- Home

- Testimony Of LaDonna Pavetti, Ph.D. Vice...

Testimony of LaDonna Pavetti, Ph.D. Vice President, Family Income Support Policy, Before the House Ways and Means Committee, Subcommittee on Human Resources, Hearing on "State TANF Spending and its Impact on Work Requirements"

Good afternoon Chairman Davis, Ranking Member Doggett, and distinguished members of the Subcommittee. Thank you for inviting me to testify on the relationship between TANF State maintenance-of-effort (MOE) requirements and their interaction with work requirements.

I am Vice President for Family Income Support Policy at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Prior to coming to the Center two and a half years ago, I spent 16 years studying welfare programs, including the implementation of welfare reform since its inception. I have done significant work documenting how states have implemented TANF work requirements, including how they responded to the changes enacted through the Deficit Reduction Act (DRA) of 2005.

After providing some background on the topic of today's hearing, I will focus my testimony on three key points:

- First, excess MOE, which states have used to help meet their TANF Work Participation Requirement (WPR), is a symptom of a much larger problem – the failure of the TANF WPR to adequately measure states' commitment to and success in helping TANF recipients, most of whom are single mothers, find and maintain employment.

- Second, two key problems related to MOE – third-party non-governmental MOE spending and the 100 percent MOE requirement required to access the Contingency Fund — are unrelated to TANF work requirements, but also are important to address.

- Finally, the erosion of the TANF block grant and cuts in TANF and other human service funding are making it increasingly difficult for states to help unemployed individuals find work and to provide a safety net for those unable to work. Expectations for states need to be consistent with what they can do with the resources they have available.

Background

Congress established the TANF Work Participation Rate (WPR) as part of the 1996 welfare law to ensure that states focus their cash assistance programs on helping recipients obtain work. The WPR measures the share of a state's TANF households containing a "work-eligible individual" who participates in assigned work activities for the required number of hours (20 per week for families with a child under age 6 and 30 per week for everyone else). The rate is driven by its two components: (1) the number of TANF recipients who meet their work participation requirement and (2) the number of families served in the state's TANF program. While there is some variation in how states structure their work programs, there is far more variation in who is served by TANF in the first place.

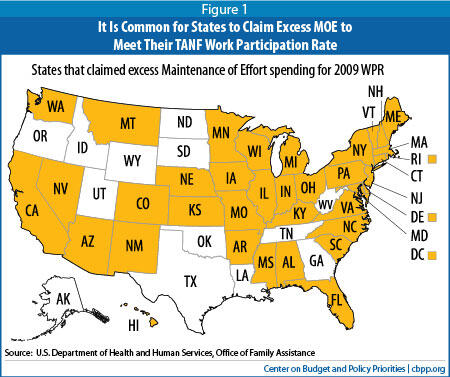

States are required to meet a 50 percent WPR for all families and a 90 percent WPR for two-parent families, but they can lower that target work rate by earning a "caseload reduction credit." This credit can come from two sources: (1) reducing the state's TANF caseload below its 2005 level and (2) "excess MOE," or spending more state dollars on TANF-related services than the program's MOE requirement stipulates.[1] (The Department of Health and Human Services has devised a formula that it uses to translate the excess MOE into the number of cases by which the state can lower its current caseload. This reduced caseload is then compared to the state's 2005 caseload for purposes of determining how much the caseload has "declined" since 2005.) A state's WPR is reduced one percentage point for each percentage-point decline in its caseload below the 2005 level.

The caseload reduction credit was a response to a flaw in the WPR. Without the caseload reduction credit, states that kept working recipients on the caseload would have been rewarded while those that helped people leave welfare through work would have been penalized. The idea behind providing states with credit for spending more than was required was that states should not be penalized for serving additional families with non-required funds.

Unfortunately, neither has ever worked as intended.

- States that reduce their caseloads below their 2005 level get credit regardless of whether the recipients who leave TANF find employment. Studies conducted in the early years of welfare reform found that only about half of the recipients who left the TANF rolls did so for work.[2] Although more recent data are not available, we know from recent national studies that the number of families living in extreme poverty has increased, largely because TANF serves substantially fewer families now than at the start of welfare reform.[3]

- Similarly, it appears that some states that claim excess MOE have done so not by increasing their state contributions to activities designed to help TANF recipients find and maintain work or by serving more recipients, but instead by claiming existing (but previously unreported) governmental and third-party, non-governmental spending that meets one of TANF's four purposes as MOE spending.

