- Home

- Gregg Bill Would Make Far-Reaching Chang...

Gregg Bill Would Make Far-Reaching Changes In Budget Rules

Bill Would Aim Budget Knife at Domestic Programs While Shielding Tax Cuts from Fiscal Discipline

Executive Summary

Sweeping legislation to radically alter federal budget procedures, designed by Senate Budget Committee chairman Judd Gregg and endorsed by Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist, was adopted by the Budget Committee on June 20. The bill may be brought to the Senate floor this summer (either as a single piece of legislation or as several separate bills). The legislation seeks to force dramatic changes in the budget. If enacted, it could have profound effects on American society.

In unveiling the bill earlier in June, Senator Gregg described it in moderate terms as offering “common-sense and fiscally responsible solutions” to problems like “duplicative and wasteful spending.” The legislation fails, however, to include common-sense budget reforms that have proved effective in the past, such as restoration of the Pay-As-You-Go rules on entitlement increases and tax cuts. Instead, the bill contains radical measures that could lead to massive cuts over time in Medicaid and Medicare and reductions in the vast majority of domestic programs, while shielding tax cuts from any fiscal discipline. The bill would do the following:

-

Impose caps on funding for discretionary programs that would force substantial cuts in public services. The Gregg bill would lock in, for the next three years, the overall discretionary funding levels proposed in President Bush’s most recent budget. To hit those levels, the President’s budget proposes $66 billion in domestic discretionary cuts over the next three years. By 2009, the President’s cuts would hit every domestic discretionary program area in the budget, with the sole exception of space, science, and technology.

-

Set fixed deficit targets, falling to 0.5 percent of GDP by 2012, enforced by automatic across-the-board cuts in all entitlement programs except Social Security. CBO’s budget projections indicate that if the President’s tax cuts (except for estate-tax repeal) are made permanent,[1] relief from the Alternate Minimum Tax is continued, the President’s defense build-up is funded, and operations in Iraq and Afghanistan phase out over the next several years, the deficit will equal 1.9 percent of GDP in 2012. The gap between this projected deficit and the 0.5 percent of GDP deficit target in the Gregg bill would amount to $244 billion in 2012. If Congress did not enact legislation to close this gap, this entire $244 billion in savings would have to be achieved through across-the-board cuts in entitlement programs, including basic assistance programs for the poor and the unemployed, veterans programs, and Medicare. (The discretionary caps, if adhered to, would close some of this gap; new tax cuts, on the other hand, would widen it.)

-

Establish new definitions of “solvency” for Medicare and Medicaid that are unrelated to how these programs are financed, have a marked ideological tilt, and could not be met without harsh changes. The legislation would define Medicaid “solvency” in a way that likely could be achieved only by abolishing Medicaid in its current form and replacing it with a block grant to states under which federal funding would grow much more slowly than health care costs, and with no allowance being made for the increased Medicaid costs that will result from the aging of the population. To meet this “solvency” target, federal Medicaid funding would have to be cut a stunning 22 percent by 2020, 36 percent by 2030, and 50 percent by 2042 (relative to CBO’s baseline projections).

Similarly, meeting the Gregg bill’s Medicare “solvency” target would require massive increases over time in the premiums, deductibles, and co-payments that elderly and disabled Medicare beneficiaries pay, sharp restrictions on the health care services that Medicare covers, or cuts in payments to health care providers that could exceed 30 percent by 2030. -

Establish a “fast-track” legislative mechanism that could allow a narrow partisan majority to ram through Congress terminations of (and major changes in) discretionary and entitlement programs. The bill would establish a commission to propose legislation calling for program terminations and realignments (such as consolidations of programs into block grants at reduced funding levels). The bill would allow a bare partisan majority on the commission to approve the plan, and allow the plan then to be pushed through Congress under fast-track procedures without any minority-party votes needed — and with no amendments allowed either in committee or on the House and Senate floors. With their votes irrelevant and their amendments disallowed, members of the minority party could effectively be disenfranchised.

Shielding Tax Cuts from Fiscal Discipline

While establishing procedures that could trigger cuts in everything from education to school lunches and benefits for disabled veterans, the Gregg bill would shield tax cuts from fiscal discipline. The Urban Institute-Brookings Institution Tax Policy Center estimates that the tax cuts enacted in 2001 and 2003 are now worth an average of $112,000 a year to households with annual incomes of over $1 million and that the average tax cut for these households will reach more than $130,000 (in today’s dollars) by 2012 if the tax cuts are extended. Data from the Tax Policy Center and the Joint Committee on Taxation also indicate that the cumulative cost of the tax cuts just for the top 1 percent of the Americans (those with incomes over about $400,000 in 2006) will approach $1 trillion over the coming decade. Moreover, CBO data indicate that the tax cuts enacted since 2001 have been responsible for as much of the increase in the deficit over the 2002-2011 period as all domestic, defense, and international spending increases combined since 2001, including the spending on the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The Gregg bill would protect the tax cuts. It would, if Congress continues to fully fund the President’s military requests, place virtually all of the burden of addressing the nation’s fiscal problems on domestic programs, including programs upon which tens of millions of Americans of modest means rely.

