- Home

- North Dakota's Measure 2: High Risk For ...

North Dakota's Measure 2: High Risk For Little Reward

Michael Leachman, Phil Oliff, and Anderson Heiman

A proposal on the June 12 primary ballot would amend North Dakota's constitution to ban property taxes, a highly imprudent experiment that would fail to maximize the benefits of today's oil-driven economic boom to improve the state for future generations.

The list of dangers posed by Measure 2 is long. It would:

- Lock North Dakota into a course of action that is uncharted and risky. No state has ever placed a constitutional ban on property taxes or otherwise permanently eliminated them. Property taxes in North Dakota are a key source of funding for a wide range of essential local services. It is not possible to eliminate this funding without major disruptions to schools, cities, and counties across the state. Locking a ban on property taxes into the state constitution would make it especially difficult for the state to sustain funding for local services in the face of changing economic conditions.

- Make North Dakota's schools financially dependent on oil revenues, a risky move since oil taxes are a much more volatile revenue source than property taxes. Permanently shifting funding for schools from property taxes to oil revenues would leave the state's schools — and hence the education of its children and future workforce — vulnerable to a highly volatile industry whose revenue and in-state production can fluctuate greatly depending on world events, environmental lawsuits, and other factors beyond North Dakota's control.

- Leave funding for basic local services vulnerable to future reductions. In essence, the measure would require the state to provide localities with "block grants," set amounts of funding adjusted over time by a set formula. Other experiences with block grants indicate that they often erode in value over time, a result especially likely if the state faces unexpected needs in the future or enacts major cuts in other taxes. Some individual localities, such as those that are faster-growing, could be particularly ill-served by the block grant arrangement.

- Send large sums of North Dakota's money out of state, to the federal government and to property owners in other states. Under the measure, North Dakotans would pay more taxes to the federal government, since they would lose their ability to deduct property taxes from their federal income taxes. Measure 2 also would hand a windfall to out-of-state property owners at North Dakota's expense. That makes little sense. North Dakota is at a key moment in its history; to take full advantage of the quality-of-life gains oil has made possible, the state should maximize the share of North Dakota's money that stays in North Dakota.

- Waste a large share of oil revenues on an approach with very limited value to the state's future economy. The oil boom has created an historic opportunity to make investments that will improve greatly the lives of current and future North Dakotans. Measure 2 would lock into the state constitution a risky approach that would not assure that today's bounty is used to maximize the benefits for future generations of North Dakotans. Other, more sober uses of the oil revenue — investing in the state's children and in its public infrastructure, for example — would reap substantial gains for the state in the future. Tax cuts are an appropriate use of the oil boom revenues, but these cuts should not be locked into the state constitution and should be targeted to people living in North Dakota, especially those who can most use an income boost.

Measure 2 is being misrepresented as a strategy for inducing a dramatic, nearly immediate surge in the state's economy, above and beyond its current economic boom. These claims are overblown. In reality, Measure 2 would damage the state's economic potential by reducing its ability to invest heavily in its children and in the public infrastructure that helps form the foundation of future economic growth.

A Constitutional Ban on Property Taxes Would Be Unprecedented and Imprudent

Property taxes are the fundamental funding source for basic public services in local communities, towns, and counties across the country, and have been throughout the nation's history.[1] No state has ever enacted a constitutional ban on property taxes, or otherwise eliminated them. For North Dakota to do so would be unprecedented and reckless.

Every state has a property tax, often established at statehood. North Dakota has used property taxes to finance basic public services since statehood in 1889.[2] Property taxes generate over half the revenue North Dakota's local governments raise on their own to fund local public services, and 33 percent of all revenue sources for local government including fund transfers from the state and federal governments. [3]

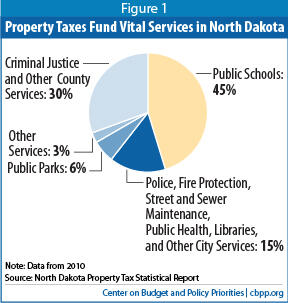

The property tax has significant strengths that make it a key component of North Dakota's overall system of state and local taxes. Property taxes tend to be a relatively stable source of revenue for local governments. They do not fluctuate as widely in response to swings in the economy as do sales or income taxes, the two other major sources of state and local revenue. Property taxes also directly benefit the businesses and individuals that pay them, since they fund local services. For example, the property tax pays the salaries of the police officers who patrol local streets and the teachers at the neighborhood school. Flaws in the property tax, such as the fact that it can have a disproportionately large effect on some elderly and low-income families, could be addressed through targeted changes to the tax; such potential changes are described later in this paper. Property taxes in North Dakota are a key source of funding for a wide range of essential local services. In 2010:

