- Home

- New Estate Tax Rules Should Expire After...

New Estate Tax Rules Should Expire After 2012

Shrinking the Tax Beyond the 2009 Level Is Unaffordable and Unnecessary

The tax-cut compromise enacted in December established estate tax rules for 2011 and 2012 that are considerably weaker than those in effect in 2009, the last year before the tax temporarily expired in 2010. The new rules will cost about $23 billion more than reinstating the 2009 rules over the same two years, yet will benefit only the largest one-quarter of 1 percent of estates, since they are the only ones that that would owe any estate tax under the 2009 rules.

Taxable estates will receive more than $1 million apiece in tax breaks this year from the new rules, on average, and estates worth more than $20 million will receive an average of nearly $3.8 million apiece. In light of the nation’s serious long-term budget problems — and proposals to slash a wide range of government services, particularly Medicare, Medicaid, and programs for low-income Americans — it would be irresponsible to extend these new rules beyond 2012.

Tax Had Already Weakened Considerably Under 2001 Law

The 2001 tax legislation phased down the estate tax considerably. By 2009, the value of estates exempt from taxation had risen to $3.5 million for individuals (effectively $7 million for couples), up from $1 million for individuals ($2 million for couples) scheduled under prior law, and the marginal tax rate on the value of an estate above these thresholds fell from 55 percent to 45 percent. As a result, a tax that affected only the country’s largest 2 percent of estates in 2001 touched only the largest one-quarter of 1 percent of estates by 2009.

Due to the peculiarities of the 2001 law, the estate tax expired in 2010 but was scheduled to return in 2011 under the rules set by pre-2001 law, with an individual exemption of $1 million and a top rate of 55 percent. That was forestalled by the tax-cut compromise enacted in December (P.L. 111-312), which raised the exemption level to $5 million for individuals ($10 million for married couples) and lowered the marginal rate to 35 percent for 2011 and 2012.

Come 2013, the estate tax is once again scheduled to return to pre-2001 levels. While that outcome is unlikely, the scheduled reversion will provide an opportunity to revisit estate tax policy in the context of the hard fiscal choices the nation faces.

2009 Rules Were More Than Generous

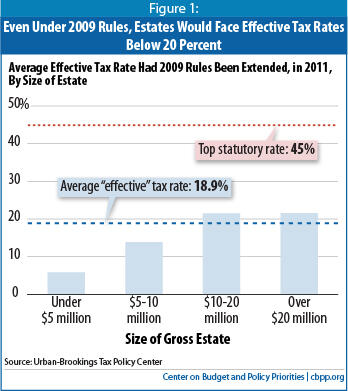

Even under the 2009 rules, very few estates paid the estate tax. According to recent estimates from the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center (TPC), only 6,460 estates nationwide — one-quarter of 1 percent of estates — would have owed any estate tax in 2011 had the 2009 levels been extended; fully 99.75 percent of estates would have been passed on tax free. Thus, 99.75 percent of estates will not benefit from the more generous exemption level and lower rate instated under the tax-cut compromise.

The above two points — that few estates owed any tax under the 2009 rules and that taxable estates paid relatively low rates — are especially true with regard to small businesses and farms, two groups that estate-tax critics have often cited as overly burdened by the tax. Only 110 small farm and business estates in the entire country would have owed any estate tax in 2011 if the 2009 rules had been reinstated, TPC estimates. [3] Under the new rules, only 50 small farms or businesses will owe estate tax this year.

Moreover, due to a number of special provisions targeted to farm and business estates, taxable small business and farm estates will face lower effective tax rates than other estates, whether under 2009 rules or the new compromise rules. If the 2009 rules had been reinstated, those few small business and farm estates that were taxable at all would have faced an average effective tax rate of 11.5 percent this year, according to TPC — well below the capital gains rate. Under the new compromise rules, their average effective rate will be even lower: 7.4 percent.

Without Estate Tax, Substantial Amount of Income Would Go Untaxed

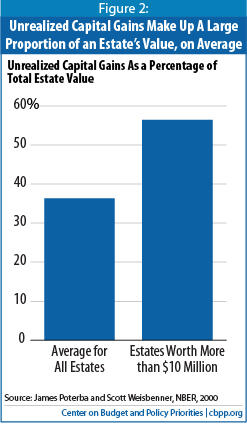

A common misconception about the estate tax is that all of the assets it affects have already been taxed. In fact, a substantial proportion of most estates consists of unrealized capital gains — i.e., investment income that has never been taxed. This is particularly true for larger estates. Another common misconception is that heirs pay income tax on the value of the estates they receive, which they do not.