Cuts in Domestic Discretionary Programs

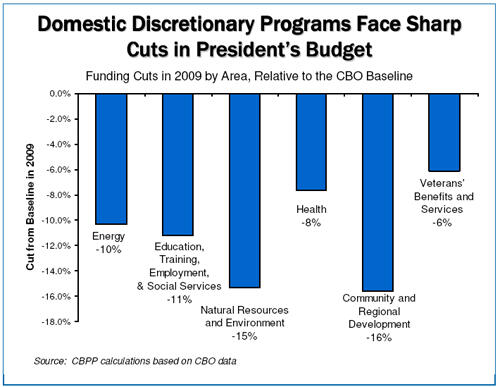

As noted, the Gregg bill would cap overall discretionary funding levels for the next three years at the levels proposed in the President’s budget. That budget proposes $66 billion in cuts in domestic discretionary programs over the next three years, with the cuts growing deeper each year. The cuts proposed by the President would touch almost all categories of domestic programs, with even high-priority areas slated for substantial cuts (see chart below).

For example, under the President’s budget, the acclaimed women, infants, and children nutrition program (WIC), which the Bush White House has singled out for praise as one of the most effective federal programs, would be cut $459 million in 2009. That would entail reducing the number of low-income pregnant women, infants, and young children at nutritional risk whom the program serves by an estimated 680,000.[2] Similarly, the Bush budget would cut vocational and adult education by 73.5 percent ($1.5 billion) in 2009. The Environmental Protection Agency’s clean water programs would be cut 19 percent ($354 million). The low-income home energy assistance program would be cut 49 percent ($1.6 billion). Even the National Institutes of Health would be cut 8 percent ($2.5 billion). (These reductions are measured relative to the Congressional Budget Office baseline, which equals the 2006 funding levels, adjusted for inflation.)

Deficit Target Mechanism Puts Poor Families, Veterans, and Others at Risk

The Gregg proposal would set fixed deficit targets that would decline from 2.75 percent of the Gross Domestic Product in 2007 to 0.5 percent of GDP in 2012 and every year thereafter. If these deficit targets would otherwise be missed, across-the-board entitlement cuts would automatically be triggered, with the cuts being set at whatever percentage reduction was needed to hit the target.

As noted, if the President’s tax cuts (except for full estate tax repeal) are made permanent, relief from the AMT is continued, and the President’s defense build-up is funded, the deficit will equal 1.9 percent of GDP in 2012 even if operations in Iraq and Afghanistan have been phased out by then. The gap between this projected deficit and the Gregg bill’s target (0.5 percent of GDP) would amount to $244 billion in 2012, meaning that $244 billion in deficit reduction would be required. The gap between projected deficits and the deficit target would grow larger in years after 2012, requiring even larger amounts of deficit reduction in those years.

The cuts in discretionary programs that would be needed to comply with the bill’s discretionary caps would close only about one-eighteenth of this gap. Over the ten years from 2007-2016, Congress also would have to cut entitlement programs by a cumulative total of $1.6 trillion to hit the deficit targets, unless it were willing to close part of the gap by raising revenues and/or cutting discretionary programs below the cap levels.[3]

If Congress failed to cut enough to hit a given year’s target, all of the savings needed to hit the target would be obtained through automatic, across-the-board cuts in every entitlement program except Social Security. Table 1 shows the magnitude of the cuts that would be made in various entitlement programs if the $1.6 trillion in entitlement reductions were secured through the automatic cuts (i.e., if all entitlements except Social Security were cut by the same percentage).

This component of the Gregg bill is modeled on the Gramm-Rudman-Hollings (GRH) legislation enacted in 1985 and revised in 1987 (which proved largely unsuccessful in reducing deficits for reasons discussed in the body of this analysis). But the Gregg bill departs from the GRH law in several fundamental respects. All of the departures make the Gregg approach less equitable — and more ideological — than the old GRH law.

| TABLE 1: | |

| Medicare | 693 |

| Medicaid/SCHIP | 366 |

| Federal civilian retirement | 102 |

| EITC/Child Tax Credit | 60 |

| Military retirement | 60 |

| SSI | 56 |

| Unemployment insurance | 56 |

| Veterans benefits | 50 |

| Food stamps | 45 |

| TANF, CSE, and related | 24 |

| Farm programs | 20 |

| School lunch/child nutrition | 20 |

| TRICARE | 14 |

| Foster care/adoption assistance | 10 |

| Student loans | 4 |

-

Under the old GRH law, if automatic cuts were triggered, half of the cuts had to come from defense programs and half from domestic. (The domestic cuts would be made in both discretionary and entitlement programs.) This aspect of the old GRH law was purposefully designed to be painful to policymakers from across the political spectrum, so everyone would have an incentive to try to reach agreement on bipartisan deficit-reduction measures that could avert the automatic cuts. By contrast, the Gregg bill shields defense from the automatic cuts, by limiting the automatic cuts to entitlement programs. It thereby requires that virtually all of the automatic cuts come from non-defense programs. Rather than inflicting pain on policymakers and interest groups from across the political spectrum, in hopes of bringing all of them to the negotiating table, the bill’s automatic cuts would inflict pain on one part of the budget — domestic programs.

