- Home

- Testimony: LaDonna Pavetti, Ph.D., Vice ...

Testimony: LaDonna Pavetti, Ph.D., Vice President, Family Income Support Policy, Hearing on “Improving Work and Other Welfare Reform Goals”

Before the House Ways and Means Committee, Subcommittee on Human Resources

Thank you for the opportunity to testify today.

TANF was created 15 years ago with a balanced approach in mind – that our nation's cash assistance system would be redesigned to create an expectation of work for able-bodied recipients and that a safety net would be maintained for parents who were unable to work due to a short-term crisis, a work-limiting disability or because no jobs are available. When we consider the reauthorization of TANF, we need to consider both aspects of TANF, taking into account what we have learned during TANF's first 15 years.

In my testimony, I will focus on four key points related to these two aspects of TANF:

- TANF provides cash assistance for a very small share of poor families, and many who receive assistance face significant barriers to employment.

- State TANF programs are built on an expectation of work, but there is a mismatch between recipients' employment assistance needs and the narrowly-defined work activities that the statute recognizes.

- The TANF work participation rate is an inadequate measure of TANF's success or failure as a program that promotes and supports work and provides a safety net when work is not available.

- The safety net aspect of TANF is weak; TANF responded only modestly to increased need during the recent economic downturn, and then, only in some states.

First, however, I would like to highlight an immediate issue that merits policymakers' attention even before reauthorization. Congress should restore and renew full funding for 2012 for TANF Supplemental Grants, which were provided to 17 states every year since 1996, until now. Despite its name, this funding was meant to address serious inequities across states in the basic TANF funding formula, rather than as a "supplement." Recipient states have among the highest rates of overall poverty and child poverty, and on average, their TANF expenditures per poor child have been less than half those of non-recipient states. States are now scaling back programs that help unemployed TANF recipients find jobs, and TANF has responded only modestly to the recession, largely due to its fixed block-grant funding structure that provides states the same funds regardless of increases in need as a result of an economic downturn. The unprecedented loss of TANF Supplemental Grant funds for the 17 states this past June 30, will, among other things, make it harder for them to maintain or increase work engagement among recipients.

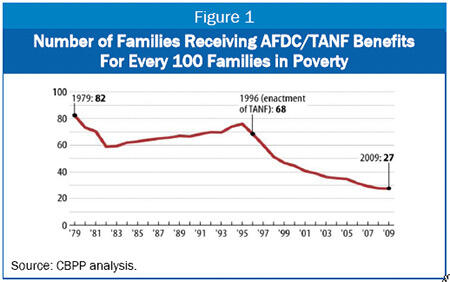

TANF Provides Assistance to a Very Small Share of Poor Families

Cash payments provided through the TANF block grant reach a much smaller pool of families than did payments provided through its precursor, the Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) program, and only a very small share of the poor families that are eligible receive them. In 2010, there were 1.9 million families receiving TANF cash assistance, down from 4.8 million in 1995, the year before TANF was created — a 60 percent decline even though unemployment is much higher now than it was in 1995. In about 40 percent of current TANF cases, only the children in the household receive cash assistance, leaving slightly more than 1 million cases in which a parent or adult relative also receives cash assistance. According to the Government Accountability Office, nearly 90 percent of this decline is due to fewer it the eligible families receiving TANF, not to a decline in the number of eligible families.[1]

This ratio declined in every state; in some states, the decline was especially pronounced. Looking at data for 2008 and 2009, in seven states, the TANF-to-poverty ratio was less than 10 – that is, fewer than ten families received cash assistance from TANF for every 100 in poverty. In 1994-95, when cash benefits were provided through the AFDC program, no state had an AFDC-to-poverty ratio that was lower than 32, and in half the states the ratio was at least 73. Today, only three states have a TANF-to-poverty ratio that is greater than 50.

Many Household Heads in TANF Families Face Significant Employment Barriers

Many of the parents remaining in the shrunken caseload who are expected to work face substantial barriers to employment, and this necessitates a different approach to helping them move from welfare-to-work than was envisioned when TANF was created. An Urban Institute study found that, based on data for 2005 and 2006, some 27 percent of TANF recipients faced significant work limitations — physical, mental, or emotional problems that prevent employment or limits the kind or amount of work that a person can do.[2] This is significantly higher than in the general population, where 5 percent of all adults and 6 percent of all low-income single mothers faced comparable work limitations. In addition, the study found that 14 percent of TANF recipients live with a family member who has a disability, which can further limit a TANF recipient's ability to secure, maintain, and progress in employment. It also found that employment rates among TANF recipients with disabilities are substantially lower than among recipients without disabilities.

