Statement: Chad Stone, Chief Economist, on the January Employment Report

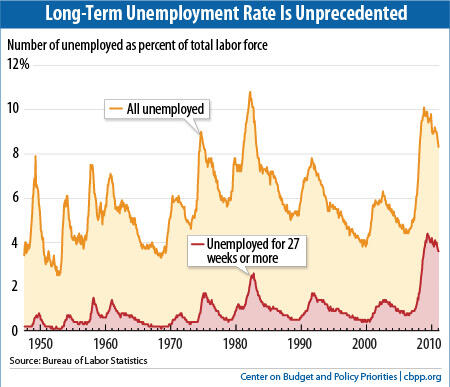

Today's jobs report is encouraging, but we should judge it against the overall sluggishness of the economic recovery and a persistently large jobs deficit that remains after 23 straight months of private-sector job creation. Payroll employment is still 5.6 million jobs short of where it was at the start of the Great Recession in December 2007, there are four jobless workers for every job opening, and long-term unemployment remains at an historic high level (see chart). Nothing in today's report should deter Congress from moving quickly to enact payroll tax cut/unemployment insurance (UI) legislation that would extend the provision of temporary federal emergency UI compensation through the end of the year — without cutting benefits or imposing new barriers to receiving benefits.

Forecasters do not expect a robust recovery anytime soon. The policymaking committee of the Federal Reserve said in its most recent statement that it "expects economic growth over coming quarters to be modest and consequently anticipates that the unemployment rate will decline only gradually." The Congressional Budget Office said in its latest The Budget and Economic Outlook that it "expects that, under current laws governing federal taxes and spending, economic activity will continue to grow slowly over the next two years."

Current economic conditions justify continuing federal emergency UI at the levels in place last year. Reducing the number of weeks of federal benefits, as proposed in the House-passed bill of December, would take purchasing power out of the economy and weaken the recovery. Other proposals in the House bill — denying benefits to workers with the requisite work history because they lack a high school degree or equivalent, forcing recipients to submit to drug testing, and allowing states to use UI funds for purposes other than paying benefits — are misguided. They should not be part of the extension of the payroll tax cut and UI now under consideration in Congress.

Federal emergency UI is a temporary program; as the economy improves, the maximum number of weeks of benefits will fall as states' unemployment rates fall. Once a sustained jobs recovery is underway, creating 200,000 to 300,000 or more jobs per month on a regular basis, and people are returning to the labor force confident they can find jobs, federal emergency benefits should expire. But the highest unemployment rate at which past emergency UI programs have expired is 7.2 percent — more than a percentage point below January's 8.3 percent.

About the January Jobs Report

Job growth was strong in January, but the job market has a long way to go to regain full strength.

- Private and government payrolls combined rose by 243,000 jobs in January. Private employers added 257,000 jobs. The decline of 14,000 government jobs reflected a loss of 6,000 federal jobs and 11,000 local government jobs, moderated by a gain of 3,000 state education jobs.

This is the 23rd straight month of private-sector job creation, with payrolls growing by 3.7 million jobs (a pace of 159,000 jobs a month) since February 2010; total nonfarm employment (private plus government jobs) has grown by 3.2 million jobs over the same period, or 138,000 a month. The loss of 498,000 government jobs over this period was dominated by a loss of 364,000 local government jobs. (The January jobs report includes the annual "benchmark" revisions, which raised the level of total nonfarm employment to 132.2 million jobs in December 2011, 266,000 above previously published estimates.) - In January, despite 23 months of private-sector job growth, there were still 5.6 million fewer jobs on nonfarm payrolls than when the recession began in December 2007 and 5.2 million fewer jobs on private payrolls. Growth of 200,000 to 300,000 nonfarm payroll jobs or more a month is typical in strong economic recoveries and will be necessary to close the jobs gap and restore full employment in any reasonable period of time. Payroll job growth has started to move into that range, but gains at least as large as we saw in January need to be sustained.

- The unemployment rate dropped to 8.3 percent in January, and the number of unemployed Americans was 12.8 million. The unemployment rate was 7.4 percent for whites (3.0 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession), 13.6 percent for African Americans (4.6 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession), and 10.5 percent for Hispanics or Latinos (4.2 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession).

- Unemployment rates and other household data for January are not readily comparable with past data because the January data reflect new "population controls" based on the 2010 Census, which increased the size of the population aged 16 and older and reduced the proportion of people with a job and the number of people working or looking for work as a share of the population. The population increase was concentrated in older workers and younger workers, which tend to have lower employment and labor force participation rates.

- The recession and lack of job opportunities drove many people out of the labor force, and we have yet to see a sustained return to labor force participation (people aged 16 and over working or actively looking for work) that would mark a strong jobs recovery. Although comparisons with past data can be misleading, the labor force participation rate was 63.7 percent in January, its lowest rate since 1983.

- The share of the population with a job, which plummeted in the recession from 62.7 percent in December 2007 to levels last seen in the mid-1980s, was 58.5 percent in January and has not been above that level since May 2010.

- Finding a job remains very difficult. The Labor Department's most comprehensive alternative unemployment rate measure — which includes people who want to work but are discouraged from looking and people working part time because they can't find full-time jobs — was 15.1 percent in January, down from its all-time high of 17.4 percent in October 2009 in data that go back to 1994, but still 6.3 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession. By that measure, almost 24 million people are unemployed or underemployed.

- Long-term unemployment remains a significant concern. Over two-fifths (42.9 percent) of the 12.8 million people who are unemployed — 5.5 million people — have been looking for work for 27 weeks or longer. These long-term unemployed represent 3.6 percent of the labor force. Before this recession, the previous highs for these statistics over the past six decades were 26.0 percent and 2.6 percent, respectively, in June 1983.

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities is a nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization and policy institute that conducts research and analysis on a range of government policies and programs. It is supported primarily by foundation grants.