- 45 percent of North Dakota property tax revenues went to public schools.Image

- 30 percent went to counties. County tax dollars primarily pay for criminal justice services, including county sheriff's departments, prisons, and courts.

- 15 percent went to cities. City tax dollars largely fund local police and fire protection, but also pay for things like street and sewer maintenance, public health services such as immunizations, public libraries, and public transportation.

- 6 percent went to pay for public parks.

- The remaining 3 percent of property tax revenues went to fund a range of other services, including rural fire protection, and rural ambulance service.[4]

It is not possible to eliminate this funding without major disruptions to schools, cities, and counties across the state.

Placing a ban on property taxes in the state constitution would make it especially difficult for the state to sustain funding for local services in the face of changing economic conditions. Constitutions are hard to change, and the state could not easily restore property tax funding when other revenue sources decline.

Funding Schools with Volatile Oil Revenue Would Be Risky

Locking Measure 2 into the state constitution likely would result in the state's schools becoming significantly more dependent on oil taxes, a risky move since oil taxes are a much more volatile revenue source than property taxes.

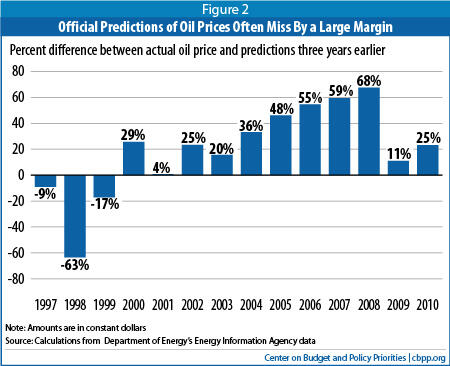

- Unpredictable events can cause oil prices to swing wildly. Oil prices are highly uncertain and depend on events that are impossible to predict, including production shifts and conflicts in the Middle East and the fluctuations of world economic cycles. "Energy market projections are subject to much uncertainty," the U.S. Department of Energy notes. "Many of the events that shape energy markets are random and cannot be anticipated. In addition, future developments in technologies, demographics, and resources cannot be foreseen with certainty." Since 1994, the Department's official projections of oil prices three years in the future have turned out to be wrong by an average of 33 percent; on two occasions, in 1998 and 2008, they were off by more than 60 percent.[7] Having schools rely on a revenue source as unpredictable as oil revenues would make planning very difficult and would leave the quality of children's education dependent on events well beyond North Dakota's borders.

- Changes in federal energy policy could reduce North Dakota oil revenues. Federal regulators could pursue policies that undermine the viability of the "fracking" technique typically used to extract oil and gas in North Dakota.[8] Future Presidents and Congresses also could enact major changes in federal energy policy, for example by sharply increasing federal taxes on oil and boosting subsidies for alternative energy providers, driving up the costs of oil relative to other forms of energy, which could slow oil production in North Dakota.

Measure 2 Would Leave Funding for Basic Local Services Vulnerable

By banning a major revenue source for towns, counties, cities, and other local governments and giving the state legislature authority over replacing the lost revenue (and how much of it to replace), Measure 2 would vastly increase the power of state legislators and the governor over the extent and quality of public services in towns, counties, and cities across the state. Measure 2 requires that local officials control how to spend the revenue the state legislature provides them, but gives the state legislature full authority over how much to provide.

The measure says that:

- The state must use oil revenues (and a few other more minor state revenue sources) to replace the share of K-12 education revenues not provided by the state prior to 2012. Measure 2 does not require the state to hold schools harmless for the entirety of their funding. Schools in North Dakota today are funded by a combination of local, state and federal dollars. If in the future state legislators were faced with a decline in revenue or an increase in the cost of meeting other pressing state needs, they would be required to replace the share of school revenues previously provided by local property taxes, but they would be completely free to reduce state funding for schools, leaving schools with less money overall.