Excess MOE Issue Largely Reflects Flaws in Work Participation Rate

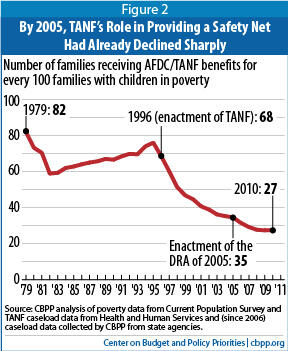

While states have had the option of claiming excess MOE to help meet their WPR since 1999, they did not begin to adopt the strategy until after the passage of the Deficit Reduction Act (DRA) of 2005. The DRA changed the comparison year for the caseload reduction credit from 1995 to 2005, expanded the TANF cases subject to the work requirement and instructed HHS to develop standardized definitions for work activities. These changes made the WPR harder for states to meet and further exposed its flaws as a performance measure. By 2005, states had already reduced their TANF caseloads far below where they were at the start of welfare reform – and employment among single mothers was already substantially above employment for married mothers and single women without children. In 2005, for every 100 families in poverty, states served just 35 families in their TANF programs, down from 68 families in 1996. (See Figure 2.)

Thus, the problem we need to address first and foremost is the failed design of the WPR. If the WPR were replaced with a new performance measure that captures employment outcomes, the excess MOE issues related to meeting the WPR would disappear.

Work Participation Rate Fails to Measure Success in Increasing Employment

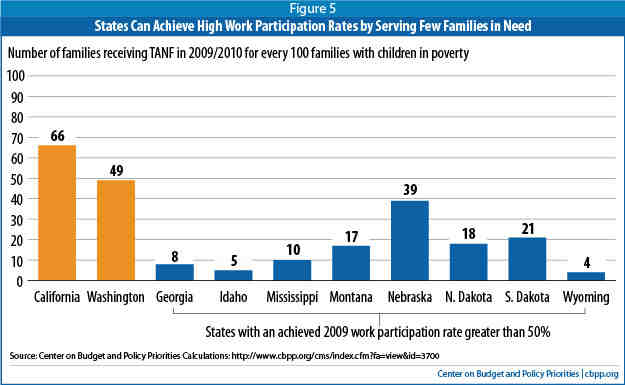

In fiscal year 2009, eight states — Georgia, Idaho, Mississippi, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wyoming – achieved a work participation rate of 50 percent or more, so they met the WPR target without needing any caseload reduction credit (either from reducing their TANF caseload or from claiming excess MOE). These states are held up as models that the WPR is achievable. It is notable that, except for Georgia, these states are all small, very rural states with small TANF caseloads.

The important question, however, is whether these states are models of what we actually want a TANF program to achieve. In other words, are states that achieve a high work rate effective in helping low-income single mothers succeed in the labor market? Do they provide an adequate safety net to the most disadvantaged? To try to answer these questions, I suggest looking at three different measures: (1) the share of single mothers (whether or not they are on TANF) who are employed; (2) the ratio of the number of TANF recipients engaged in work activities to the number of unemployed single mothers in the state; and (3) the ratio of the number of TANF cases to the number of families in poverty.

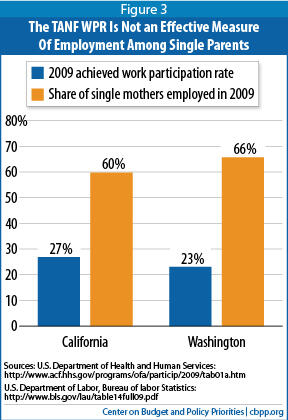

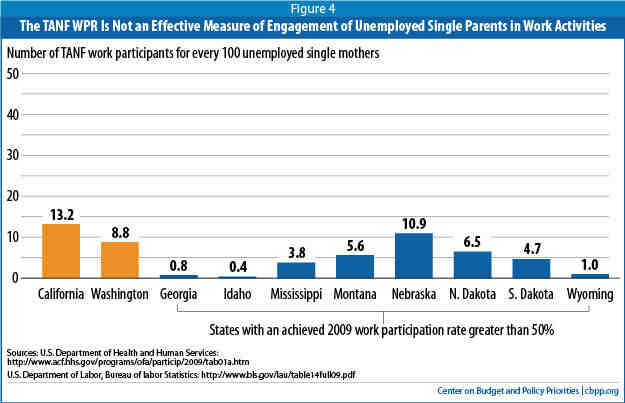

By these measures, this group of states does not stand out. Comparing them to two much larger states that achieved far lower work participation rates — Washington State and California — shows that the WPR fails to adequately measure whether states are meeting the primary goal of welfare reform: increasing employment while providing a safety net for families unable to work.

