- Home

- Chart Book: 10 Things You Need To Know A...

Chart Book: 10 Things You Need to Know About the Capital Gains Tax

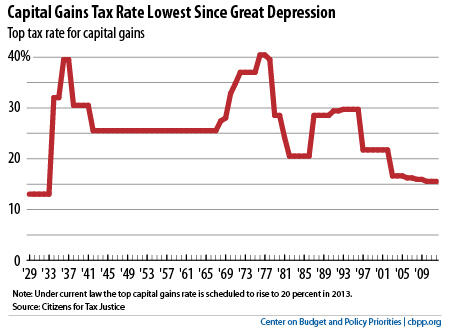

1. Capital gains tax rates are the lowest since the Great Depression.

The capital gains tax rate on assets that have been held for more than one year is 15 percent for people above the 15 percent income tax bracket. (People in or below the 15 percent bracket owe no capital gains tax.) This is far below the top marginal tax rate on ordinary income — currently 35 percent — and is the lowest rate on long-term capital gains since the Great Depression.

The capital gains rate will remain well below the top rate on salary and wages even if tax rates rise in 2013 as scheduled. Under current law, the rate on long-term capital gains will rise from 15 to 20 percent and a 3.8 percent surtax on capital gains and other net investment income over $250,000 (for a married couple filing jointly) will take effect. But the top marginal income tax rate will also rise, to 39.6 percent.

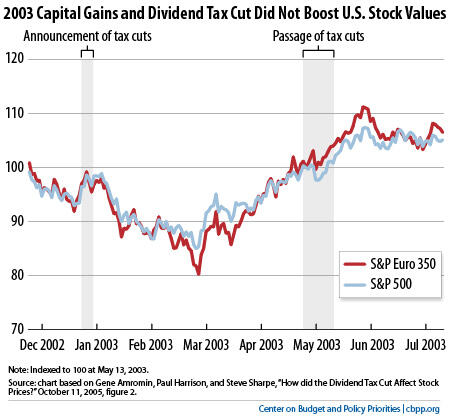

2. There’s no evidence that low capital gains tax rates boost the stock market, investment, or the economy.

There is no sound evidence that cutting capital gains taxes to levels far lower than ordinary income tax rates contributes to economic growth at all — let alone enough to outweigh the significant economic cost of doing so.

- Federal Reserve economists concluded in 2005 that the capital gains and dividend tax cut in 2003 had little effect on the stock market. European and U.S. stocks moved together, both after the announcement of the U.S. tax cut and after the tax cut itself (see chart below). If the tax cut had boosted U.S. stocks, U.S. stocks should have performed better relative to European stocks, but they did not. As the Wall Street Journal stated, the study “concludes that the tax cut … was a dud when it came to boosting the stock market.”

- “[T]here is no evidence that links aggregate economic performance to capital gains tax rates,” according to University of Michigan tax economist Professor Joel Slemrod.

- The Congressional Research Service (CRS) found no statistically significant correlation between the top capital gains or marginal income tax rates since 1945 and: (1) private saving; (2) investment; (3) growth in labor productivity; or (4) growth in real per capita GDP. That’s not proof that cutting capital gains or income tax rates has no economic effect; things happening in the economy other than changes to the capital gains tax rates could have obscured any such effects. But it suggests that cutting capital gains tax rates doesn’t have a massive and positive effect on the economy.

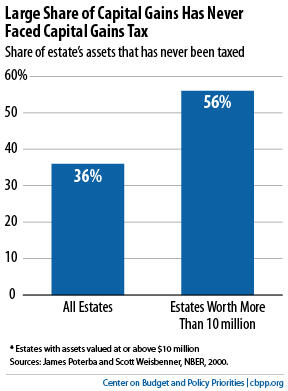

3. A large share of capital gains is never subject to capital gains tax.

About half of all capital gains are never subject to capital gains tax, according to CRS economist Jane Gravelle.

One major reason is that the capital gains tax is forgiven at death, so if a taxpayer holds on to an asset until he or she dies, neither the taxpayer’s estate nor the heirs will ever pay tax on any increase in the asset’s value prior to the taxpayer’s death. As this chart shows, unrealized capital gains (i.e., capital gains that have not been “cashed in”) make up an estimated 36 percent of the value of all estates and 56 percent of the value of estates worth more than $10 million.