State TANF Programs Built Around an Expectation of Work

A key goal of welfare reform was to reduce welfare dependency by helping welfare recipients move from welfare to work. States used the flexibility afforded them to transform their cash assistance programs into programs mandating and supporting work. Since the early years of welfare reform, states have promoted work by adopting policies that provide important support to families with one or more working parents and imposing penalties on parents that do not comply with work requirements. (Currently, nearly all states impose full family sanctions – that is, they do not provide any cash assistance to individual, including children, in families in which the household head does not comply with the work requirements.) All but one state established more generous earned income disregards that allows recipients who find employment to continue receiving partial cash benefits for a period of time, and states increased support for working families by providing more child care and transportation assistance.

What this means in practice is that families' experiences with the TANF cash assistance system are almost entirely defined by work requirements and whether or not they are met. In a typical state, parents are immediately required to participate in work-related activities. In many states, applicants must complete an initial set of work-related requirements before their application for assistance can be approved. The process often begins with an assessment that includes gathering information on an individual's education and employment history and identifying potential barriers to employment.

It is common practice for states to allow for some recipients with significant medical problems or mental health issues to be exempted from work requirements. In some states, these recipients are placed in specialized programs that are better equipped to meet their employment preparation needs. State exemption policies help to maintain the safety net aspect of TANF, as they are intended to provide recipients facing an immediate crisis, or facing significant medical or mental health issues, with basic assistance while they get those issues under control. Individuals who are exempt for participation usually are required to renew their exemption every three to six months. Permanent exemptions from work requirements are rarely granted, except for advanced age, usually for individuals over the age of 60 (of whom there are very few in the TANF program).

Individuals deemed able to work are referred to a contracted employment services provider or to a special employment services unit where they are provided assistance for finding a job. Programs vary in the way they structure their programs, but most involve some combination of providing individuals with job leads, requiring them to contact employers directly, and engaging them in structured classroom activities that teach skills needed to find employment (e.g., writing a resume). Typically, individuals' participation and progress are monitored daily. Individuals who do not meet the program requirements are sanctioned for non-compliance.

Individuals who find employment are encouraged to continue to receive cash assistance at a reduced level for extended periods. (This is a cost-effective way for a state to meet its work participation requirement.) Individuals who do not find employment may be placed in an unpaid work experience position or be required to perform community service. With a few exceptions, states have minimized the use of both community service and work experience because of the costs associated with finding placements, monitoring recipients' participation and providing child care. There also is no evidence that participation in these costly programs increases participants' employability.

Only a few states actively encourage TANF recipients to participate in education and training programs, and some others allow recipients to participate if they find such programs on their own. States that support TANF recipients who want to pursue education and training generally do so by developing relationships with existing providers such as community colleges. Often, TANF agencies must identify additional activities in which such recipients can participate, because many training and/or educational programs do not provide sufficient hours for TANF recipients to meet their work requirements.

Narrowly-defined TANF Work Activities Not Aligned with Recipients' Needs

The available evidence indicates that low-income unemployed parents fare best – that is, they experience the most significant increases in employment and earnings — when states employ a "mixed" approach.[3] When such an approach is used, recipients are encouraged to pursue the path to employment that will lead them to the best outcomes. For some, this means waiting for a more stable job to come along instead of taking the very first job they find. For others, it means participating in an education or training program that will help them gain the knowledge and skills to qualify for jobs that pay more adequate wages. And for those with limited work experience, it may well mean taking the first job they can get so they can establish a foothold in the labor market. Recipients with significant barriers to employment may need to stabilize their lives by seeking mental health, substance abuse or medical treatment before they can sustain full-time employment.

Although families come to TANF with different needs and problems, few states have implemented a mixed approach or develop individualized plans based on an individual family's needs and circumstances. Instead, most states treat all recipients the same. They do so in hopes of maximizing participation in the narrowly-defined set of work activities that will allow recipients to be counted as meeting the work participation rate standard.

