Unveiling his tax plan on February 22, Governor Romney's campaign said it would: 1) make permanent President Bush's tax cuts (but not those enacted under President Obama, which are scheduled to expire at the same time and which expanded several refundable tax credits for low- and middle-income families); 2) then cut individual income tax rates 20 percent below the Bush levels, reducing the Bush top rate of 35 percent to a new top rate of 28 percent; 3) repeal the estate tax; 4) repeal the Alternative Minimum Tax; 5) cut the top corporate tax rate by nearly 30 percent (from 35 to 25 percent); and 6) scale back unspecified "tax expenditures," mainly for high-income people. It would leave untouched the biggest tax break for high-income households — the 15 percent tax rate on capital gains and dividends — and eliminate capital gains taxes altogether for people with incomes below $200,000. Governor Romney's advisers also said the plan would preserve "revenue neutrality" and maintain the current degree of progressivity in the tax code.

As experts at the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center (TPC) have noted, it would be virtually impossible to achieve all of the plan's multiple goals at the same time. In particular, the Romney tax policy changes would almost certainly add substantially to the deficit. Assessing the plan, the TPC's Roberton Williams observed, "Nothing comes to mind to broaden the tax base enough to pay for the lower rates." [1]

Now, a new TPC analysis (issued March 1) backs up the skepticism with hard facts. It finds that, absent base broadeners, the Romney plan would cut taxes by $481 billion in 2015 alone, translating into a $4.9 trillion revenue loss over the coming decade. [2] Most tax experts believe that's far more than any conceivable set of base-broadeners (i.e., reductions in tax expenditures) could generate,[3] leaving the Romney plan as not "revenue neutral" but, instead, a significant revenue loser.

Moreover, a close reading of the document from the Romney campaign about the plan, as well as Governor Romney's February 23 op-ed in the Wall Street Journal and statements by Romney campaign advisor Glenn Hubbard, suggest that the plan is not, in fact, intended to be revenue neutral. Neither the campaign document nor the Romney op-ed actually says it is. Instead, both state: "Stronger economic growth and reductions in spending will help to ensure that these tax cuts do not expand deficits."[4] In other words, along with scaling back unspecified tax expenditures, the plan relies in substantial part on "dynamic scoring" — an assumption that tax cuts will boost economic growth and, in turn, federal tax revenues — and very deep budget cuts to avoid expanding the deficit.

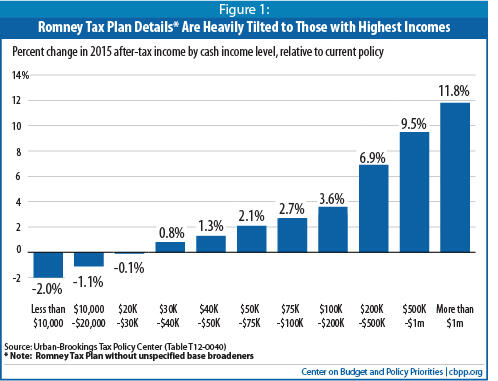

Finally, the Romney plan would significantly exacerbate the already serious problem of income inequality in America, conferring extraordinarily large tax cuts on the wealthiest Americans while raising taxes on people making less than $30,000 a year. TPC estimates that people who make over $1 million a year would get an average tax cut of $250,000 in 2015 (increasing their after-tax income by an average of almost 12 percent), while people making between $40,000 and $50,000 would get an average tax cut of $512 (increasing their after-tax income by an average of 1.3 percent), and people making between $10,000 and $20,000 would pay an average $174 more in taxes (decreasing their after-tax income by an average of 1.1 percent).

Revenues and Deficits

Although some news accounts cited Hubbard as calling the plan revenue-neutral, Hubbard is not defining "revenue" in the usual sense. As the Wall Street Journal reported, "Mr. Hubbard said three different revenue streams would keep the plan from increasing the budget deficit: the 'dynamic' effects of economic growth, the additional income that would be subject to taxation through base broadening, and spending cuts Mr. Romney plans that would reach $500 billion per year by 2016."[5]

The claim that the plan's large tax cuts would be financed in significant part by greater economic growth is one that proponents of tax cuts often make, but that Congress' official scorekeeper of tax proposals — the Joint Congressional Committee on Taxation (JCT) — and most other mainstream analysts do not accept. The claim is also inconsistent with the historical evidence. Proponents of both the 1981 Reagan and 2001 Bush tax cuts made the same claim, but deficits swelled after enactment of both of those tax cuts. Opponents of President Clinton's 1993 tax increases made the reverse side of this claim — that the tax increases would seriously injure the economy and, thus, depress revenues — but those tax cuts were followed by far more rapid revenue growth than in the 1980's and ultimately by budget surpluses. Of course, other factors played important roles in the swelling of deficits and the creation of surpluses, but the Reagan and Bush tax cuts clearly reduced revenue significantly while the Clinton tax increase clearly had the opposite effect.