- Washington State. Washington State has done quite well at getting single mothers into the labor force, even during hard economic times: in fiscal year 2009, despite the state's high overall unemployment rate (8.9 percent on average), two-thirds of single mothers were employed – a higher employment rate than in 38 of the 50 states. (See Figure 3.) Among the eight states listed above that achieved a WPR of 50 percent or more, only three had a higher employment rate among single mothers — and all three had much lower overall unemployment rate and are significantly smaller states. Moreover, in an analysis of employment among TANF recipients in fiscal year 2007, the state found that 61 percent were employed during that year.Yet Washington State's performance on the WPR does not paint the same picture of success. In 2009, the state achieved a WPR of 23 percent, meaning that about one-quarter of its TANF cases with a "work-eligible individual" participated in approved work activities for the required number of hours. Without the help of a substantial caseload reduction credit, based in part on an excess MOE claim, Washington State would not have met its WPR.Image

- California. Like Washington, California achieved a relatively low WPR in 2009: 26.8 percent. In fact, California was one of five states that failed to meet the WPR target even with the caseload reduction credit it received.

Yet the state's low WPR obscures its demonstrated success at engaging single mothers in work activities and getting them employed. Even with a statewide unemployment rate of 11.4 percent, in 2009, fully 60 percent of single mothers in California were employed. In 2009, California engaged almost 90,000 TANF recipients in work activities for sufficient hours to meet the work participation standard, an increase of about 40,000 recipients since 2005. In the states that achieved a work rate of 50 percent or more, only Mississippi showed an appreciable increase in the number of recipients meeting the work participation standard between 2005 and 2009. In Georgia, the number of recipients meeting the work participation standard declined by more than 75 percent, from 7,303 to 1,620.

Even more telling, for every 100 single mothers in California who were unemployed in 2009, there were ten TANF recipients who met their TANF work requirement. This ratio was the second highest in the country. Among the eight states that met their WPR without relying on the caseload reduction credit, only Nebraska had a ratio anywhere close to California's. (See Figure 4.)

The example of Mississippi, the state with the highest achieved work rate, shows the other side of the story: some states achieved high WPRs despite having relatively low employment rates among single mothers. Mississippi achieved a WPR of 61 percent in 2009, but its employment rate among single mothers (56.7 percent) was among the ten lowest in the country. For every 100 unemployed single mothers, there were just four TANF cases that met their work requirement. Moreover, Mississippi achieved its high work participation rate, at least in part, by serving very few needy families in its TANF program. In 2009, for every 100 Mississippi families in poverty, only ten received cash assistance from TANF, far below the TANF-to-poverty ratios for the country as a whole (27) and for California and Washington State (66 and 49, respectively).

Not just in Mississippi, but in all eight states that achieved a WPR of 50 percent or more, TANF provides a very weak safety net for families in need. (See Figure 5.) Georgia, the only large state in this group, serves just eight families in its TANF program for every 100 in poverty, down from 82 at the start of welfare reform. This weakening of the cash safety net for families has contributed to significant increases in the number of children living in deeply poor families and has removed the safety net from the families with the greatest needs — those that have physical or mental health issues and those caring for a sick or disabled child. These families are among the most vulnerable and also have the most to gain from the services that TANF is supposed to provide.

Biggest MOE Problems Are Unrelated to the Work Participation Rate

Third-Party Non-Governmental Spending

The most significant problem associated with MOE is not directly related to the use of excess MOE to meet the WPR. Instead, it concerns what spending states count as MOE, whether to meet their regular MOE requirement or to report as excess MOE. In particular, states have combed their budgets for state expenditures that meet one of the four purposes of TANF that they can claim as MOE. In addition, they have found ways to withdraw a significant amount of state funds from programs and services that had been supported with TANF or MOE funds and still meet their MOE requirement by identifying "third-party" (i.e., non-governmental) MOE, such as spending by food banks or domestic violence shelters on TANF-eligible families.

States' increasing aggressiveness in claiming existing governmental or third-party spending as MOE is the main reason why total MOE claimed by states, which remained fairly consistent at $10-$11 billion per year in TANF's early years, rose to more than $15 billion by 2009. A number of states have reported spending substantially more than the minimum MOE required in recent years.

The practice of using third-party MOE is not limited to states that report excess MOE expenditures. Some states have identified significant existing state or third-party spending and have used this spending simply to meet — not to exceed — their MOE requirement.