The work participation rate only counts participation in 12 specified categories[4] of activities, and then only when participation is for a substantial number of hours, generally 30 hours per week (20 hours for single parents of young children). There are limits on how long participation in some of these activities can count, such as only six weeks per year for job search or job readiness (extended to 12 weeks when a state's economy is weak). In addition, hours of participation in some of these 12 activities do not count toward the work rate unless they are on top of 20 hours a week of participation in those that are considered "core" activities. A state gets no credit toward the work rate for any hours of participation that are less than the required number of hours, or for participation in activities that may fall outside of the restrictions on counting certain activities. As a result, many states do not report, and in some cases, their systems may not track, significant work activity participation taking place below these thresholds.

Furthermore, many of the activities that today's TANF recipients often need to be prepared for work do not count toward the work rate. For example, participation in substance abuse treatment that a recipient needs to be able to land and hold a job can only count as a part of job search/job readiness, and states generally can only count participation in job search/job readiness for six weeks in a year. Thus, after a person completes several months of substance abuse treatment and would then benefit from structured job search, the state is barred from receiving credit for the individual's participation in job search activities. And, if the individual already used her countable job search period as the first activity — an approach that many states take in their programs — the state would get no credit for her subsequent participation in substance abuse treatment.

By way of another example, a state operating a successful subsidized employment program, and committing substantial resources in helping families receive paychecks rather than cash assistance and get real work experience, cannot count these families as part of the work participation rate unless the state continues to provide them with a TANF cash grant on top of their pay checks. Such a barrier is counter-productive, especially since subsidized employment programs have been a tremendous recent success under TANF, with programs in 39 states and the District of Columbia placing over 260,000 persons in jobs in 2009 and 2010 through the now-expired TANF Emergency Fund. One thing that we learned here is that people are eager to work and will respond strongly to such an opportunity. In Illinois, for example, response was so overwhelming that the state had to close its subsidized employment program to new entrants after the first few months, and all told, it made over 35,000 paid job placements. But, because most of these families were not receiving cash assistance, they did not count toward the state's work participation rate.

TANF Work Participation Rate Is an Inadequate Measure of the Success or Failure of TANF as a Work Program

The need to meet TANF Work Participation Rate has played a large role in shaping state program design and has been a central focus of state actions. Yet the rate does not measure the full scope of welfare-to-work activities — and it does not measure whether states are successful at achieving the primary work-related goal of TANF — to improve recipients' employment outcomes. In virtually every state, TANF is temporary, and efforts focus on work. But the work participation rate does not capture this strong work focus of state TANF programs across the country. Here is evidence that this is the case. Data from the 2008 panel of the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) indicate that among all parents who were new TANF recipients, 56 percent worked at some point during the first year they received TANF; among able-bodied recipients the share that worked was even higher, at 68 percent. In contrast, the TANF Work Participation Rate achieved in FY 2009 for the United States as a whole was just 29.4 percent. If one of the key goals in TANF is to help TANF recipients become active participants in the paid labor market, then what we should care about is the share of families who are employed within some specified period of time and whether states systems are in place to promote and encourage work, not whether those who are receiving assistance are engaged in a narrow set of work activities that may or may not increase their employment prospects.

Focus on meeting the work participation rate has led many states to discourage participation in activities that do not count towards the work rate, even if such activities are effective in helping recipients gain or retain employment. (To be sure, some states have wisely continued to provide activities that are tailored to meet the work preparation needs of families on their caseload even if such participation does not count toward meeting the work rate.) Moreover, the burden of verifying and documenting hours of participation consumes very large amounts of staff and work contractor time and resources that could be better spent helping recipients prepare for work than on paperwork. Of course, states should be held accountable — but to a measure indicating progress toward employment goals rather than to the details of processes; this is federal overregulation at its worst. The data-heavy capturing of participation processes fails to tell us much about outcomes such as ongoing employment, sustained exits from poverty or progress on employability.

The work rates are effectively a mismatch for the work-related needs of the caseload. In fact, the rates actually operate as a disincentive for states to incorporate evidence-based practices into their welfare employment programs and to design programs that address the often-complex employment barriers of the families receiving assistance. The current work rate rules penalize states that accommodate individuals with disabilities, for example, through work plans setting fewer hours of participation because of a disability, even though such accommodations may be required by the Americans with Disabilities Act. To avoid these disincentives, some states have stopped serving the most disadvantaged families in their TANF programs and now serve them in programs funded solely with state dollars that are not used to meet the state's maintenance-of-effort requirement.