- The state must use state revenue sources to "fully and properly" fund the legal obligations of cities, counties, and various other types of local government other than schools. The law does not specify what level of funding is "full and proper," leaving at the legislature's discretion each legislative session how much funding the state should provide to these local governments.

Since North Dakota has 53 counties, 357 cities, over 1,000 townships, and numerous city park districts, fire protection districts, and other local government entities, the legislature likely would resort to a formula for determining how to "fully and properly" fund each of these local government entities. In essence, the state legislature would provide localities with a "block grant," a set amount of funds adjusted by a set formula each year.

Other experiences with block grants indicate that they often erode in value over time, a result especially likely if the state faces unexpected needs in the future or enacts major cuts in other taxes.[9] Some individual localities would be particularly ill-served by the block grant arrangement. Fast-growing localities and others with pressing needs, for example, soon could find their block grant inadequate to their needs, leaving them to successfully lobby the legislature to provide additional funding, raise their own revenue, or go without enough funding.

Measure 2 Would Send North Dakota's Money Out of State

Measure 2 would send a substantial amount of North Dakota's money out of the state, rather than keeping it in-state to improve the state's quality of life or economy. This makes little sense. North Dakota is at a key moment in its history; to take full advantage of the quality-of-life gains oil has made possible, the state should maximize the share of North Dakota's money that stays in North Dakota.

- Under Measure 2, North Dakotans would pay more to the federal government than they otherwise would. Since taxpayers who itemize can deduct property taxes on their federal income tax returns, banning such taxes would increase the tax payments North Dakotans send to the federal government. Most of this money would go to support federal programs throughout the country, rather than funding local needs as the property tax does.

If Measure 2 had been in place last year, North Dakotans would have paid the federal government about $31 million more in federal income taxes for 2011. Taxpayers who itemize would see their federal income taxes increase by about 18 cents for every $1 in property tax reductions they receive under Measure 2.[10]

Granted, if Measure 2 fails, the legislature may enact tax cuts (without locking them into the state constitution) that also would increase the federal income taxes that North Dakotans pay. Sizeable personal income tax cuts enacted by the legislature last year had this effect, for instance. But Measure 2's failure would leave North Dakotans with more options to maximize the funds that stay in North Dakota. - Out-of-state businesses and property owners living in other states would get a windfall. A significant share of business property in North Dakota is owned by companies that are headquartered in other states. The North Dakota Association of Counties estimates that 37 percent of all commercial property taxes are paid by out-of-state firms. Currently, these firms are sending money into North Dakota to pay property taxes; under Measure 2, the money would remain in other states, where the firms would decide what to do with it.

These firms would be unlikely to invest their windfall in North Dakota. Businesses typically hire more workers and invest in new plants and equipment only when they anticipate increased demand for their products. If they don't anticipate increased demand, there is no reason to increase their workforce or invest in making more products.

For example, in 2011 Walmart paid about $7 million in property taxes to Richland County. If Measure 2 had been in place, Walmart would have saved this $7 million. There is no particular reason that the Arkansas-based company would have sent this money back to North Dakota in the form of increased hiring or other investments in the state, unless they were already planning to make those investments anyway. (The incentive effects, or lack thereof, are discussed further below.) More likely, most or all of the money would have simply added to the company's profits.

Similarly, a significant share of agricultural property taxes in North Dakota — about 16 percent, according to county association estimates — is paid by people or businesses in other states who own property in North Dakota. As with commercial property taxes, these out-of-state owners of farm property currently send their money to North Dakota; Measure 2 would let them keep it in their home state, where it will do no good for North Dakota's economy or quality of life.

By rejecting Measure 2, North Dakotans can choose how to use oil revenues and other revenues to strengthen the state's economy in ways that reserve the benefits for the state's residents to the maximum degree.

Measure 2 Would Waste an Historic Opportunity to Boost the State's Quality of Life

North Dakota's oil boom, and the resulting surge in public revenues, has created an historic opportunity to improve greatly the lives of future generations of North Dakotans. Measure 2 would squander that opportunity by wasting a large share of oil revenues on an approach with very limited value to the state's future economy.

