Statement by Chad Stone, Chief Economist, on the March Employment Report

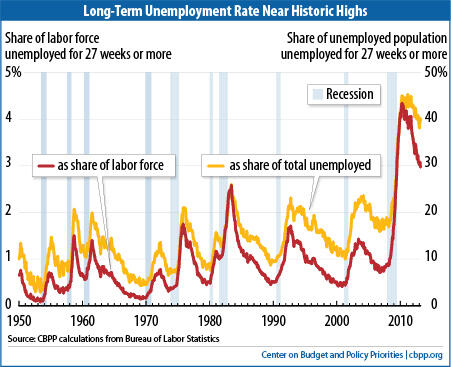

Today’s jobs report, with disappointing job growth and a large drop in the labor force, shows that a robust jobs recovery remains elusive. That situation won’t likely improve in coming months as the sequestration budget cuts begin to slow the economic recovery and make it harder for the unemployed — especially the unprecedented numbers of long-term unemployed (see chart) — to find a job. Adding insult to injury, sequestration also cuts federal unemployment insurance (UI) benefits for the long-term unemployed.

Sequestration will subtract 0.6 percentage points from economic growth in 2013, suppressing job growth by 750,000 jobs, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates. That will come on top of the drag on growth and job creation from the expiration of the payroll tax cut at the end of 2012. Due in large part to these factors, CBO expects the economy to grow only 1.4 percent in 2013 and the unemployment rate to remain above 7½ percent through next year.

Federal emergency UI provides additional weeks of unemployment compensation to people who run out of regular state UI benefits before they can find a job (typically after 26 weeks). Normally, the federal benefit is the same as the state benefit (an average of roughly $300 a week), but sequestration will reduce the federal benefit enough to generate the required budget savings over the remainder of fiscal year 2013, which ends on September 30. Sequestration also cuts federal funding for the states’ costs of administering UI and for employment and training programs that help the unemployed get back to work sooner.

Policymakers do not need to maintain sequestration to put the budget on a sustainable path — that is, a path that “stabilizes” the debt so it stops growing faster than the economy over 10 years. Consequently, policymakers should replace sequestration with a balanced set of policies that phases in deficit reduction without jeopardizing the economic recovery or imposing unnecessary hardship on the long-term unemployed and other vulnerable people. Ideally, policymakers would couple temporary new fiscal measures to accelerate growth and job creation now with permanent, phased-in deficit-reduction measures, as former Office of Management and Budget and CBO director Peter Orszag, former Federal Reserve Board Vice Chairman Alan Blinder, and other economic and budget experts have recommended.

About the March Jobs Report

The March jobs report was disappointing; payroll employment growth slowed dramatically and the drop in the unemployment rate reflected declining labor force participation.

- Private and government payrolls combined rose by just 88,000 jobs in March (although job growth in January and February was revised up by a total of 61,000 jobs). Private employers added 95,000 jobs, while government employment fell by 7,000. Federal government employment fell by 14,000 (largely due to a loss of 12,000 postal service jobs). State government employment rose by 9,000 and local government employment fell by 2,000.

- This is the 37th straight month of private-sector job creation, with payrolls growing by 6.5 million jobs (a pace of 175,000 jobs a month) since February 2010; total nonfarm employment (private plus government jobs) has grown by 5.9 million jobs over the same period, or 159,000 a month. Total government jobs fell by 605,000 over this period, dominated by a loss of 417,000 local government jobs.

- Despite 37 months of private-sector job growth, there were still 2.8 million fewer jobs on nonfarm payrolls and 2.3 million fewer jobs on private payrolls in March than when the recession began in December 2007. March’s job growth was disappointing, and we are still waiting to see sustained job growth of 200,000 to 300,000 jobs a month that would mark a robust jobs recovery. Job growth in the first three months of 2013 has averaged just 168,000 a month.

- The unemployment rate was 7.6 percent in March, and 11.7 million people were unemployed. In March, the unemployment rate was 6.7 percent for whites (2.3 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession), 13.3 percent for African Americans (4.3 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession), and 9.2 percent for Hispanics or Latinos (2.9 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession).

- The recession and lack of job opportunities drove many people out of the labor force. The labor force participation rate (the share of people aged 16 and over who are working or actively looking for work) was 63.3 percent in March; the last time it was lower was August 1978.

- The labor force shrank by 496,000 in March, with employment reported by households falling by 206,000 and unemployment falling by 290,000; falling unemployment can shrink the labor force because, if jobless people stop looking for work, they’re not officially counted as unemployed or part of the labor force. In a robust jobs recovery, both labor force participation and employment would be increasing.

- The share of the population with a job, which plummeted in the recession from 62.7 percent in December 2007 to levels last seen in the mid-1980s and has remained below 60 percent since early 2009, was 58.5 percent in March, just below its average in 2012. In a robust jobs recovery, that percentage would be rising.

- The Labor Department’s most comprehensive alternative unemployment rate measure — which includes people who want to work but are discouraged from looking (those marginally attached to the labor force) and people working part time because they can’t find full-time jobs — was 13.8 percent in March. That’s down from its all-time high of 17.1 percent in late 2009 (in data that go back to 1994) but still 5.0 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession. By that measure, roughly 22 million people are unemployed or underemployed.

- Long-term unemployment remains a significant concern. Nearly two-fifths (39.6 percent) of the 11.7 million people who are unemployed — 4.6 million people — have been looking for work for 27 weeks or longer. These long-term unemployed represent 3.0 percent of the labor force. Before this recession, the previous highs for these statistics over the past six decades were 26.0 percent and 2.6 percent, respectively, in June 1983.

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities is a nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization and policy institute that conducts research and analysis on a range of government policies and programs. It is supported primarily by foundation grants.