Moreover, estates worth less than $5 million per person ($10 million per couple) are exempt from the estate tax, so their unrealized capital gains will face neither capital gains tax nor estate tax.

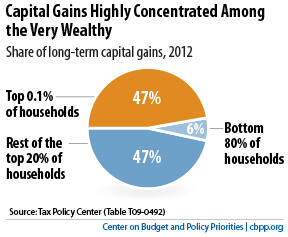

4. Capital gains are highly concentrated at the top.

As this chart shows, the top one-tenth of 1 percent of taxpayers will receive 47 percent of all capital gains in 2012, according to the Tax Policy Center. (The top 1 percent of taxpayers will receive 71 percent of all capital gains.) Meanwhile, the bottom 80 percent of filers will receive only 10 percent of all capital gains.

Even more striking, the latest IRS data show that in 2008, 12 percent of all capital gains went to the 400 highest-income taxpayers, whose adjusted gross incomes average roughly $202 million each.

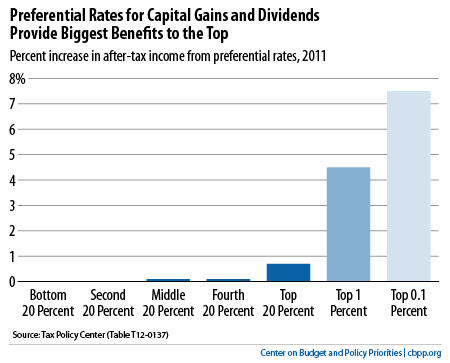

5. The benefits of preferential tax rates for capital gains and dividends go overwhelmingly to the highest-income taxpayers.

Because capital gains are so highly concentrated at the top of the income scale, the preferential rates for capital gains are highly regressive: they raise after-tax incomes by much more among very high-income taxpayers than among low- and moderate-income taxpayers.

As this chart shows, TPC estimates that, in 2011, the preferential rates raised after-tax incomes by 7.5 percent (an average of $356,750) among the top 0.1 percent of taxpayers but by just 0.1 percent (an average of $23) among the middle fifth of households.

These figures reflect only the benefits of the preferential rates, not the various other tax preferences that capital gains enjoy (such as the exclusion of many capital gains from capital gains taxation altogether, as the second chart shows).

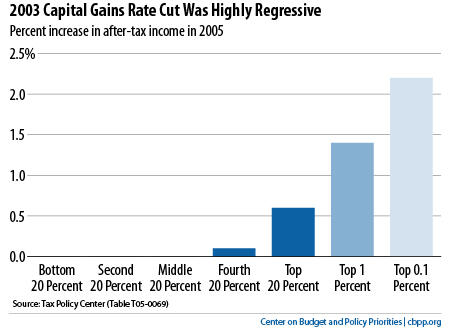

6. The 2003 cut in the capital gains rate cut was highly regressive.

Policymakers lowered the capital gains rate from 20 percent to 15 percent in 2003. As this figure shows, TPC estimates that in 2005, that tax cut alone raised after-tax incomes by 2.2 percent (about $75,800 on average) among the top 0.1 percent of filers but by just 0.03 percent (about $10) among the middle 20 percent of filers.

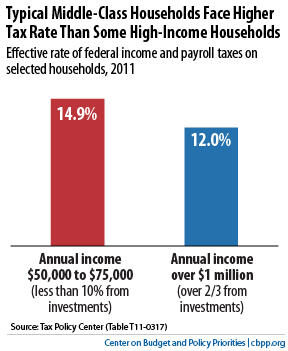

7. The capital gains tax preference is a major reason why the tax code violates the Buffett rule.

The preferential rate for capital gains is a key reason why the tax system violates the “Buffett rule,” which essentially states that high-income taxpayers should not pay less of their incomes in federal taxes than middle-income Americans. A significant group of high-income taxpayers — particularly those who derive the bulk of their income from capital investments — pay taxes at a lower rate than many middle-class families.