-

In addition, under the old GRH law, basic programs for the poor — such as the Supplemental Security Income program for the elderly and disabled poor, free school lunches for poor children, food stamps, and the Earned Income Tax Credit for the working poor — were exempt from the automatic cuts. So were veterans disability compensation and veterans pensions. All budget-process laws enacted since 1985 that have contained automatic cuts have exempted these programs from those cuts. Not the Gregg bill, however. It abandons these protections. Programs for the poor and even for disabled veterans would be hit with full force when the automatic-cut axe fell.

The Gregg bill’s fixed deficit targets also represent unsound economic policy. Deficits increase when the economy slows. As a consequence, the budget cuts needed to meet the fixed deficit targets that the bill sets would be largest in the years when the economy was weakest. Economists widely regard this as an ill-advised course that stands basic economics on its head and risks tipping a faltering economy into recession.

Line-item Veto

The Gregg bill also would give the President line-item veto authority. Most budget experts are skeptical that such authority will do much to reduce deficits and believe it is likely to have more of an effect in enhancing the President’s leverage over Congress on a range of matters than in strengthening fiscal discipline.[4]

The line-item-veto provision in the Gregg bill is particularly troubling in this respect. It would give the President one year after enactment of a bill to propose the cancellation of provisions in it. It would then allow the President to withhold the funds proposed for cancellation for 45 days after submitting his veto request, regardless of Congressional action. This would enable a White House to use these procedures to withhold some appropriated funds through the end of a fiscal year, which could cause the funds to lapse — and the appropriation thereby to be cancelled — even if Congress had voted to disapprove the veto.

Moreover, the President would be allowed to package cancellation of items from different bills into a single veto package, and Congress would have to vote to accept or reject the package as a whole, with no amendments allowed. The President could combine vetoes of egregious earmarks that had received damning publicity with vetoes of more meritorious items from other bills that he opposed on ideological grounds — and confront Congress with an “all or nothing” vote. This could lead to the cancellation of some programs that, by themselves, enjoyed support from a majority of Congress. It should be noted that the line-item veto’s likely use would extend far beyond earmarks; it could be used to eliminate entire programs.

Failure to Include Key Reforms

Finally, the Gregg legislation is as notable for what it excludes as for what it includes. It fails to include the single reform that budget watchdog groups, the Government Accountability Office, and former Federal Reserve Chair Alan Greenspan all have said is critical to restoring fiscal discipline — the restoration of Pay-As-You-Go rules on both entitlement increases and tax cuts.A recent analysis that have conducted, based on CBO’s long-term budget projections through 2050, indicates that enacting — and abiding by — PAYGO rules could close as much as two-thirds of the “fiscal imbalance” through 2050.

The Gregg proposal also fails to include another reform that budget watchdog groups have stressed — restoring the original intent of the fast-track budget reconciliation process by barring its use to facilitate passage of legislation that increases deficits. Although the Gregg bill requires that entitlement increases be paid for, it allows deficit-financed tax cuts to continue being enacted without limit and also allows the continued abuse of the reconciliation process to push through large deficit-financed tax cuts.

In addition, unlike the bipartisan 1990 deficit-reduction legislation, which contained $500 billion over five years in specific program cuts and tax increases (mostly on high-income households) — and also established the PAYGO rules — the Gregg bill contains no specific policy changes. In fact, if the Gregg bill were enacted, that likely would make it more difficult to achieve a large-scale, bipartisan deficit-reduction agreement. To achieve such an agreement, policymakers from across the political spectrum must fear the consequences of failing to act and must be willing to give some ground on their own policy priorities in return for other policymakers with different priorities giving ground on theirs. Under the Gregg bill, however, policymakers on the right would likely see little reason to come to the bargaining table. Why negotiate a bipartisan agreement that likely would increase revenues, as well as cut spending, when you can do nothing and let the Gregg bill’s caps and automatic cuts place most of the burdens on domestic programs, while sparing tax cuts entirely?

The bill does include some provisions that should prove beneficial in improving budget debates, such as a provision to ensure that cost estimates are available on conference reports before those reports are voted on. Such provisions are, however, a minor part of the bill.

In short, the Gregg bill fails either to make any specific hard choices or to call for even a modicum of shared sacrifice. It is assiduous in its protection of deficit-financed tax cuts, even as it seeks to establish procedures to put domestic programs under the knife. It seeks to cloak itself in rhetoric about fiscal responsibility, but its dedication to protecting costly tax cuts from fiscal discipline makes its proclaimed commitment to fiscal responsibility ring hollow.