As the last section detailed, banning property taxes would hand windfalls to the federal government and to property owners living in other states — at the expense of North Dakotans. Moreover, North Dakotans would spend some of their property tax savings on goods and services provided by businesses in other states — by buying products from companies online, for instance. This money also would leave the state economy. Other people would invest some of their property tax savings in the stock market, where it will do little good for North Dakota.

Even those companies and individual homeowners that are located in North Dakota may not use their property tax savings in ways that help the state economy. Companies typically make hiring and investment decisions based on their perception of current or future demand. If they don't see demand for their goods or services improving, they probably won't hire more people or invest in additional facilities or equipment, even if they have more money available to invest. These companies likely would add the property tax savings to their profits, some of which would flow to investors in other states. Wealthy individual property owners also are unlikely to change their spending patterns much; they already have enough money to meet their needs, and the added income won't compel them to buy more. Instead, they likely would save the extra money, putting it in the stock market or in their bank account, where it won't help grow the state economy.

Some proponents of Measure 2 have argued that it would boost the economy by attracting a flood of new businesses to the state, but that's very unlikely. Businesses make location decisions based primarily on fundamentals such as proximity to markets and suppliers and the availability of qualified workers. Measure 2 won't improve these fundamentals. Total state and local taxes, including property taxes, are just 2.3 percent of business expenses for the average corporation, much less than more fundamental costs such as labor, energy, and transportation.[11] Moreover, businesses typically have strong economic and social ties to their current locations, making relocation very costly and limiting the chances that a relatively small tax savings will lure a large number of businesses to move to North Dakota. Taxes matter to some extent, but not enough for Measure 2 to cause businesses to flock to the state.

Some Measure 2 proponents imagine a different scenario in which the measure produces so much economic growth it "pays for itself" by greatly increasing sales and income tax revenue.[13] There is simply no credible reason to think that property tax cuts ever "pay for themselves," and no

Beacon Hill Institute Exaggerates Measure 2’s Economic Impact

The Beacon Hill Institute, based at Suffolk University in Boston, has written two papers in support of banning property taxes in North Dakota. The papers’ findings are filled with illogical and inconsistent results that fail to support the case for Measure 2. For instance:

- One Beacon Hill paper finds that, under the scenario with the best jobs outcome, Measure 2 would cost North Dakota more jobs than it would create. Specifically, it finds that banning property taxes would force job cuts in the public sector that slightly exceed job gains in the private sector. The paper brushes over this result by nevertheless asserting that Measure 2 would greatly increase the disposable income of North Dakotans — an illogical result. The only way this would be possible is if the private sector jobs gained as a result of the measure paid massively more than the public sector jobs lost. More specifically, for Beacon Hill’s numbers to work, the average pay for new jobs gained would need to be about double the jobs lost. The Beacon Hill paper provides no explanation for how this could be the case.

- The other Beacon Hill paper, which also predicts a boom in disposable income as a result of Measure 2, appears to assume the state will take funds to pay for Measure 2 out of state reserves (instead of laying off thousands of state workers). This is a more realistic scenario, but ignores two important realities. First, because of other constitutional provisions, a large share of those reserves cannot be accessed by legislators to pay for Measure 2. Second, those reserves that are accessible by legislators almost certainly will be used to pay for other types of tax cuts or spending if Measure 2 fails, pushing the money out of state reserves into the economy. The Beacon Hill paper ignores this reality, instead choosing to calculate Measure 2’s impact relative to an unrealistic scenario in which the legislature holds surplus revenues entirely in reserve.

- Both papers conclude that if North Dakota banned property taxes, new business investment in the state would explode almost immediately, growing by a third or more in the first year after implementation. Such a huge, immediate boom in business investment from Measure 2 — over and above North Dakota’s already rapid economic growth — is highly unlikely, partly for reasons discussed in the text of this paper. For instance, businesses invest in new facilities and equipment when they see growing demand for their products, and they base location decisions primarily on fundamentals such as proximity to markets and suppliers. Measure 2 would not improve substantially any of these fundamental roadblocks to increasing business investment, especially in the first year after implementation, making a huge, immediate surge in business investment unlikely.