Estate Tax Serves as Backstop to Capital Gains Tax

Generally, when an investor sells an asset for more than what it was worth when the investor acquired it (i.e., the asset’s purchase price, in most instances), the increase in the asset’s value is counted as income and taxed as a capital gain. If the investor has held the investment for long enough (generally 18 months), the gain is taxed at a substantially reduced rate, currently 15 percent for taxpayers who are above the 15 percent income tax bracket.

Moreover, suppose Mr. Jones’ daughter inherits the stock, and that by 2012 it is worth $1,200. If she decides to sell the stock in 2012, she will owe capital gains taxes on only the $200 capital gain between 2009 and 2012 — not on the full $1,100 growth in the stock’s value since her father’s original purchase.

Unrealized capital gains account for a significant proportion of the assets held by estates — a little more than one-third, according to a study by economists James Poterba and Scott Weisbenner.[5] For the largest estates, the proportion is higher: 56 percent of the value of estates worth more than $10 million comes from unrealized capital gains. (See Figure 2.)

Thus, the estate tax plays an important role as a backstop to the capital gains tax. If there were no estate tax, unrealized capital gains would never be taxed. Among other things, that would create an incentive for people to avoid taxes by retaining capital gains until death, discouraging them from allocating their capital in the most economically efficient ways.

This backstop function is especially important because the estates large enough to owe estate tax hold a disproportionate share of all unrealized capital gains. In 2006, the wealthiest 0.3 percent of households received 61 percent of capital gains income, according to TPC. [6]

Heirs Do Not Pay Income Taxes on Bequests They Receive

Another common misperception is that heirs pay income taxes on the portion of the estate that they inherit. In reality, bequests are not subject to the income tax; the entire estate is subject to the estate tax, after which each heir receives his or her share of the estate without paying further taxes on it.

This is a very good deal for the vast majority of estates, which are passed on tax-free. It’s still a good deal for most estates subject to the estate tax, because the effective tax rate on the estate is lower than what most heirs would pay if their inheritances were taxed as income.

New Rules Provide Large and Unnecessary Windfalls — Especially to Biggest Estates

Only the wealthiest 1 in 400 estates will benefit from the lower rate and more generous exemption level instated under the tax-cut compromise, because they are the only estates that would have owed any tax under the 2009 rules. [7] Based on prior estimates from the Joint Committee on Taxation, we estimate that the provision will cost about $23 billion more than it would have cost to reinstate the tax at its 2009 level for two years; all of that $23 billion will go to the wealthiest 0.25 percent of estates.

On average, the estates that benefit this year from the provision will see a benefit of more than $1 million apiece. [8] The largest estates — those worth more than $20 million — will benefit the most, receiving nearly $3.8 million apiece.

Large Estates Also Benefit from Gift Tax Reunification

The tax-cut compromise also includes a change in the gift tax that will benefit large estates in particular. The gift tax, whose rate is equal to the estate tax rate, is levied on all gifts from one individual to another that total more than a certain amount (known as the annual gift exclusion) in any given calendar year. The gift exclusion is $13,000 in 2011.

For assets whose value grows over time, transferring them as gifts during the giver’s lifetime rather than waiting to transfer them through the estate upon the giver’s death allows the owner to transfer them while they have a lower value. This can produce considerable tax savings, especially when the asset is gifted a decade or more before the giver’s death.

Individuals may exempt from the gift tax a certain lifetime value in gifts that exceed the annual gift exclusion. Prior to 2001, there was a single lifetime exemption amount for the estate and gift taxes — in other words, individuals had a single amount that they could divide between gifts (in excess of the annual gift exclusion) given tax-free during their lifetime and assets transferred tax-free through their estate after their death. Any exemption amount not used for the gift tax could be used for the estate tax.

When Congress sharply limited the estate tax as part of the 2001 tax legislation, it decoupled the gift tax exemption (which remained at $1 million) from the estate tax exemption (which increased gradually, to $3.5 million by 2009). This allowed individuals $1 million in lifetime gifts that were exempt from the gift tax, which counted toward the $3.5 million that could be bequeathed tax-free through an estate. The December 2010 tax legislation reunified the estate and a wealthy gift tax exemptions for 2011 and 2012 — at a $5 million level. This means that between gifts that an individual gives during his or her life and the estate that he or she leaves at death, the individual can now transfer $5 million tax free.

This sharp sudden increase in the gift tax exception is of particular value to the wealthiest individuals. Those whose estates are only modestly larger than $5 million presumably will be less likely to take full advantage of this change, because doing so might make it more difficult for them to retain assets they wish to keep through the end of their lives. But people who expect to have estates worth $15 or $20 million or more can maximize their benefit from this change, by gifting assets (while they are still alive) that are likely to appreciate in value quickly. By doing so, they will use up less of their $5 million exemption than if they let rapidly appreciating assets continue to grow for a number of years and then transfer those assets as part of their estate.

