on replacing sequestration (in whole or in part) for the next year or two with alternative deficit-reduction measures. An agreement to ease the sequestration cuts should reflect the following principles:

- Any relief from sequestration should be evenly split between defense and non-defense programs. This is necessary to maintain the principle of parity that the 2011 Budget Control Act (BCA) established when it divided the sequestration cuts evenly between defense and non-defense programs.

-

The savings needed to replace sequestration should come from both spending cuts and revenues. Some have proposed that the sole financing mechanism for replacing sequestration cuts should be domestic entitlement cuts. This would mean that domestic entitlement cuts would replace both defense and non-defense sequestration cuts. Under this approach, the net result would be much largeroverall cuts in non-defense programs than under sequestration alone. Policymakers should identify tax loopholes to close and other savings outside of domestic entitlements that, at a minimum, can replace the defense sequestration cuts.

Of particular concern, using non-defense entitlements as the sole source of savings for even a year or two of sequestration relief could set a dangerous precedent for any future deal for sequestration relief. Replacing all eight years of sequestration (2014-2021) would require about $900 billion in savings. Entitlement cuts of that magnitude would almost certainly require cutting benefits in key programs that serve millions of low- and moderate-income children, seniors, people with disabilities, and families that work for (or have earned) modest wages — programs such as Social Security, Medicaid, Medicare, and SNAP.

Thus, a more balanced set of deficit-reduction measures will be needed to replace sequestration over the coming decade. Policymakers should start down that path now, rather than set a deeply troubling precedent.

- Policymakers should design sequestration relief to help the still-struggling economy. Sequestration is acting as a drag on the recovery. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) states that if policymakers canceled sequestration for 2014, the economy would have the equivalent of 800,000 more full-time jobs, and real (inflation-adjusted) gross domestic product (GDP) would be 0.6 percent larger, in the fourth quarter of next year than under current projections.[1] Replacing sequestration for 2014 and 2015 with measures that produce equivalent savings over the decade, but phase in more gradually, would both help the economy now and provide more deficit reduction than sequestration over the longer term.

Policymakers have an opportunity to strengthen the economy and undo some or all of the sequestration cuts for the immediate future by replacing them with better designed, better timed deficit-reduction measures. If those measures include both revenues and spending cuts and provide relief to non-defense areas as well as defense, the result can be a balanced package that reverses the worst of the sequestration cuts, bolsters near-term economic growth, and lowers longer-term deficits.

If, however, policymakers set the precedent that only domestic entitlement cuts can replace sequestration, they likely won’t be able to agree on replacing sequestration in subsequent years or will ultimately replace it with hefty cuts in basic assistance and social insurance programs that worsen poverty and hardship.

Image

Like Sequestration Cuts, Sequestration Relief Should Affect Defense and Non-Defense Equally

Like Sequestration Cuts, Sequestration Relief Should Affect Defense and Non-Defense Equally

The Budget Control Act imposed annual caps on discretionary funding through 2021 and established the so-called “supercommittee” to develop a plan to achieve at least $1.2 trillion in additional deficit reduction. If Congress failed to enact such a plan, the BCA called for $109 billion in annual sequestration cuts — equally divided between defense and non-defense programs — from 2013 through 2021, to reduce the deficit.

Congress failed to reach a deficit-reduction agreement, so sequestration took effect. Most of the cuts are to discretionary programs, but some entitlements also are subject to sequestration, including Medicare, federal unemployment benefits, and the Social Services Block Grant.

Just as the BCA called for an even split in sequestration cuts between defense and non-defense programs, any package that replaces some or all of those cuts with alternative deficit reduction should provide equal relief to both sets of programs. Adhering to this core principle of parity recognizes that sequestration has left significant gaps in key non-defense areas — from medical research to public health and safety to education — and also reduced defense funding to levels that concern many policymakers.