TPC issued an analysis of the Romney plan on March 1, finding that it would cut taxes by $481 billion in 2015, or 2.7 percent of GDP. [6] (This doesn't count base-broadening measures, because the plan doesn't include any specific such measures.) Assuming the tax cuts would not take effect until January 1, 2014, this translates into a revenue loss of $4.9 trillion over the 2013-2022 period. This estimate assumes the revenue losses continue to equal 2.7 percent of GDP throughout the period, a standard assumption for estimating the effects of tax proposals over time.

These TPC figures measure revenue losses compared to a baseline that assumes all of the Bush tax cuts are extended. TPC's analysis also finds that compared to a "current-law baseline" — which assumes the Bush tax cuts, AMT relief, and normal "tax extenders" (such as the research and experimentation tax credit) expire on schedule — the new Romney proposals would lose about $900 billion in 2015. [7] That translates into a revenue loss of $9.1 trillion over the next ten years.

The TPC estimate indicates that the Romney tax cuts are one-third larger in size than the entirety of the Bush tax cuts, which produce annual revenue losses equal to approximately 2.0 percent of GDP.

Winners and Losers

The TPC analysis also finds that the Romney plan would confer extraordinarily large tax cuts on the wealthiest Americans, while actually raising taxes on people making less than $30,000. The TPC analysis shows that:[8]

- People making over $1 million a year would receive an average tax cut of $250,000 in 2015 — an increase of nearly 12 percent in their after-tax income — on top of the large tax cuts they would get from making the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts first enacted under President Bush permanent, which themselves would provide average tax reductions for these people of about $130,000 a year.[9]

- In contrast, people making between $40,000 and $150,000 would receive an average tax cut of $512, an increase of 1.3 percent in their after-tax income.

- People making between $10,000 and $20,000 would receive an average tax increase of $174, while those below $10,000 would face an average tax increase of $113. These tax increases (relative to the taxes that people would owe under a continuation of current tax policies) occur because the Romney plan shrinks three tax credits for low- and middle-income working families (the Earned Income Tax Credit, the refundable component of the Child Tax Credit, and the American Opportunity Tax Credit to help students afford college costs) by failing to extend the expansions in these credits that were enacted in 2009 and then extended through the end of 2012, along with the Bush tax cuts.

Table 1:

Average Tax Cut (or Increase) and Percent Change in After Tax Income in 2015

Under Romney Tax Proposal |

| Income | Average Tax Cut (Or Increase) | Percentage Change in After Tax Income |

| Less Than $10,000 | -$113 | -1.97% |

| $10-$20K | -$174 | -1.12% |

| $20-$30K | -$13 | -0.05% |

| $30-$40K | $262 | 0.79% |

| $40-$50K | $512 | 1.25% |

| $50-$75K | $1,122 | 2.06% |

| $75-$100K | $2,000 | 2.66% |

| $100-$200K | $4,051 | 3.56% |

| $200-$500K | $15,790 | 6.85% |

| $500K-$1M | $50,520 | 9.49% |

| More Than $1M | $250,535 | 11.83% |

Note: Romney Tax Plan without base broadeners.

Source: Urban Brookings Tax Policy Center, Table #T12-0040 |

The TPC analysis also finds that the benefits of the Romney tax cut would be heavily concentrated at the top of the income scale. Households making over $1 million a year constitute 0.4 percent of all households but would receive nearly one-third (31.4 percent) of the tax cuts (see Figure 1). Those making over $200,000 a year account for about 5 percent of all households but would get two-thirds (67 percent) of the tax cuts. Meanwhile, those making between $30,000 and $100,000 make up 41percent of all households but would receive 14 percent of the tax cuts.

These TPC figures reflect all of the components of the Romney tax plan except its unspecified base-broadeners, which TPC could not include because the plan lacks any specific base-broadening measures.

The Romney plan contains no specific information on what tax expenditures it would close or scale back to help offset the costs of its rate cuts and other major revenue-losing provisions. It is extremely unlikely, however, that policymakers could scale back tax expenditures enough to offset more than a fraction of these revenue losses.

In unveiling a plan last fall that — like the Romney plan — would reduce tax rates across the board and set the top income tax rate at 28 percent, leave the capital gains and dividends rate at 15 percent, and assume some scaling back of tax expenditures, Senator Pat Toomey called for a tax-expenditure limitation like one proposed by well-known economist and former Reagan advisor Martin Feldstein. [10] The Feldstein plan would limit a package of tax expenditures to 2 percent of a tax filer's adjusted gross income and apply that limit to all tax filers.

TPC found, in an analysis issued last summer, that if the Feldstein plan were applied only to taxpayers with incomes above $250,000, it would save just $48 billion in 2015.[11] Yet TPC's new analysis of the Romney Plan finds that $323 billion of its $481 billion reduction in tax liability in 2015 will be among people with incomes over $200,000.[12] Among high-income households, therefore, the Feldstein proposal would offset only a small fraction of the revenue loss from the tax cuts in the Romney plan. [13]

The Feldstein proposal would raise considerably more revenue than that (a total of $278 billion in 2011 according to Feldstein and his co-authors) because Feldstein would apply it to all taxpayers, not just those above $250,000. Feldstein and his co-authors have provided data showing that 71 percent of the revenue their proposal would raise would come from people with incomes below $200,000 and that the proposal would have a regressive effect. For example, the Feldstein proposal limits the tax exclusion for employer-sponsored health insurance (ESI) for all taxpayers. According to Feldstein, fully one quarter of his total $278 billion in savings comes just from this ESI provision as it applies to people under $75,000, and 45 percent of the $278 billion total comes just from this ESI provision for people under $200,000.