A state that withdraws TANF/MOE money from various programs and identifies other state spending or third-party spending as MOE might appear to be holding TANF/MOE spending steady or even increasing it, though in reality it has significantly reduced TANF programs and services. One dramatic example comes from Georgia, where third-party MOE now represents nearly half of the MOE reported by the state, an increase of 20 percent since 2010, during the same period that the state has cut spending on other TANF-related benefits and services.[4]

Congress clearly did not intend to allow states to spend less on services for needy families than they did before TANF's creation by using third-party spending to replace state spending. This practice should be stopped.

Third-party spending in and of itself is not always problematic. For example, under the now-expired TANF Emergency Fund, states could be reimbursed for 80 percent of the costs of new spending on a narrow set of recession-related expenses. Since the state fiscal crisis sometimes made it difficult for states to come up with the 20 percent match required to access the funds, states used third-party contributions to help them meet that match, including in-kind donations from food banks, employer supervision of subsidized employees, and cash contributions from private foundations. Because states had to increase total spending compared to just before the recession, they could not use the third-party contributions to replace existing spending. This type of third-party spending contributed to the success of the Emergency Fund and should be permitted in similar circumstances.

Excess MOE and the TANF Contingency Fund

While this hearing is primarily focused on the relationship between excess MOE and work participation requirements, the MOE issue is also relevant for the Contingency Fund. Under current law, a state can access the TANF Contingency Fund if it meets a monthly economic hardship ("needy state") trigger and an MOE requirement (described below) that is more stringent than the regular TANF MOE requirement. A state that qualifies for an entire year can receive an amount worth up to 20 percent of its annual block grant and can spend Contingency Funds for any TANF purpose, though it must spend the funds during the fiscal year for which they are awarded.

Even when all states met the "needy state" economic hardship trigger during the recent recession, however, fewer than half drew on the Contingency Fund because the fund's requirements are complicated and daunting.

- To qualify for the Contingency Fund, states must spend 100 percent of their historic spending on Aid to Families with Dependent Children, a higher threshold than the regular TANF MOE requirement (which is 75 or 80 percent of historic spending, depending on whether a state met its WPR for the year). Moreover, some spending that can count toward the regular TANF MOE requirement, notably child care spending, cannot count toward the Contingency Fund MOE requirement.

- A state must not only meet the 100 percent MOE standard but also exceed it by an amount that at least matches the amount of Contingency Funds received. States that fail to do so may need to repay some of the funds received.

When queried on why they were not accessing the Contingency Fund, a number of states said they were unable or unwilling to take funding that they might need to repay. The complexity and arbitrariness of these requirements have resulted in uneven access to the fund.

Moreover, while it is reasonable to require states that receive extra federal funding to maintain at least their past level of effort, the current formula does not actually do that. Instead, a state can reduce its spending in programs that provide benefits and services to needy families and offset this decline by becoming more aggressive about identifying funding to count as MOE — whether state or local government spending or third-party spending. For example, some states in recent years have identified third-party spending in local communities in order to exceed the 100 percent MOE standard and thereby qualify for the Contingency Fund even as they cut state TANF spending.

Now is an appropriate time for policymakers to redesign the Contingency Fund to address this problem. States continue to face high unemployment, and the Contingency Fund was intended to help states during times like these. A redesign should target the uses of the fund more narrowly (such as on subsidized employment) so that states use it to address increased need directly related to a weak economy. In order to receive Contingency Funds, states should also be required to increase their spending, much as they were required to do to receive funds from the TANF Emergency Fund.

Finally, any redesign should include a simpler and updated economic hardship trigger. The current triggers are an increased SNAP (food stamp) caseload relative to the mid-1990s or increased unemployment relative to recent prior years; the former is outdated and the latter penalizes states that experience a prolonged period of high (but not increasing) unemployment, even though they are the states with the greatest need. Currently, nearly every state that meets the "needy state" criteria does so only because of its increased SNAP caseload.

The Limits of TANF Funding

Providing a safety net that focuses on helping recipients to find and maintain work requires substantial resources – it costs substantially more to cover the costs of child care and transportation for TANF recipients to meet their work requirement than it costs to provide a monthly cash grant. Inadequate and declining funding for TANF, funding threats to other programs that states rely on to help TANF recipients and other low-income families (such as the Social Services Block Grant), and significant state budget shortfalls have heightened the difficulties states are already facing in providing a safety net and employment assistance to families in need.