These problems, evident despite the papers’ lack of transparency, suggest that the Beacon Hill papers are exaggerating the economic impact of Measure 2. Their findings should not be considered credible assessments of the measure’s effect on North Dakota’s economy.

evidence has been offered in this case.[14] Even a questionable study by the Beacon Hill Institute often cited by Measure 2 proponents found that Measure 2 would come nowhere close to paying for itself. Instead, the study concluded that "[c]ombined state and local revenue would fall by $669 million in 2013 and $685 million in 2015."[15]

If there were a sound argument that it is easy to produce economic growth by banning property taxes, other states would have done so long ago (or at least one of them would have tried). The reality is that improving a state's economic trajectory is difficult, requiring long-term planning and a range of sober-minded strategies, including steady and ongoing investments in high-quality public institutions.

A Better Approach: Improving the Lives of Future Generations

The issue in North Dakota today is not how to produce economic growth; it's how to utilize the benefits of economic growth wisely so as to sustain it for the long term and for the benefit of all the state's residents. Measure 2 would lock into the state constitution a risky approach that would not assure that today's bounty is used to maximize the benefits for future generations.

There are more prudent and sober ways to ensure a bright future for North Dakota. One way is to invest heavily in improving the lives of children in North Dakota — in schools and health care, for example. Despite the state's growing wealth, about one in six children in North Dakota lives in poverty.[16] Since raising the income of poor children improves their success in school, and since children who grow up above the poverty line tend to earn more as adults, reducing child poverty would give a big boost to North Dakota's future economic potential.[17]

Investments in the state’s public infrastructure — its roads, bridges, flood control systems, parks, schools, job training facilities — also could yield significant returns for the state in the long term. Nearly every other state in the country would love to be in North Dakota’s position, with enormous opportunity to invest in its people and in the systems that will help its people thrive. For instance, North Dakota could invest in state-of-the-art job training systems that work closely with companies in growing industries to train the workers they need. Improving the state’s transportation systems, communications networks, flood management structures, agricultural research efforts, and other public systems also could pay off handsomely in the future.

Reducing taxes can still be part of a more balanced approach to using the revenues that have resulted from the oil boom. Without the constraints of Measure 2, these tax reductions could be crafted so that that they are targeted to people living in North Dakota, maximizing their in-state impact. And they could be targeted so as to address some of the existing inequities in the state tax system, such as the fact that people with lower incomes pay a greater share of income in taxes than people with higher incomes. Two advantages of targeting taxes to low-income families are that they are most likely to spend all of the new income they receive (increasing demand at local businesses), and their children in particular will benefit from their families' income gains far into the future.

One approach that would target families with low incomes is a property tax "circuit breaker." Circuit breakers, like the devices that keep electrical circuits from overloading, prevent property taxes from "overloading" a family's budget by "shutting off" property taxes once they exceed a certain share of the family's income.[18] North Dakota currently has a circuit breaker-like program that is limited to elderly or disabled homeowners and renters with low incomes. The program could easily be expanded to homeowners and renters of all ages, and lawmakers might also consider raising the income eligibility limit and the maximum property tax reduction to improve its reach.

Alternatively, lawmakers could reinstate the property tax credit program that was in effect in North Dakota from 2007 to 2009. The program provided a 10 percent credit against property taxes for homeowners up to a certain dollar amount. Again, this program could be improved to better target lower income households and to reach renters. Or, North Dakota could look to a homestead exemption that reduces across-the-board the amount of home value that is taxable for homeowners. Any of these options would provide a substantial reduction in property taxes for North Dakotans without endangering funding for state priorities like education and while leaving the flexibility to adapt to changing needs in future years.[19]

Measure 2 would lock North Dakota into a much more radical and risky approach, shifting school funding more heavily to volatile oil revenues, vastly expanding the power of state legislators over local affairs, and sending a large share of the revenues from North Dakota's oil boom to the federal government and out-of-state businesses and property owners.

End Notes

[1] In the United States, the use of property taxes dates back to the colonial era. http://www.lincolninst.edu/subcenters/property-valuation-and-taxation-library/dl/howe_reeb.pdf

[2] North Dakota's original constitution established a property tax in Article XI, Section 174.

[3] From Census State and Local Government Finance Data, available at http://www.census.gov/govs/estimate/.