Governor Romney's recent statements suggesting he would make only limited changes in tax expenditures for middle-class families imply that his tax-expenditure proposals would raise significantly less than Feldstein's from people with incomes below $200,000. Yet even the full Feldstein proposal, with its substantial impacts on middle-income families — would fall about $2 trillion short of offsetting the revenue loss from the Romney tax cuts. And the Feldstein proposal would raise even less if the Romney reductions in tax rates are adopted. [14]

A TPC analysis issued in January[15] provides further evidence of how difficult it would be for Governor Romney to come close to paying for his tax cuts. TPC looked at the effect of curbing the largest tax expenditures — employer-sponsored health insurance, the mortgage interest deduction, the deduction for medical expenses, the deduction for state and local taxes, the deduction for charitable contributions, and the preference for capital gains and dividends. TPC estimated the impact of converting all of these tax preferences to flat 15 percent tax credits, thereby cutting the value of these tax preferences sharply for people in all tax brackets above the 15 percent bracket. TPC also looked at an alternative that would cut the value of all of these large tax expenditures by nearly 40 percent. TPC estimated that these two options — which likely go far beyond anything Congress would seriously consider — would raise $2.8 trillion and $2.4 trillion, respectively, over ten years. Moreover, if the capital gains and dividends tax preference was left intact — as Governor Romney proposes — the savings from these two options would be substantially less.

In other words, even if the political system could miraculously pull off such large reductions in popular tax expenditures, the revenue raised wouldn't come close to paying for the Governor's tax cuts. These aggressive and unrealistic measures would fall more than $2 trillion short.

Furthermore, the TPC estimates of the savings these options would produce reflect the savings under the current tax-rate structure. The proposals would raise less revenue if the Romney tax rate cuts were adopted.

Finally, if virtually all of the tax-expenditure savings that could be obtained were used to offset a portion of the costs of a big tax-cut package, then tax-expenditure reform could no longer help to achieve needed large-scale deficit reduction, as the attainable savings in that area would have been used up.

Governor Romney has strongly suggested that his plan would not provide large tax cuts to the very wealthy. How a tax plan with deep tax-rate cuts affects people at the top, however, depends in substantial part on its treatment of capital gains. The preferential tax rate on capital gains is, by far, the most lucrative tax expenditure for those at the top. Indeed, TPC estimates that more than 27 percent of the income of people who make more than $1 million comes in the form of capital gains and dividends.[16] It's extremely hard to cut tax rates sharply across the board without giving massive tax cuts to those at the top — and making the tax code less progressive — unless one also eliminates or greatly reduces the differential between the top income tax rate and the capital gains tax rate.

The Romney document notes that his tax plan would restore the top rate to the same 28 percent level as under the Reagan-era Tax Reform Act of 1986. It fails to say, however, that the 1986 law eliminated the capital gains differential, raising the capital gains tax rate to 28 percent. (Similarly, the Bowles-Simpson deficit-reduction commission called for lowering the top rate to 28 or 29 percent but also eliminating a lower rate for capital gains, along with other ambitious reductions in tax expenditures.)

Last year, JCT examined a plan similar in some key respects to Governor Romney's. The plan that it analyzed would cut tax rates about one-seventh below President Bush's tax rates, setting the top rate at 30 percent (compared with Governor Romney's 28 percent), while retaining the current preferential tax rates for capital gains (as the Romney plan would). The plan that JCT examined also reduced tax expenditures across the board (not just for high-income people) by enough to make it truly revenue-neutral (which the Romney plan does not do). JCT found that people making more than $200,000 would receive large tax cuts while those making less than $200,000 would, on average, face tax increases.

Governor Romney insists his plan would not raise taxes on middle-class families. If so, given the fiscal impact of cutting the top income tax rates (along with other tax rates) substantially, reducing corporate tax rates by nearly one-third, and abolishing the estate tax and the AMT, the plan would fall far short of raising the same amount of revenue as current policy. That is, the plan would raise much less than if policymakers permanently extended all of the tax cuts of the past decade, which itself would be inconsistent with the need to achieve large-scale deficit reduction.

Thus, the Romney plan would either lead to large increases in deficits and debt or require budget cuts of great depth — with a large share of the savings from those budget cuts used to offset the costs of the tax cuts, rather than for deficit reduction.

Finally, even if the tax changes themselves managed not to make the tax code less progressive — a goal that the Romney plan would be hard-pressed to achieve, given its proposals to cut tax rates across the board, abolish the estate tax and the AMT, and retain the current low rate for capital gains — spending cuts of the magnitude needed to offset the revenue losses would necessarily have to hit hard at Medicare, Medicaid, and/or Social Security and at programs for people with low or moderate incomes. It is hard to imagine that the net effect would not be to shift income up the income scale and widen after-tax income inequality.