Consider, for example, two retired investment bankers with asset portfolios that consist half of bonds and other stable investments and half of stocks and other riskier investments. Assume one of the portfolios is worth $5 million and the other $10 million. The banker with the smaller portfolio could, in theory, apply the gift tax exemption to his entire portfolio, but that likely would not be advantageous for him. By contrast, the banker with the larger portfolio could apply the gift tax exemption to up to $5 million in stocks. If the bond portion of the portfolios grows at 2 percent per year while the stock portion grows at 8 percent, the banker with the larger portfolio will end up benefitting far more from the timing shift because he would be able to transfer, through the gift tax, a substantial amount of rapidly appreciating assets that he otherwise would have transferred through the estate tax.

Another reason that the increase in the reunified exemption is particularly useful to very wealthy individuals relates to the $13,000 annual gift exclusion. Consider Mr. and Mrs. Brown, a wealthy married couple with two children, Katie and John, both of whom are married. Every year, Mr. and Mrs. Brown can each give an amount up to the annual gift exclusion to each child and each child’s spouse, all tax-free. So in 2011, the Browns (between them) can give $26,000 to Katie and another $26,000 to Katie’s husband, for a total of $52,000. They can do the same for John and his wife. In total, that’s $104,000 that they can gift to their children’s families without triggering the gift tax or using any of their exemption. If Mr. and Mrs. Brown expect to live for at least another ten years, they can plan on handing down more than $1 million without using any of their lifetime gift tax exemption.

While death may be certain, its timing is not. Most individuals who expect to live at least several more years have little incentive to make gifts that exceed the annual gift exclusion, since they presumably will be able to gift additional amounts in future years without using up any of their exemption. Because of this, most people are unlikely ever to use up their full gift tax exemption. In contrast, people who expect to have particularly large estates cannot only gift up to the annual gift exclusion each year but can give gifts far beyond that consisting of more rapidly appreciating assets, and thereby use the change in gift tax rules to further shrink their tax obligations.

New Estate Tax Rules Are Unaffordable

Not only does the estate tax provision of the tax-cut compromise provide unnecessary largesse to the wealthiest estates in the country, but it is also costly. The Joint Tax Committee estimates the cost at $68 billion compared to letting the pre-2001 rules return. [9] We estimate it would have cost about $23 billion less to reinstate the 2009 rules for the same time period. Moreover, if extended over ten years, the new rules would cost about another $80 billion more than maintaining the 2009 rules over that period.

Providing tens of billions of dollars in new tax windfalls to the largest one-quarter of 1 percent of estates would be difficult to justify in the best of times. It would be particularly gratuitous in the current fiscal context, when policymakers are starting to make substantial cuts in a range of government functions and are talking of deep cuts in areas ranging from education to infrastructure to Medicare to programs that help the poorest Americans meet basic necessities.

End Notes

[1] Tax Policy Center, “Taxable Estates, Estate Tax Liability, and Average Estate Tax Rate, By Size of Gross Estate, 2011,” December 8, 2010, http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/numbers/Content/PDF/T10-0269.pdf.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid. We follow the Tax Policy Center definition of a small business or farm estate as one in which more than half of the value of the estate is in a farm or business and the farm or business assets are valued at up to $5 million.

[4] Estates of people who died in 2010 have a choice between the 2010 rules put in place in 2001, under which the estate tax is repealed but capital gains are not forgiven, and the 2011 rules, under which there is an estate tax but capital gains are forgiven.

[5] James Poterba and Scott Weisbenner, “The Distributional Burden of Taxing Estates and Unrealized Capital Gains At the Time of Death,” NBER, July 2000, p. 19.

[6] Eric Toder, “Who Pays the Capital Gains Tax?,” Tax Notes, August 4, 2008, http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/UploadedPDF/1001201_Capital_gains_tax.pdf .

[7] Tax Policy Center, “Revenue Impact of Various Estate Tax Reform Proposals, 2010-2019,” October 27, 2009, http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/numbers/Content/PDF/T09-0431.pdf.

[8] Tax Policy Center, “Taxable Estates, Estate Tax Liability, and Average Estate Tax Rate, By Size of Gross Estate, 2011,” December 8, 2010, http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/numbers/Content/PDF/T10-0269.pdf.

[9] Joint Committee on Taxation, “Estimated Budget Effects of the ‘Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance Reauthorization, and Job Creation Act of 2010,’ Scheduled for Consideration by the United States Senate,” December 10, 2010, http://jct.gov/publications.html?func=download&id=3715&chk=3715&no_html=1 .