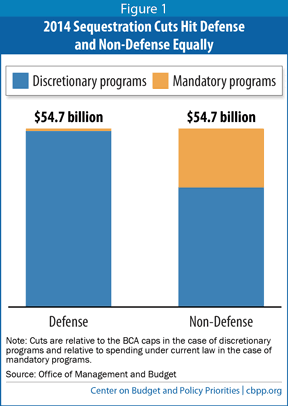

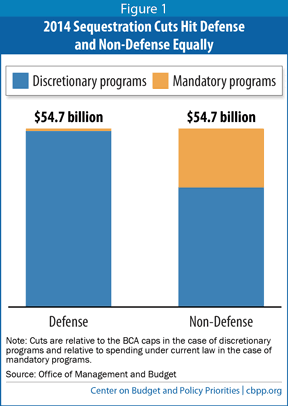

Some argue, instead, that defense should have first claim on sequestration relief, asserting that the 2014 sequestration targets defense disproportionately. This impression is mistaken (see Figure 1). While defense discretionary funding will fall by $20 billion from 2013 to 2014 if sequestration remains in effect, this year-to-year decline occurs because defense received $20 billion more funding in 2013 than the BCA originally provided, primarily from one-time provisions in the “fiscal cliff” bill enacted in January 2013.[2] Funding for non-defense discretionary programs is scheduled to remain flat under sequestration in 2014 because that part of the budget did not benefit from these one-time relief measures in 2013. (See box for details.)

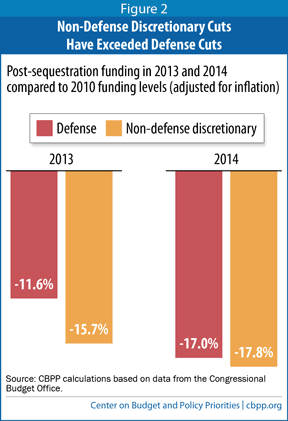

Further evidence that sequestration does not target defense disproportionately is that policymakers have cut non-defense discretionary programs more deeply than defense since 2010, when they began efforts to shrink deficits. This will continue to be the case in 2014 even if sequestration remains in effect and defense funding falls $20 billion below its 2013 level (see Figure 2).

The effects of these cuts in non-defense discretionary programs are likely to become more severe in 2014 if sequestration is continued. In some cases, agencies were able to mitigate the impact of sequestration in 2013 with one-time funds that have now been depleted. For instance, housing agencies relied on program reserves to soften sequestration’s cuts in rental assistance for low-income families in 2013, but the reserves at many of these agencies will likely be exhausted during 2014, leading to two to three times as many low-income households being denied assistance next year if sequestration continues.[3] In other cases, the effects of these cuts cumulate. For instance, the medical research projects that NIH won’t fund in 2014 if sequestration continues will be in addition to the research projects that were not funded in 2013 due to sequestration.

Explaining the Defense Sequestration Cuts in 2013 and 2014

Under the Budget Control Act (BCA), sequestration in 2014 will entail $109 billion in cuts, evenly divided between defense and non-defense programs. To comply with sequestration in 2014, however, defense discretionary funding must come down about $20 billion from its 2013 funding level, while funding for non-defense discretionary programs would essentially remain flat. This apparent disconnect is largely a function of one-time changes that disrupted the balance between defense and non-defense discretionary funding cuts under sequestration in 2013, in favor of defense.

These one-time changes raised defense funding in 2013 by $20 billion over the level called for in the original BCA if sequestration was triggered, while providing no net relief to non-defense programs. As Goldman Sachs recently noted, the sequestration cuts “fell more heavily on non-defense spending in FY2013, but will fall equally on defense and non-defense spending in 2014.”a

These one-time changes in 2013 included the following:

- In the “fiscal cliff” bill enacted at the start of the year, policymakers reduced the size of the 2013 sequestration, primarily by cancelling the first two months of the cuts. These changes reduced the size of the sequestration cuts in 2013 funding for both the defense and non-defense categories.