States often gear engagement with participants toward meeting the work rates first and foremost, and may try only secondarily to meet the actual work-related needs of families they are serving. In short, the work rates (and states' pre-occupation with meeting them) interfere with states providing the types of help to prepare for work that many of the families on TANF need most if they are to become productive members of the workforce. In this way, the current work rate rules frustrate the fundamental purpose of TANF.

Families Not Counted as Meeting the Work Rate for Understandable Reasons

When we look at which recipients are not counting toward the work rate, we see understandable reasons for much of that and even clearer reasons why the work participation rate is an inadequate measure of success or failure. Reasons why recipients are not counted as meeting the work rate include: partial participation but not enough hours, for justifiable reasons; the presence of parents whom state policies or legislatures have sensibly determined should not be required to work or whom Congress has decided should be excluded from work participation measurement; and recipients who are in the process of being sanctioned.

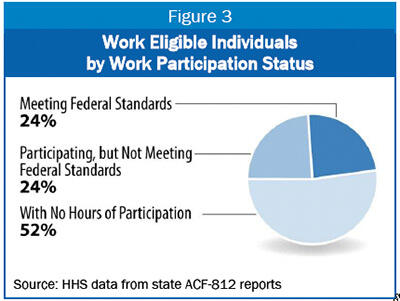

The specific mechanics for calculating the work rate lead to rates that misleadingly suggest that about half of the work-eligible population is not engaged in employment-related activities.[5] However, an examination of the data that states have reported to HHS on the reasons why individuals are not counted as meeting the work rates shows that the share of recipients genuinely expected to be engaged in work but counted as not meeting the rate is actually small.

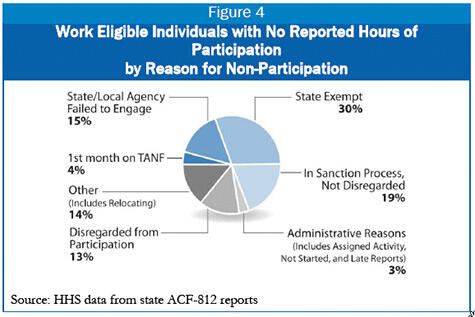

It also is worth looking at families with no hours of participation in March 2011. About half (52 percent) of those who are "work-eligible" individuals are listed as not having any hours of work participation, a figure that seems disturbing at first blush, but understandable upon closer examination. (See Figure 4.) Looking more closely at the breakdown of those with no hours of participation, people fall into the following categories:

- Disregarded under federal law: People who are disregarded from the participation rate calculation under the federal statute make up 13 percent of those listed with no hours of participation. Individuals are disregarded from the calculation mostly for three reasons: (1) single parents of a child under age 12 months (once in a lifetime), (2) persons in sanction status (who are disregarded only for the first three months), and (3) persons participating in tribal work programs. (Persons who are disregarded from the work rate under federal law are technically considered "work-eligible" individuals, so HHS includes them in the universe of those with zero hours even though they ultimately are not included in the final work rate calculation; this can make for confusion in understanding what the numbers represent.)

- People who are in the process of being sanctioned: About 20 percent of those shown as having no hours of participation are those who are in the process of being sanctioned but are not disregarded from the work-rate population under federal law. Federal law disregards persons in sanction for three months. But this disregard does not cover those just getting notice of an impending sanction or those who have been sanctioned for more than three months. The sanction system is working with regard to those people, but the 52 percent figure may incorrectly imply that it is not doing so.Image

- People exempt under state laws or policies: Some 30 percent of those with no hours are exempt under state law or policies, with 40 percent of these being people who are exempt due to a finding of illness or disability. Other state exemption reasons include individuals over age 60, illness or disability of a child or other family member, or other good cause. These exemptions are generally are granted for a limited duration, such as three to six months, and then are re-evaluated.

- People in their first month on TANF: Four percent of those without any reported hours of participation are those who are in their first month on TANF and have not yet been placed in a work activity.

- Failure to engage in work activities: Only about one in seven of those with no hours of participation (15 percent) are individuals whom the state or local agency has failed to engage in work or additional activities.

- Other reasons: The remaining 13.6 percent had other reasons for non-participation. Examples given by HHS include cases that are being closed mid-month, cases where an employment assessment is pending, cases where a family is about to reach the time limit, and cases where a scheduled work activity or appointment has recently been missed and appropriate action is pending.

