Several policymakers, including Governor Mitt Romney and Senator Pat Toomey (R-PA), have proposed cutting all marginal income tax rates by the same percentage. Further, Senators Hatch and McConnell have proposed that instructions to Congress for tax reform include a requirement that individual tax rates be reduced “proportionally.” While one might assume that such uniform, across-the-board cuts benefit all taxpayers equally, the reality is that they disproportionately benefit higher-income people, raising their after-tax incomes by much larger percentages than less-affluent people. They also can be extremely costly, thereby placing an added load on other potential contributors to deficit reduction. Moreover, the proposed rate cuts would be in addition to extending President Bush’s tax cuts, which are themselves both costly and skewed to high-income people.[1]

At a time when tax policy should be seeking to reduce deficits and push against rising income inequality, across-the-board tax cuts do the exact opposite. Thus they are a particularly poor place to start when formulating tax reform or deficit reduction plans.[2]

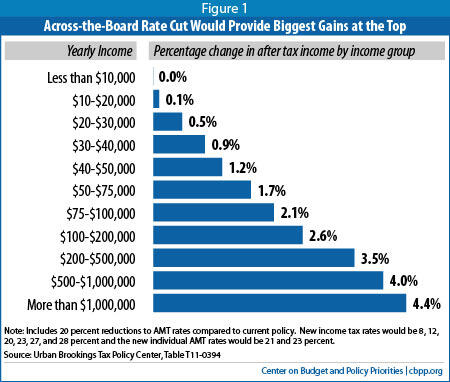

Table 1

Across-the-Board Rate Cut Would Provide Biggest Gains at the Top |

Cash Income Level

(thousands of 2011 dollars) | Change in after-tax income | Average federal tax cut |

| Less than 10 | 0.0% | $0 |

| 10-20 | 0.1% | -$19 |

| 20-30 | 0.5% | -$123 |

| 30-40 | 0.9% | -$294 |

| 40-50 | 1.2% | -$507 |

| 50-75 | 1.7% | -$919 |

| 75-100 | 2.1% | -$1,582 |

| 100-200 | 2.6% | -$2,981 |

| 200-500 | 3.5% | -$7,940 |

| 500-1,000 | 4.0% | -$21,359 |

| More than 1,000 | 4.4% | -$92,400 |

| All | 2.5% | -$1,591 |

Note: Compared to current policy. Includes 20 percent reductions to income tax and AMT rates. New income tax rates would be 8, 12, 20, 23, 27 and 28 percent; new individual AMT rates would be 21 and 23 percent.

Source: Urban Brookings Tax Policy Center, Table T11-0394 |

Economists generally agree that the best measure of whether a tax change is progressive or regressive is the percent by which it changes the after tax-incomes of various income groups. Across-the-board rate cuts raise after-tax incomes by a larger percentage for those at the top of the income scale than for those at the middle and bottom, meaning they are regressive. (Cutting all rates by the same number of percentage points, rather than the same percentage, is also regressive.)

To understand why cutting rates by an equal percentage produces unequal results, consider a simple tax system with two rates: 20 percent and 40 percent. Assume that both tax rates are reduced by 50 percent, so that the new bottom rate is 10 percent and the new top rate is 20 percent. These rate cuts enable taxpayers to keep 90 cents — rather than 80 cents — of each dollar taxed at the bottom rate, generating a 12.5 percent increase in after-tax income. [3] But, for each dollar taxed at the top rate, taxpayers will keep 80 cents, rather than 60 cents, generating a 33 percent increase in after-tax income.[4]

Thus, even though both tax rates fall by the same percentage, the result is a regressive tax cut that benefits people in the top bracket the most, not only in dollars but in the percentage increase in their after-tax income.

- Low-income taxpayers who have all of their income taxed at the bottom rate will get a 12.5 percent increase in their after-tax income.

- For taxpayers with incomes high enough to face the higher tax rate, the percentage increase in their after-tax income will be somewhere between 12.5 and 33 percent: they will take home 12.5 percent more of their income taxed in the lower bracket and 33 percent more of their income taxed in the higher bracket. The more income they have taxed at the higher rate, the closer their total increase in after-tax income will be to 33 percent.

The same principle holds for tax codes with more than two rates, like the federal income tax code. Higher-income taxpayers, who face the top tax rates, would receive a bigger percentage boost in after-tax income from across-the-board marginal income tax rate cuts than low-and moderate-income taxpayers, who face only the lower tax rates.

Estimates from the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center (TPC) starkly illustrate this. (See Figure 1.) A 20 percent cut to all current marginal income tax and AMT rates[5] would raise average after-tax incomes by 4.4 percent among millionaires but by only 1.7 percent among taxpayers with incomes between $50,000 and $75,000. As Table 1 shows, these percentages work out to average tax cuts of $92,400 for millionaires and $919 for middle-income taxpayers.