Statement by Chad Stone, Chief Economist, on the December Employment Report

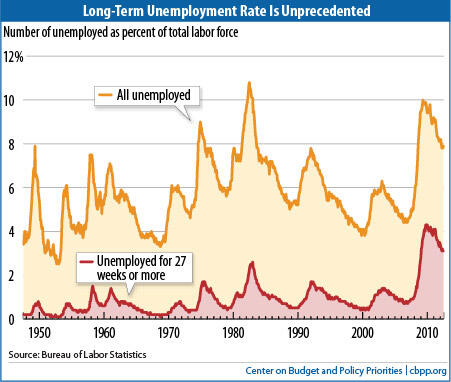

The economy added private sector jobs for the 34th straight month in December, but a robust recovery remains elusive, long-term unemployment remains very high (see chart), and threats to the economy from misguided policies in Washington remain significant.

Policymakers appropriately renewed federal emergency unemployment insurance (UI) through 2013 in this week’s budget deal, but they did not renew the payroll tax cut for another year (or enact a similar temporary income tax cut) to further boost the recovery and brighten jobless workers’ job prospects. Moreover, the looming threat of a fight over the debt ceiling and some policymakers’ insistence on large spending cuts, as well as the potential for large across-the-board budget cuts (“sequestration”) on March 1, pose further risks to the recovery and job creation.

This week’s “fiscal cliff” budget deal would have been far better for economic growth and job creation in the coming year if it had included a one-year extension of the payroll tax cut (or a similar income-tax measure). Among all of the tax cuts that were expiring at the end of 2012 as part of the fiscal cliff, only the 2009 refundable tax credits for low-income working families have a higher “bang-for-the-buck” impact.

As with the UI extension through 2013, such a tax cut would have added little to future deficits because both would be temporary. Contrast that with, as part of the budget deal, the permanent extension of an extremely generous tax break for the heirs of the nation’s largest estates, which provides essentially no boost to the economy over the next year while adding substantially to future deficits, and a permanent extension of some of the high-income Bush tax cuts — both of which have the lowest “bang-for-the-buck” impact of any expiring tax cuts in the fiscal cliff.

The budget deal also deferred sequestration for only 60 days. If it takes effect or is replaced by other immediate budget cuts, that will withdraw demand from the economy, slowing growth and job creation.

While policymakers continued UI for another year, they clearly are not doing as much as they should to promote a stronger recovery with abundant job opportunities. Despite the complaints of those opposed to the budget deal, the largest threat to the recovery comes from an insufficient boost to short-term spending and the threat of brinksmanship over raising the debt ceiling — not from the partial repeal of the high-income Bush tax cuts.

About the December Jobs Report

Job growth increased in December and the unemployment rate remained just below 8 percent as it has for the past four months. (Past unemployment and other data from the household survey have been revised to reflect new seasonal adjustment factors.).

- Private and government payrolls combined rose by 155,000 jobs in December. Private employers added 168,000 jobs, while government employment fell by 13,000. Federal employment fell by 3,000 and local government employment fell by 14,000, while state government employment rose by 4,000.

- This is the 34th straight month of private-sector job creation, with payrolls growing by 5.3 million jobs (a pace of 157,000 jobs a month) since February 2010; total nonfarm employment (private plus government jobs) has grown by 4.8 million jobs over the same period, or 141,000 a month. Total government jobs fell by 546,000 over this period, dominated by a loss of 395,000 local government jobs.

- These data do not reflect the preliminary estimate of “benchmark” revisions to the payroll jobs count that will be incorporated into the official data in February. The preliminary estimate of the revisions would raise total payroll employment in March 2012 by 386,000 jobs (0.3 percent) and private employment by 453,000 (0.4 percent), while lowering government employment by 67,000 (0.3 percent).

- Despite the 34 months of private-sector job growth, there were still 4.0 million fewer jobs on nonfarm payrolls and 3.5 million fewer jobs on private payrolls in December than when the recession began in December 2007. Job growth averaged 151,000 jobs a month in the past three months — well short of the 200,000 to 300,000 jobs a month that would mark a robust jobs recovery. (All figures exclude the preliminary revisions discussed in the previous bullet.)

- The unemployment rate stayed at 7.8 percent in December, and the number of unemployed Americans edged up to 12.2 million in revised data for the year that incorporate new seasonal adjustment factors. The unemployment rate has been between 7.8 and 7.9 percent over the past four months and the number of unemployed has been between 12.0 and 12.2 million in the new data. In December, the unemployment rate was 6.9 percent for whites (2.5 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession), 14.0 percent for African Americans (5.0 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession), and 9.6 percent for Hispanics or Latinos (3.3 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession).

- The recession and lack of job opportunities drove many people out of the labor force. The labor force participation rate (the share of people aged 16 and over who are working or actively looking for work) was 63.6 percent in December, about the same as its 63.7 percent average for the year. Prior to this year, it had not been so low since the early 1980s.

- The labor force increased by 192,000 people in December, which is an encouraging sign. However, the number of people with a job rose by just 28,000, while unemployment rose by 164,000, keeping the unemployment rate from falling with the rise in the labor force. (These numbers come from a different survey from the one used to estimate payroll job growth.)

- The share of the population with a job, which plummeted in the recession from 62.7 percent in December 2007 to levels last seen in the mid-1980s and has remained below 60 percent since early 2009, was 58.6 percent in December, the same as its average over the year.

- The Labor Department’s most comprehensive alternative unemployment rate measure — which includes people who want to work but are discouraged from looking (those marginally attached to the labor force) and people working part time because they can’t find full-time jobs — was 14.4 percent in December. That’s down from its all-time high of 17.2 percent in November 2009 (in data that go back to 1994) but still 5.6 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession. By that measure, roughly 23 million people are unemployed or underemployed.

- Long-term unemployment remains a significant concern. Almost two-fifths (39.1 percent) of the 12.2 million people who are unemployed — 4.8 million people — have been looking for work for 27 weeks or longer. These long-term unemployed represent 3.1 percent of the labor force. Before this recession, the previous highs for these statistics over the past six decades were 26.0 percent and 2.6 percent, respectively, in June 1983.

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities is a nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization and policy institute that conducts research and analysis on a range of government policies and programs. It is supported primarily by foundation grants.