TANF's Modest Response to the Economic Downturn Has Exposed TANF's Weaknesses as a Safety Net

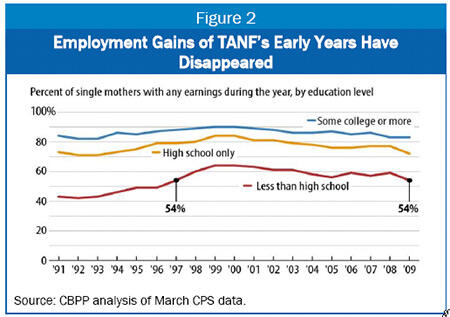

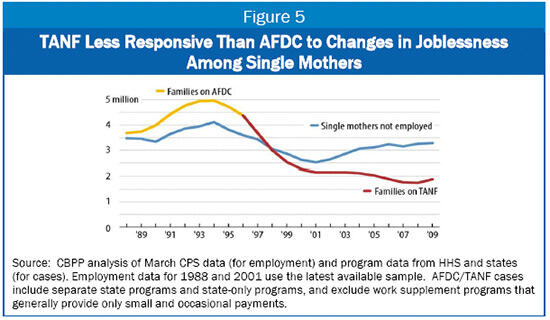

A robust work-based safety net requires not only that individuals receive assistance to find employment when the economy is strong, but also that a safety net be available when the economy falters. In most years, the caseload in the old AFDC program rose and fell to reflect changes in the number of jobless single mothers. Beginning in 2002, however, the two trends diverged: the number of jobless single mothers started rising, while the number of families receiving TANF kept falling. While TANF caseloads have increased modestly more recently, the gap between the number of jobless single mothers and the number of families receiving assistance remains very wide. (See Figure 5.)

The recent recession has exposed serious weaknesses in TANF's ability to respond to significant changes in the economy, resulting largely from its block-grant structure. Under TANF, federal funding does not rise when caseloads increase in hard economic times — unlike AFDC, under which the federal government shared the costs of increased caseloads with the states. With AFDC, federal funding rose automatically during economic downturns as state caseloads expanded, enabling states to respond to rising hardship and poverty.

Under the TANF structure, many states' TANF programs have responded inadequately — or not at all — to the large rise in unemployment during this very deep recession, leaving large numbers of families in severe hardship. In 16 states, TANF caseloads rose by less than 10 percent between December 2007 and December 2009; in six states, caseloads actually fell. This performance contrasts sharply with that of SNAP (formerly known as the food stamp program), where funding expands automatically during economic downturns to respond to rising need. The number of SNAP participants rose by 45 percent during the same period, as the number of unemployed people doubled and they and other households lost income.

Moreover, states whose TANF programs were more responsive to the greater need for assistance are now cutting their TANF cash assistance programs to shrink the amount of TANF expenditures used to support unemployed parents, despite a continuing poor job market. At least four states have cut their already-low monthly cash assistance benefits, which will push hundreds of thousands of families and children below — or further below — half of the poverty line. Several states have also shortened lifetime time limits on TANF benefits (which already were 60 months or less) and others have cut TANF-funded support for low-income working families.

Many of these cuts — including cuts in services and supports to help poor parents find jobs — run counter to states' longstanding approaches to welfare reform. Moreover, the specter of cuts in benefits just when they are needed most — during a serious economic downturn — was discussed at length when the TANF law was designed in 1995 and 1996 and was an outcome that the law's designers sought to avoid. It is now clear that further work is needed to prevent this outcome in future recessions.

Looking Toward Improving State TANF Programs

How can Congress help and encourage states to improve the effectiveness of work programs for families on the caseload while maintaining an adequate safety net for families who, through no fault of their own, are unable to find employment or are unable to work? Many TANF experts and state administrators believe that the work participation rate is a seriously flawed measure of performance that encourages TANF agencies to place recipients in activities that will count toward meeting the rate rather than activities that best improve the family's prospects of gaining and holding employment. The work participation rate also discourages states from serving some of the most disadvantaged families at all. The GAO has described the TANF work participation measure as of "limited usefulness" in evaluating TANF. There are a range of options from which Congress can choose to bring the focus to work, and not just work rates.