When it was created in 1996, the federal TANF block grant was funded at $16.5 billion per year. It has remained at that level ever since. Because it was never adjusted for inflation, federal block grant funding has lost significant value over time; states now receive 30 percent less in real (inflation-adjusted) dollars than in 1997, a year when the unemployment rate averaged 4.9 percent. The amount of state funds that states must spend to meet their MOE obligation has also remained flat since 1996, so required MOE spending levels have shrunk by 30 percent in real terms, as well.

The situation is even worse for the 17 states that previously received Supplemental Grants. Those states saw their federal TANF funds reduced by as much as 10 percent this year. The Supplemental Grants were intended, in part, to address the disadvantage that poorer states and states with high population growth would have when fixed funding is based on historical spending patterns rather than current population circumstances (but the originally designated states were never added to during the last 15 years). Now, nothing in the TANF funding formula addresses the growth in population.

The erosion and loss of TANF funds has had a pronounced impact on low-income families:

- TANF benefit levels now cover a smaller share of recipients' basic needs. The majority of states have increased their TANF benefit levels in nominal terms since the advent of the block grant, but not by enough to keep pace with inflation. When adjusted for inflation, benefit levels — which already were well below the poverty line in every state — have declined by 20 percent or more in 30 states since 1996. In the median state, the entire monthly TANF benefit equals only half of the cost of the fair market rent for a two-bedroom apartment;[5] this is HUD's basic measure of the rental cost of a modest apartment and is the rental standard used in federal low-income housing programs.

- Employment assistance counselors carry higher caseloads and consequently cannot provide as much help to people looking for work. In addition to providing cash benefits, one of the core services that TANF agencies offer is employment assistance. But because staff salaries have necessarily risen as prices have increased, while block grant funding has remained frozen, TANF staffs have been cut even as need has increased, and counselors who provide employment assistance now generally carry larger caseloads than they did prior to the recession. As a result, recipients get less help with finding employment at the very time they need more assistance because of the shortage of jobs.

- TANF-funded assistance provided to working families is weakening. The majority of parents who leave welfare for employment earn low wages. Most states provide some supportive services, especially child care and transportation assistance, to help offset some of the costs of working that these families face. But these work-related costs increase over time, whereas states' TANF funding is frozen. As a result, the amount of TANF money spent on child care for TANF recipients and low-income working families has remained flat since fiscal year 2000, even though the cost of child care has increased considerably, rising twice as fast since 2000 as the median household income of families with children.[6] When costs rise and funding remains flat, either families receive less assistance to offset the costs of working or fewer families receive assistance.

States are not in a position to make up for declining funds. In recent years, states have made broad and deep spending cuts to address the nearly $600 billion in budget gaps they have faced during the economic slump. The cuts have affected all major areas of state budgets — elementary and secondary education, health care, higher education, and human services. In 2011, states implemented some of the harshest cuts in recent history for TANF recipients. A number of states cut cash assistance deeply for families that already live far below the poverty line, ended it entirely for many other families with physical or mental health issues or other challenges, or cut child care or other work-related assistance that make it harder for many poor parents fortunate enough to have jobs to keep them.

These cuts are being made at a time when the need for assistance is great. Unemployment remains very high and the prospects of finding jobs, especially for people with low skills, are poor. Last month, unemployment was 8.1 percent. Over two-fifths (41.3 percent) of the 12.5 million people who are unemployed — 5.1 million people — have been looking for work for 27 weeks or longer.[7]

Recommendations

The focus of this hearing is on the interaction of Sate TANF MOE spending and the TANF work participation requirements, but these issues cannot be addressed without considering the larger context. Facing significant budget shortfalls, states are not in a position to significantly increase their funding for programs for needy families. That means they need to make the best possible use of the funds they have available.

The first place to look for solutions that will allow states to do this is in the design of the WPR. Eliminating the option for states to use excess MOE to help them meet their WPR will exacerbate, not solve, the problems states have encountered in trying to meet the WPR. It is very likely that states would respond to such a change by serving even fewer families in their TANF program – and would choose to serve only those that demonstrate that they are able to meet the stringent requirements, leaving even more vulnerable families without a safety net. This strategy may result in better WPRs, but it will not result in better outcomes for families – or for society as a whole.