[4] Note: Percentages do not add to 100 due to rounding. Source: State of North Dakota, Office of the State Tax Commissioner, 2010 Property Tax Statistical Report.

[5] Measure 2 reads, "The legislative assembly shall direct as much oil and gas production and extraction tax, tobacco tax, lottery revenue, and financial institutions tax as necessary to fund the share of elementary and secondary education not funded through state revenue sources before 2012." Oil production and extraction taxes account for the vast majority of the revenue collected from the revenue sources listed in this section of Measure 2.

[6] Annual Energy Outlook 2011, U.S. Energy Information Administration, DOE/EIA-0383(2011). http://www.eia.gov/forecasts/archive/aeo11/.

[7] Calculated by authors using data from U.S. Energy Information Administration, Annual Energy Outlook Retrospective Review: Evaluation of 2011 and Prior Reference Case Projections, DOE/EIA-0640(2011), http://www.eia.gov/forecasts/aeo/retrospective/.

[8] The EPA initiated a study in November 2011 to establish whether there is a relationship between hydraulic manufacturing and drinking water resources, http://www.epa.gov/hydraulicfracture/#outreach.

[9] See Kenneth Finegold, Laura Wherry, and Stephanie Schardin, Block Grants: Historical Overview and Lessons Learned, Urban Institute, No. A-63 in series "New Federalism: Issues and Options for States," http://www.urban.org/publications/310991.html.

[10] Analysis by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, April 2012.

[11] For a detailed discussion of this figure, see note 4 in Michael Mazerov and Mark Enriquez, "Vast Majority of Large Maryland Corporations Are Already Subject to "Combined Reporting" in Other States," Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, November 9, 2010. Available at https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/11-9-10sfp.pdf.

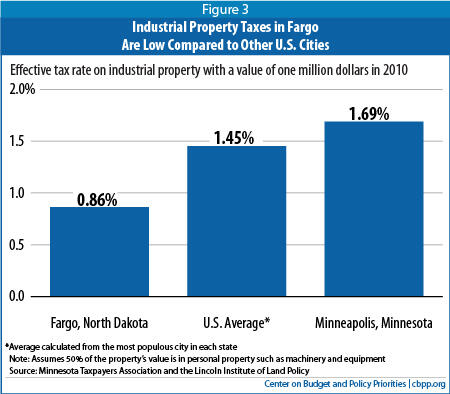

[12] Assumes half the value of the property is personal property such as machinery and equipment. Minnesota Taxpayers Association and Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, 50 State Property Tax Comparison Study, April 2011, http://www.lincolninst.edu/subcenters/significant-features-property-tax/upload/sources/ContentPages/documents/MTAdoc_NewCover.pdf

[13] Robert Hale, Brett Narloch, and Charlene Nelson, Property Tax Revolution: It's Our Property, Not Theirs!, Empower the Taxpayer, 2012, p. 7 (introduction), p. 31.

[14] There has been a debate in some states and at the federal level as to whether income tax cuts pay for themselves, but even on this point, there is strong consensus among economists across the spectrum that tax cuts lose revenue. See Evidence Shows That Tax Cuts Lose Revenue, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Revised July 21, 2008, https://www.cbpp.org/cms/?fa=view&id=507.

[15] David Tuerck, et. al., Eliminating Property Taxes in North Dakota, Beacon Hill Institute, April 2012.

[16] The U.S. Census Bureau estimates that 16.2 percent of North Dakotan children lived in poverty in 2010, the latest figures available.

[17] See Greg J. Duncan and Katherine Magnuson, "The Long Reach of Early Childhood Poverty," Pathways, Winter 2011, http://www.stanford.edu/group/scspi/_media/pdf/pathways/winter_2011/PathwaysWinter11_Duncan.pdf. See also Harry Holzer, et. al., The Economic Costs of Poverty in the United States, Center for American Progress, January 24, 2007, http://www.americanprogress.org/issues/2007/01/pdf/poverty_report.pdf.

[18] Karen Lyons, Sarah Farkas, And Nicholas Johnson, March 21, 2007, "The property tax circuit breaker: An introduction and survey of current programs," https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/3-21-07sfp.pdf.

[19] The cost and distributional impact of these three particular options will be detailed in a forthcoming report by the Institute for Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP).

More from the Authors