- Redefine how TANF measures state performance. The easiest way for states to meet the Work Participation Rate is to serve fewer families over time and to avoid serving families with significant employment barriers, even though they are the very families that have the most to gain from employment assistance. Congress should give states the option to develop alternative measures of success that more adequately reflect TANF's goals, such as participants' employment rates and earnings. In addition, states that serve a greater share of eligible families in need should be rewarded, not penalized, for providing a safety net to families who have nowhere else to turn for basic support for themselves and their children.

- Redefine TANF's work requirements to better reflect the diversity of the TANF caseload. Under current rules, only a narrowly defined set of activities count toward the Work Participation Rate, and these are not a good match for the needs of much of the current caseload. Simplifying the work requirements and expanding the types and duration of activities that can count toward the work rate would encourage states to serve more needy individuals, especially those whose employment prospects are the most limited without help.

- Require greater investments in work activities. States that do not meet applicable performance measures should be required to invest additional funds in work-related activities. The current penalty structure would withdraw federal funds from state TANF programs, further impairing state resources to meet families' employment-related needs. A state that fails to meet performance measures should be required to spend an increased share of its TANF spending (including both state and federal funds) on work-related activities rather than pay a fiscal penalty.

- Redesign and adequately fund the TANF Contingency Fund. Congress created the Contingency fund as an essential adjunct to the TANF block grant to provide states with needed resources during economic downturns when fewer jobs are available, since the block grant itself does not respond to changes in need. But the Contingency Fund is not well targeted and has provided only limited help to states during the current downturn. Congress can significantly improve the fund by: (1) making it more practicable for states with high unemployment to qualify for resources from the fund; (2) requiring states to use the fund for activities that respond directly to a weak economy — such as subsidized employment — rather than to simply help cover their ongoing costs; and (3) providing adequate contingency funding.

The work participation rate should be improved to measure employment outcomes for TANF participants, and work requirements should be simplified to allow states to guide recipients to the employment path that will lead them to the best employment outcomes. But, without other major improvements that extend beyond the program's work requirements and how they are measured, TANF will continue to fail the large majority of poor parents who today are neglected by TANF altogether as a result of the program's greatly shrunken reach in the face of increased need.

Congress should not only strengthen TANF but do so promptly. The last time TANF came up for renewal, in 2001, it took Congress more than four years to pass comprehensive reauthorization legislation — a delay that set back state program innovations. We should not allow the same thing to happen again.

End Notes

[1] "Temporary Assistance for Needy Families: Fewer Eligible Families Have received Cash Assistance Since the 1990s, and the Recession's Impact on Caseloads Varies by State," Washington, D.C.: United States Government Accountability Office, GAO-10-164, February 2010, http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d10164.pdf.

[2] Pamela Loprest and Elaine Maag, "Disabilities among TANF Recipients: Evidence from the NHIS," The Urban Institute, May 2009. http://www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/411883_disabilitiesamongtanf.pdf

[3] Gayle Hamilton, "Moving people from Welfare to Work: Lessons from the National Evaluation of Welfare-to-Work Strategies," New York: MDRC, July 2002, http://www.mdrc.org/publications/52/full.pdf.

[4] The 12 categories of work activities are: unsubsidized employment, subsidized private sector employment, subsidized public sector employment, work experience, on-the-job training, job search and job readiness assistance, community service programs, vocational educational training (up to 12 months for an individual), job skills training directly related to employment, education directly related to employment (for those with no high school completion or GED), secondary school or GED, and providing child care to participants in community service programs. Participation in some of these activities can only count on top of 20 hours of participation in "core" activities. Some participation can only count for limited periods or if other limitations are met.

[5] The TANF work participation rate that a state achieves is a formula. The numerator is the number of individuals who are participating in countable activities for the required minimum number of hours (while considering the restrictions on when activities can count). The denominator is the number of persons who are considered work-eligible (as defined by HHS) adjusted downward for certain groups that the federal law disregards from the work rate — single parents of a child under age 12 months (once in a lifetime), persons in sanction status (who are disregarded only for the first three months), and persons participating in tribal work programs. The denominator includes many individuals who states have determined should not be required to work or are in the process of being sanctioned but are not disregarded because the sanction has not yet been imposed or has continued for more than three months.

[6] "Engagement in Additional Work Activities and Expenditures for Other Benefits and Services, March 2011: A TANF Report to Congress," U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, July 2011.

More from the Authors