- Home

- Portman Proposal For Automatic Continuin...

Portman Proposal for Automatic Continuing Resolutions Would Impede Appropriations Process and Could Produce Very Deep Funding Cuts

Senator Rob Portman (R-OH) has introduced legislation under which a year-long “continuing resolution” would take effect automatically — and force ever deeper funding cuts over the course of the year — if policymakers have not enacted one or more appropriations bills or a temporary continuing resolution by the start of the fiscal year.[1] The proposal’s stated purpose is to avoid government shutdowns. But its principal effect would probably be to make appropriations bills harder to pass by enabling lawmakers who oppose certain appropriations bills to impede them without risking a shutdown.

Under the proposal, Congress would no longer need to pass appropriation bills, and the President would no longer need to sign them. This would increase the likelihood that program funding would be set by a mechanical formula instead of case-by-case, program-by-program policy decisions.

The Portman proposal would apply to any individual appropriations bill that was not enacted or covered by a regular continuing resolution by the start of the fiscal year. The automatic, mechanical formula would force progressively deeper cuts, making the Portman proposal a variation on sequestration — and notably more restrictive than the current sequestration law. Indeed, if it were in place this year and continued throughout the decade, and it applied to all of the annual appropriations bills, the mechanical Portman cuts would reduce discretionary funding for the period 2014-2023 by $2.6 trillion below the post-sequestration funding caps under existing law. Yet three decades of experience show that the threat of sequestration is not effective in forcing unwilling policymakers to compromise, while often leading to undesirable results.

Proposal Would Produce Ever-Growing Funding Cuts

Under the proposal, an automatic continuing resolution (CR) would go into effect if neither a regular appropriations bill nor a temporary CR has been enacted by October 1 or if a temporary CR has expired. (A CR typically continues funding at rates set by formula if Congress and the President have not enacted normal, full-year appropriations bills by October 1, the start of the fiscal year. A temporary CR covers only a portion of the fiscal year, with the expectation or hope that Congress will pass full-year appropriations bills during the period covered by the CR.) Portman’s automatic CR would apply to any or all of the 12 annual appropriations bills that are supposed to be enacted each year, if funding for those bills lapses.[2] Under the Portman proposal, the automatic CR would last for the entire fiscal year unless superseded by enactment of a regular appropriations bill.

- for the first 120 days, at the prior year’s rate of operation;

- for the next 90 days, at 1 percentage point lower than the prior year’s rate (i.e., at 99 percent of the prior year’s rate of operation); and

- for each subsequent 90-day period, at another percentage point lower.

To illustrate, suppose the Portman proposal were existing law and (as actually happened) Congress failed to enact appropriations bills or alternative CRs by October 1, 2013, the beginning of fiscal year 2014. Under this scenario, affected programs would operate at 100 percent of the post-sequestration 2013 level through January 28, 2014. Operating levels would then fall to 99 percent of the post-sequestration 2013 level through April 28, to 98 percent through July 27, and to 97 percent for the remaining 65 days of 2014.

Moreover, the proposal appears to define this ultimate 97-percent operating level as the new “100 percent” level for the next fiscal year, 2015. Thus, if Congress remained unable to enact regular appropriations or some alternative CR, funding for affected programs would continue to ratchet down year after year.

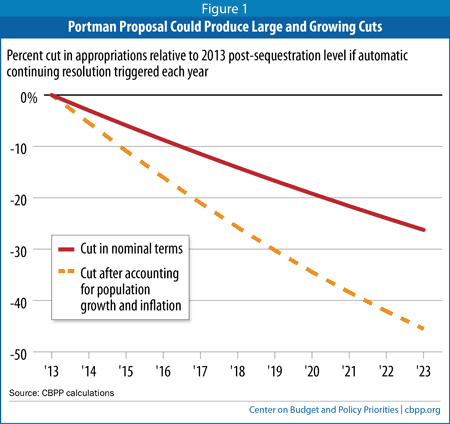

Figure 1 shows what would happen if the Portman cuts continued indefinitely. Funding for any bills covered by the proposal would fall 10 percent below the 2013 post-sequestration level by the fourth year, 20 percent below by the eighth year, and 26 percent below by the tenth year. If one accounts for inflation and the growth of the U.S. population, the effective cuts would be even deeper — 46 percent below the 2013 post-sequestration level by the tenth year. The Portman cuts, if continued over the ten-year period 2014-2023 and applicable to all discretionary funding, would be $3.5 trillion below the discretionary caps in the Budget Control Act (BCA) and $2.6 trillion below those caps as further reduced by sequestration if sequestration remained in effect throughout this period.[3]

Automatic CR Could Impede Enactment of Appropriations Bills

Although the automatic CR proposal is advertised as a mechanism to avert government shutdowns, its principal effect would probably be to impede agreement on individual appropriations bills, since a year-long CR would kick in automatically.

Suppose that in a given year, the House or 41 senators prefer the reduced funding level under the automatic CR for one or more appropriations bills to the level that is being considered. The House or Senate might be more likely to fail to pass an appropriations bill without coming up with an alternative — or a minority of 41 senators might feel emboldened to filibuster an appropriations bill — since doing so would not threaten a shutdown or disruption of government operations.

The automatic CR provision thus could draw out what already is a lengthy appropriations process and increase the chances of appropriations bills never being enacted. Congress would no longer need to pass appropriations bills, and the President would no longer need to sign them. Those who seek to keep shrinking the government would have a path to victory, even if one chamber and the President — or a majority of both chambers and the President but not a filibuster-proof majority in the Senate — oppose their views. Failure to appropriate could become a common occurrence.