As this chart shows, households with incomes between $50,000 and $75,000 who receive most of their income from their paychecks (as middle-class people generally do) paid 14.9 percent of their income in federal income and payroll taxes in 2011, according to TPC. Millionaires who received more than a third of their income from capital gains and qualified dividends faced a 14.6 percent effective tax rate, and millionaires who derived more than two-thirds of their income from these sources faced a 12.0 percent rate.

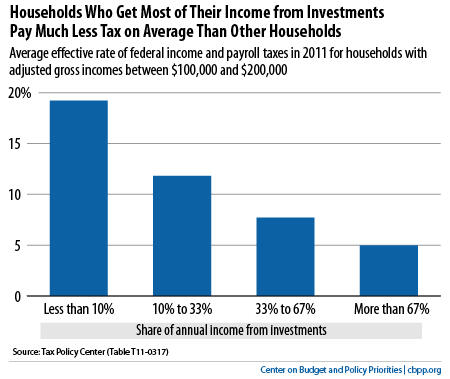

8. Tax preferences for capital gains are inequitable.

The tax breaks for capital gains are not only regressive, but unfair in another way. Two families who have the same amount of income and are otherwise similar in their expenses and family situations may end up paying vastly different amounts of tax depending on whether they generate most of their income from wages and salaries or from tax-preferred investments.

For example, as the graph shows, households with incomes between $100,000 and $200,000 who get more than two-thirds of their income from investments taxed at the preferential rates owe an average of 5 percent of their incomes in tax. That’s only around a quarter of the 19.2 percent rate faced by households earning the same income but who get less than 10 percent of it from these sources.

9. Tax preferences for capital gains are costly.

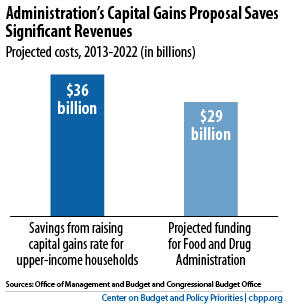

The preferential tax treatment of capital gains adds billions of dollars to deficits. Even small steps to minimize it could contribute significantly to deficit reduction.

Letting the capital gains rate return in 2013 to 20 percent for couples with adjusted gross incomes over $250,000 ($200,000 for single filers), as the Administration has proposed, would save about $36 billion over ten years. That’s more than the projected budget for the Food and Drug Administration over the same ten years.

If policymakers enact comprehensive tax reform, they should consider much more substantial change in this area.

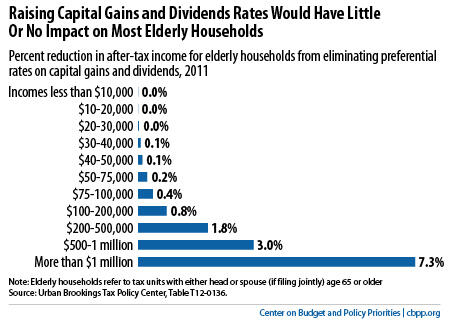

10. Raising Capital Gains and Dividend Rates Would Have Little or No Impact on Most Elderly Households

Some argue that reducing the tax preferences for capital gains would hurt the elderly, noting that elderly households are more likely to have some capital gains or dividend income than younger households. But among the elderly — as among the population as a whole — capital gains and dividend income is highly concentrated among a small group of high-income households. Any implication that raising dividends and capital gains rates would significantly affect more than a small minority of seniors would be misleading.

Most elderly households receive little benefit from the lower tax rates for capital gains and dividends and would face little if any tax increase if those rates were raised. TPC figures show:

- Nearly 60 percent of elderly filers had incomes below $40,000 in 2011. Taxing capital gains and dividends at the same rates as salary and wages would have reduced their after-tax incomes by much less than one-tenth of 1 percent, on average — or less than $6. (See chart.)

- For the 21 percent of elderly households with incomes between $50,000 and $100,000, taxing capital gains and dividends at the same rates as salary and wages in 2011 would have reduced their after-tax incomes by less than one-third of 1 percent, on average — or $195.

- Nearly all elderly households (96 percent) had incomes below $200,000 in 2011. The Administration’s proposal to allow the capital gains rate to rise modestly for upper-income households wouldn’t affect these households at all.

For more information, see this CBPP report: "Raising Today’s Low Capital Gains Tax Rates Could Promote Economic Efficiency and Fairness, While Helping Reduce Deficits."