- The fiscal cliff bill also changed the composition of the two discretionary caps, shifting from caps on “defense” and “non-defense” funding to caps on “security” and “non-security” funding. The “security” funding category includes not only defense programs but also non-defense areas such as international affairs, homeland security, and veterans’ programs. This switch allowed Congress to provide more funding for the defense portion of the security category than would have been possible under the original defense sequestration cap for 2013. Thus, these changes increased defense funding but reduced overall non-defense funding in 2013.

- Finally, a technical factor in the application of sequestration known as the “crediting rule” permitted a modest amount of the 2013 sequestration to be cancelled. The bulk of this benefit went to defense programs.

As a result of these changes, defense ended up receiving roughly $20 billion more funding in 2013 than originally called for under sequestration. In contrast, the various one-time changes were largely offsetting for non-defense discretionary programs. This is why defense funding drops by $20 billion between 2013 and 2014 under sequestration, while non-defense funding remains flat. This treatment simply restores the equal application of sequestration to defense and non-defense programs that lies at the heart of the BCA but was temporarily disrupted in 2013.

a Goldman Sachs Global Economics, Commodities and Strategy Research, “The Probability of a Small Deal is Rising,” November 5, 2013.

Sequestration Relief Should Not Increase the Cuts to Non-Defense Programs

There is broad agreement that the sequestration cuts are poorly designed. But policymakers would be well-advised not to replace one set of harmful cuts with another set of harmful cuts.

Since 2010, policymakers have enacted several deficit-reduction measures that, taken together, will shrink deficits by $4 trillion over the 2014-2023 period if sequestration remains in place. (This $4 trillion reflects policy changes and the accompanying interest savings, not the effects of an improving economy or the phasing out of temporary stimulus provisions.) Some 79 percent of the policy savings come from spending cuts. Just 21 percent come from revenue increases.[4]

| Table 1 Deficit Reduction Enacted to Date, 2014-2023 | |||

| Policy Savings | Interest Savings | Total Deficit Reduction | |

| Discretionary savings from cuts in 2011 funding and caps imposed by the BCA* (excluding sequestration) | $1.58 trillion | $340 billion | $1.92 trillion |

| Savings from ATRA* (includes revenues and spending cuts) | $732 billion | $119 billion | $851 billion |

| Total before sequestration | $2.31 trillion | $458 billion | $2.77 trillion |

| Sequestration cuts | $976 billion | $224 billion | $1.2 trillion |

| Total with sequestration | $3.28 trillion | $682 billion | $3.97 trillion |

| *BCA=Budget Control Act; ATRA=American Taxpayer Relief Act Source: CBPP based on Congressional Budget Office and Joint Committee on Taxation data. | |||

In the budget negotiations that recently started, congressional Democratic leaders have emphasized that any replacement for part or all of sequestration should include both spending cuts and revenues. Even if policymakers replaced half of the sequestration cuts in 2014 and beyond with revenues, nearly two-thirds of the deficit reduction achieved over the 2014-2023 period still would come from spending cuts.

Key Republicans, by contrast, have called for cuts in domestic entitlements to be the sole source of relief from sequestration. Under this approach, spending cuts would continue outpacing revenue increases by 4 to 1, and non-defense programs would bear a larger share of the cuts than under sequestration, since new non-defense cuts would replace the defense sequestration cuts.

Relying entirely on domestic entitlement cuts to undo sequestration would also overturn a key piece of the compromise that led to the BCA. In the negotiations over that compromise, the Administration proposed that the automatic deficit-reduction measures that would be triggered if the supercommittee failed should be evenly divided between spending cuts and revenue increases. When Republicans rejected that approach, the two sides agreed that half of the savings would come from defense programs and half from non-defense; they agreed that sequestration’s goal was to prod both parties to negotiate a deficit-reduction package. For policymakers now to shift more cuts to non-defense programs, without any new contributions from revenues, would turn that deal on its head.