The current appropriations process puts a premium on reasonableness and willingness to compromise, since it is irresponsible for the President, a House majority, or a Senate minority to refuse to pass an appropriations bill without an alternative. An automatic CR waiting in the wings would make it much easier for policymakers to veto, defeat, or filibuster an appropriations bill.

Retarding Efforts to Improve Efficiency

Relying upon automatic CRs rather than passing regular appropriations bills also would reduce government efficiency, since it would keep Congress from moving resources from less effective programs to more effective ones. Funding levels for programs covered by automatic CRs would be stuck at the level dictated by the automatic CR formula, rather than raised for some programs and lowered for others to reflect changes in need, effectiveness, or public preferences. The status quo would be reinforced at the expense of more responsive and effective government.

What Problem Does an “Automatic” Continuing Resolution Solve?

The automatic CR is supposed to prevent government shutdowns caused by a failure to pass either appropriations bills or any CR. But it is not difficult to enact CRs; Congress has enacted 97 since 1996.

Two government shutdowns occurred in the early part of fiscal year 1996 and one last October, but those shutdowns were deliberate. Supporters described them as a method of compelling first President Clinton and then President Obama to accede to budget policies that could not otherwise be enacted, most recently to defund or repeal health reform. In each case, the public proved unsympathetic, and the tactic failed.

It should also be noted that the Portman proposal would be of no help if the United States experiences a government shutdown in the form of a Treasury default, caused if Congress fails to raise the debt limit and the Treasury exhausts the “extraordinary measures” it can use during a debt-limit crisis. The Portman proposal continues appropriations. But a debt-limit shutdown (if it ever happened) would occur not because of a lack of appropriations but because the Treasury lacked the authority to borrow to pay bills as they become due, even though appropriations existed.

Permitting “Hands-Off Budget Cutting”

An automatic CR also could lead to reductions in overall discretionary funding below the levels agreed to in the congressional budget resolution or in the 2011 Budget Control Act’s discretionary caps. The appropriations committees typically allocate available resources so that funding levels rise for some appropriations bills and fall for others; that is a normal part of setting priorities and responding to changing conditions. Under the automatic CR proposal, any bill slated for a funding increase — or even a freeze — could be a target for budget cutters, who might have the votes to filibuster or defeat the bill without having to design or support an alternative.

As a result, the automatic CR procedure could encourage those who seek to shrink government and lower discretionary funding to impede progress on certain appropriation bills, seeking instead to fund the programs covered in those bills through a restrictive, automatic CR.

In effect, the automatic cuts would create a form of “hands-off budget cutting.” Programs would be cut automatically without members of Congress having to vote for specific appropriation bills that impose the cuts.

Unlikely to Create Incentives for Compromise

The automatic cuts in the Portman proposal are analogous to the automatic “supercommittee” sequestration. They are also analogous to the automatic sequestration under Gramm-Rudman-Hollings (GRH) I and II of 1985 and 1987. In each case, advocates claimed that the threatened sequestration would be so mutually distasteful that it would compel policymakers of very different views to compromise. In reality, however, GRH I and GRH II did not induce President Reagan to agree to revenue increases; instead, he used rosy economic scenarios, timing shifts, and assets sales to largely avoid sequestration. Similarly, in 2011 the BCA’s supercommittee achieved none of its targeted $1.2 trillion in deficit reduction; instead, sequestration was the automatic result.

In short, history lends no credence to the notion that automatic cuts, as under the Portman proposal, induce moderation and compromise. Just the opposite: automatic hands-off budget cutting makes mindless, across-the-board cuts more likely rather than less so.

Automatic CR Also Would Disrupt Funding for Certain Entitlement Programs

Some entitlement programs such as veterans’ compensation and pensions, Medicaid, Supplemental Security Income, vocational rehabilitation, SNAP, and crop insurance are funded through annual appropriations bills. The automatic CR in the Portman proposal appears to fund these programs, like all others, via the automatic CR formula. In most years, that formula would fail to provide sufficient funding for most entitlement programs because the formula does not account for either inflation or growth in the U.S. population. Nor does it account for an increased number of families qualifying for programs such as Medicaid and SNAP during recessions.

In such circumstances, the insufficient funding provided by the automatic CR would necessitate “supplemental” appropriations later in the fiscal year to meet entitlement funding requirements and comply with the authorizing statutes that govern these entitlement programs. Supplemental appropriations bills, however, have the drawback of being time-consuming, risking disruption at federal agencies and in the delivery of needed benefits, and possibly becoming vehicles for unnecessary add-ons in a variety of programs.

End Notes

[1] See S. 29, 113th Congress, 1st Session, the “End Government Shutdowns” Act, introduced January 22, 2013, by Senator Rob Portman.

[2] Funding lapsed for a vast swath of the government on October 1, 2013, the first day of fiscal year 2014, because neither regular appropriations bills nor a temporary CR had been enacted. Funding also could lapse during the fiscal year if regular appropriations are not enacted by the start of the fiscal year but a temporary CR is enacted, and that temporary CR then expires and is not renewed or replaced. Whether funding lapses on October 1 or later in the fiscal year, and whether the lapse affects one bill or all of the 12 regular appropriations bills, the Portman formula would kick in and would apply to the bills that have lapsed.

[3] The BCA caps extend through 2021. In its budget baseline, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has calculated what the caps would be each year after applying the cap reductions (i.e., sequestration) triggered by the failure of the 2011 supercommittee to negotiate a deficit reduction plan. CBO has also effectively extended the caps past 2021 by assuming that the 2021 caps grow with inflation in years after 2021. We use CBO’s estimates.