Excess MOE is not the problem in need of a solution. It is the ineffective WPR that is in desperate need of repair – or replacement. Under the current WPR structure, states feel compelled to provide employment services to everyone, including those families they expect will leave for employment in just a short period of time. That leaves states with fewer resources to address the employment preparation needs of the families with the most significant barriers to employment. The TANF caseload today is different than the TANF caseload in 1996. The majority of single mothers nationwide are now working. To continue to make progress, we need to develop alternative pathways to work that address the needs of the single mothers who have been left behind.

Complete reconsideration of the WPR should be central to any TANF reauthorization discussions. In the interim, I offer five recommended changes that could be implemented within the current TANF structure as a part of an extension of the existing program:

- Revise the Work Participation Rate to allow states to count recipients who leave TANF for work in their WPR for 12 months. The caseload reduction credit gives states no incentive to move TANF recipients into paid employment (as opposed to merely moving them off of TANF) and encourages states to serve fewer and fewer families in need. One short-term remedy is to allow states to include recipients that find employment and leave the TANF rolls to count in their WPR for 12 months after they leave TANF rolls. This would recognize that the primary goal of TANF work programs is to help recipients find employment that eliminates or reduces the need for cash assistance. Allowing states to count for an extended period those recipients who leave for employment would give states an incentive to place recipients in jobs that will last or to provide assistance to help them stay employed.

- Instruct HHS to initiate a demonstration project that encourages states to develop alternative performance measures that focus on employment outcomes. There is near-universal agreement that the TANF Work Participation Rate is a flawed measure of state performance. However, we do not have an adequate knowledge base on which to decide what a new, more appropriate outcome measure should be, and we know that outcome measures can have perverse consequences, discouraging programs from serving the most disadvantaged families. A way to move forward is to allow states to propose, experiment with, and report on outcomes based on alternative measures that measure their success at increasing employment among TANF-eligible families while also providing a safety net to those in need.

- Restrict MOE to government spending by eliminating third-party spending, with possible exceptions only for new initiatives that require new spending for narrowly-defined purposes. Some states are increasingly relying on third-party spending to meet their MOE obligation. This is clearly contrary to the intent of the MOE requirement and should be ended, with the possible exception of continuing third-party MOE that is directly related to a new spending for narrowly defined purposes. Any restrictions on or eliminating excess MOE altogether (not just third-party) should only be considered in the context of revisiting the work rate in its entirety, including what role, if any the caseload reduction credit should play in any new approach to measuring state performance and progress.

- Redesign the TANF Contingency Fund. A number of changes are needed to make the Contingency Fund more effective. Most notably, states should be required to increase their spending in order to qualify for the fund and should be required to use the funds to address increased need directly related to a weak economy, such as providing subsidized employment opportunities to unemployed parents. At a minimum, states should be permitted to count child care spending toward the Contingency Fund MOE, as they can toward the regular TANF MOE. Also, the unemployment component of the "needy state" trigger should be redesigned so that states with continued high unemployment rates can qualify. The time to redesign the Contingency Fund is now, when it can provide much-needed help to low-income families who have been hit by the economic downturn and have not been able to find employment.

- Restore funding for the Supplemental Grants. The loss of the Supplemental Grants dealt an especially harsh blow to the 17 states that had received them since 1996, reducing their overall federal TANF funding by as much as 10 percent. The states that received this funding are poorer states with substantial numbers of families living in poverty and deep poverty. They cannot be expected to provide the same level of assistance with less funding, especially when state budgets have been hard hit by the economic downturn.

End Notes

[1] This provision is allowed under a 1999 regulation.

[2] Gregory Acs and Pamela J. Loprest, TANF Caseload Composition and Leavers Synthesis Report. Washington, D.C.: The Urban Institute, March 28, 2007, http://www.urban.org/publications/411553.html.

[3] H. Luke Shaefer and Kathryn Edin, Extreme Poverty in the United States. National Poverty Center Policy Brief, February 2012, http://npc.umich.edu/publications/policy_briefs/brief28/policybrief28.pdf.

[4] See, Clare S. Richie, "Georgia's Decreasing TANF Funds: An Overview of the FY 2012 Allocation of TANF Funds in Georgia," June 2011, http://gbpi.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/20110622a.pdf.

[5] Liz Schott and Ife Finch, "TANF Benefits Are Low and Have Not Kept Pace with Inflation," Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 14, 2010, https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/10-14-10tanf.pdf.

[6] National Association of Child Care Resource and Referral Agencies, Parents and The High Cost of Child Care: 2010 Update, NACCRRA, 2010.

[7] Chad Stone, "Statement on the April Employment Report," Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 4, 2012, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/index.cfm?fa=view&id=3766.

More from the Authors