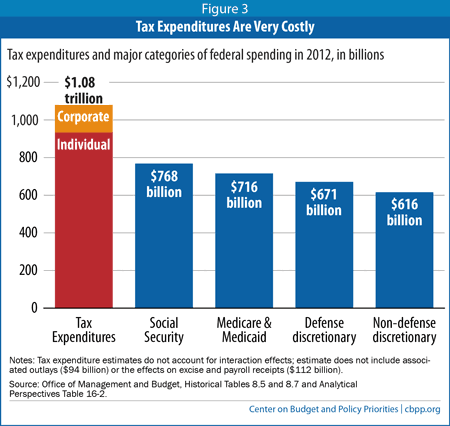

Policymakers thus should avoid a sequestration-replacement package in which all of the savings come from non-defense programs. At a minimum, they need to consider other replacements for the defense sequestration cuts. These should include revenues and could also include user fees and reforms in defense-related entitlements such as military-related health and pension benefits.

While it may be possible to come up with enough domestic entitlement cuts that represent reasonable policies and don’t harm vulnerable individuals to offset some of the sequestration cuts for a year or two, the amount of such “low-hanging fruit” is modest. To fully replace sequestration over the next decade would take more than $900 billion in cuts. Domestic entitlement cuts of that magnitude would almost inevitably have a significant impact on key programs that assist millions of low- and moderate-income children, seniors, people with disabilities, or families that work for (or have earned) modest wages.

Thus, replacing the remaining years of sequestration cuts entirely with entitlement cuts — with no contribution from tax expenditures — would represent a major retreat from the principle of balance in deficit reduction. And, it almost certainly would mean that deficit reduction would exacerbate inequality and increase poverty and hardship, going against a key principle embodied in prior large-scale deficit-reduction legislation and articulated more recently by fiscal commission co-chairs Alan Simpson and Erskine Bowles.

A few basic figures explain why this is the case. The majority of entitlement benefits go to the bottom two-fifths of the population, while the majority of tax-expenditure benefits go to the top fifth.

Sequestration Relief Should Help, Not Hinder, the Still-Struggling Economy

The current budget negotiations occur against a backdrop of continued economic weakness. Despite 44 consecutive months of private-sector job growth, overall unemployment and long-term unemployment remain high. Moreover, the share of the population with a job has barely improved since the recession hit bottom.

Sequestration is part of the problem. According to CBO, if policymakers cancel the 2014 sequestration cuts, the economy would have 800,000 more full-time-equivalent jobs, and real GDP would be 0.6 percent larger in the fourth quarter of next year, than under current projections.[5]

Cutting spending when the economy is weak places a drag on growth and jobs. Cutting less now would help the economy. Thus, replacing sequestration in 2014 and 2015 with alternative deficit reduction that takes effect as the economy strengthens and produces equivalent savings over the coming decade as a whole would be better for the economy than keeping sequestration in place.

Such an approach also would be better for our medium- and longer-term fiscal challenges because it would focus the deficit reduction in the latter years of this decade and in future decades. Deficits in the next few years aren’t the problem. Even without sequestration, deficits are projected to be below 3 percent of GDP over the 2015-2018 period before beginning to edge up. Doing less deficit reduction in the near term and more over the longer term would target deficit reduction to where it’s needed more, while fostering economic growth and job creation now.

End Notes

[1] Congressional Budget Office, Letter to the Honorable Chris Van Hollen, “Re: Economic Effects in 2014 of Eliminating the Automatic Spending Reductions Specified in the Budget Control Act,” September 26, 2013.

[2] Joel Friedman, Richard Kogan and Sharon Parrott, “Clearing Up Misunderstandings: Sequestration Would Not Be Tougher on Defense Than Non-Defense Programs in 2014,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, September 18, 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=4019.

[3] Doug Rice, “Sequestration Could Cut Housing Vouchers for as Many as 185,000 Low-Income Families by the End of 2014,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, November 6, 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=4044.

[4] Sharon Parrott, Richard Kogan, Krista Ruffini, and William Chen, “Chart Book: Deficit Reduction, the Economy, and the Budget Negotiations,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, November 5, 2013, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=4043.

[5] Congressional Budget Office.

More from the Authors

Areas of Expertise