Statement by Chad Stone, Chief Economist, on the April Employment Report

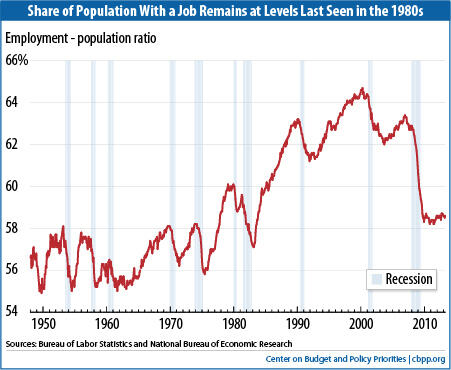

Today’s jobs report shows that labor markets still bear the scars of the Great Recession despite 38 straight months of private-sector job growth and a drop in the unemployment rate from 7.9 percent to 7.5 percent since January. Unemployment remains stubbornly high and many people who would likely have a job in a stronger economy are not even looking for work. Consequently, the share of the population with a job remains well below what it was over the two decades before the recession started in December 2007 (see chart).

Some of the recent decline in labor force participation — the percentage of people 16 or older who are working or actively looking for work — reflects the aging of the population. Baby boomers are starting to retire and the share of people in their prime working years is falling. But the decline also reflects to an important extent an ongoing dearth of good job prospects. Some people retire earlier than they otherwise would or go on disability when they might be able, in a stronger job market, to find a job that accommodates their disability. Others become discouraged about their job prospects and stop looking until conditions improve. The unemployment rate doesn’t reflect those decisions; to be counted as officially unemployed a person must be actively looking for work. But many of those people would start looking for work again if they thought jobs were available.

A robust jobs recovery that both reduces unemployment and brings people back into the labor force requires much faster economic growth than we have seen over the past few years. On the monetary policy side, the Federal Reserve remains committed to accommodating faster growth without raising interest rates at least as long as the unemployment rate remains above 6½ percent and inflation remains contained. The problem is on the fiscal policy side. As the Fed’s monetary policymaking committee this week stated flatly, “fiscal policy is restraining economic growth.”

For example, lawmakers allowed the payroll tax cut to expire at the end of the year (while extending some of the high-income tax cuts that have much lower job-creating, bang-for-the-buck impacts) because they are focused too much on deficit reduction and not enough on job creation, and because many lawmakers insisted on preserving as much of the high-income tax cuts as possible. They have let sequestration’s automatic spending cuts take effect rather than crafting a balanced alternative that would achieve the same deficit reduction over the longer term without hampering the economic recovery (and ideally providing additional short-term infrastructure investment or other stimulus).

The Fed has recognized that unemployment is too high and there is no immediate threat of inflation. It’s time for lawmakers to recognize that unemployment is too high and there is no looming debt crisis. Spending money on job creation now is not incompatible with deficit reduction and debt stabilization over the longer run.

About the April Jobs Report

The April jobs report modestly exceeded expectations, but a robust jobs recovery remains elusive, especially since the full effects of sequestration have yet to be felt.

- Private and government payrolls combined rose by just 165,000 jobs in April and job growth in February and March was revised up by a total of 114,000 jobs. Private employers added 176,000 jobs in April, while government employment fell by 11,000. Federal government employment fell by 8,000, state government employment fell by 1,000, and local government employment fell by 2,000.

- This is the 38th straight month of private-sector job creation, with payrolls growing by 6.8 million jobs (a pace of 178,000 jobs a month) since February 2010; total nonfarm employment (private plus government jobs) has grown by 6.2 million jobs over the same period, or 162,000 a month. Total government jobs fell by 626,000 over this period, dominated by a loss of 428,000 local government jobs.

- Despite 38 months of private-sector job growth, there were still 2.6 million fewer jobs on nonfarm payrolls and 2.0 million fewer jobs on private payrolls in April than when the recession began in December 2007. April’s job growth would be considered solid in an economy that had already largely recovered from the recession, but it is well below the sustained job growth of 200,000 to 300,000 a month that would mark a robust jobs recovery. Job growth in the first four months of 2013 has averaged 196,000 a month, but the pace has slowed considerably over the past two months.

- The unemployment rate was 7.5 percent in April, and 11.7 million people were unemployed. In April, the unemployment rate was 6.7 percent for whites (2.3 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession), 13.2 percent for African Americans (4.2 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession), and 9.0 percent for Hispanics or Latinos (2.7 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession).

- The recession and lack of job opportunities drove many people out of the labor force. After large declines in February and March, the labor force increased in April. Yet it remains 416,000 people smaller than it was in January. The labor force participation rate (the share of people aged 16 and over who are working or actively looking for work) was 63.3 percent in April; the last time it was lower was August 1978.

- The share of the population with a job, which plummeted in the recession from 62.7 percent in December 2007 to levels last seen in the mid-1980s and has remained below 60 percent since early 2009, was 58.6 percent in April.

- The Labor Department’s most comprehensive alternative unemployment rate measure — which includes people who want to work but are discouraged from looking (those marginally attached to the labor force) and people working part time because they can’t find full-time jobs — was 13.9 percent in April. That’s down from its all-time high of 17.1 percent in late 2009 (in data that go back to 1994) but still 5.1 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession. By that measure, roughly 22 million people are unemployed or underemployed.

- Long-term unemployment remains a significant concern. Nearly two-fifths (37.4 percent) of the 11.7 million people who are unemployed — 4.4 million people — have been looking for work for 27 weeks or longer. These long-term unemployed represent 2.8 percent of the labor force. Before this recession, the previous highs for these statistics over the past six decades were 26.0 percent and 2.6 percent, respectively, in June 1983.

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities is a nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization and policy institute that conducts research and analysis on a range of government policies and programs. It is supported primarily by foundation grants.