- Home

- Ryan Medicaid Block Grant Would Cause Se...

Ryan Medicaid Block Grant Would Cause Severe Reductions in Health Care and Long-Term Care for Seniors, People with Disabilities, and Children

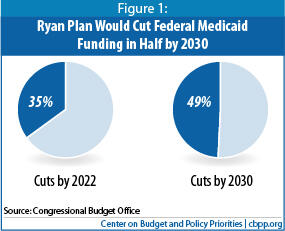

House Budget Committee Chairman Paul Ryan’s budget plan, which the House passed on April 15, would dramatically restructure Medicaid by converting it to a block grant and cutting the program’s funding sharply. According to the Congressional Budget Office, the Ryan budget would reduce federal funding by 35 percent in 2022 and by 49 percent in 2030, compared to what the funding would otherwise be. This would almost certainly affect tens of millions of low-income Medicaid beneficiaries adversely over time.

To compensate for the steep reductions in federal funding, states would either have to contribute far more in their own funds, or, as is much more likely, exercise the new flexibility under the block grant to cap enrollment, substantially scale back eligibility, and curtail benefits for seniors, people with disabilities, children, and other low-income Americans who rely on Medicaid for their health care coverage. To cite just a few examples of how different groups could be affected:

- Seniors: An overwhelming majority of Medicare beneficiaries who live in nursing homes rely on Medicaid for their nursing home coverage. Because the Ryan plan would require such deep cuts in federal Medicaid funding, it would inevitably result in less coverage for nursing home residents and shift more of the cost of nursing home care to elderly beneficiaries and their families. A sharp reduction in the quality of nursing home care would be virtually inevitable, due to the large reduction that would occur in the resources made available to pay for such care.

- People with disabilities: These individuals constitute 15 percent of Medicaid beneficiaries but account for 42 percent of all Medicaid expenditures, mostly because of their extensive health and long-term care needs. Capping federal Medicaid funding would place significant financial pressure on states to scale back eligibility and coverage for this high-cost population, many of whom would be unable to obtain coverage elsewhere because of their medical conditions.

- Children: Currently, state Medicaid programs must provide children with health care services and treatments they need for their healthy development through the Early Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment (EPSDT) aspect of Medicaid, which provides regular preventive care for children and all follow-up diagnostic and treatment services that children are found to need. A block grant would likely permit states to drop EPSDT coverage, meaning that children, particularly those with special health care needs, would not be able to access some care that medical professionals find they need (because Medicaid would no longer cover certain health services and treatments for children, and their parents wouldn’t be able to afford to pay for that care on their own).

- Working parents and pregnant women: Many state Medicaid programs already have extremely restrictive eligibility criteria for parents. In the typical state, working parents are ineligible for Medicaid if their income exceeds 64 percent of the poverty line (or $14,304 a year for a family of four), and unemployed parents are ineligible if their income exceeds 37 percent of the poverty line ($8,270 a year for a family of four). Under a block grant, states could cut these already low eligibility levels even further, cap enrollment, and/or require low-income parents to pay more for health services. States could do the same for low-income pregnant women who rely on Medicaid for their prenatal care, resulting in them forgoing services that are critical to ensuring a healthy pregnancy.

Ryan Plan Would Make Deep Cuts In Federal Medicaid Funding

Under current law, the federal government pays a fixed percentage of a state’s Medicaid costs. In contrast, under a block grant, the federal government would pay only a fixed dollar amount each year. The state would be responsible for all costs that exceed the cap. [1]

The Ryan plan would convert Medicaid from an entitlement program to a block grant starting in 2013. States would receive a fixed allotment of federal funding that would be increased annually based only on population growth and inflation as measured by the Consumer Price Index. As a result, over the next ten years, federal Medicaid funding would rise about 3.5 percentage points per year less than under the current program (and roughly 4 percentage points per year less over the long run). The Ryan plan does not specify how the block grant amount would be determined in its first year, but typically Medicaid block grant proposals set the initial grant amounts at the actual amount of federal Medicaid funding states received in the prior fiscal year (in this case, 2012), plus the annual adjustment. [2]

These federal funding shortfalls could be even larger in certain years because the Ryan plan would not provide for automatic increases in Medicaid funding during recessions, epidemics, or in response to medical breakthroughs that improve health or save lives but at greater expense. [5] According to CBO, the Ryan plan would “make funding for Medicaid more predictable from a federal perspective, but it would lead to greater uncertainty for states as to whether the federal contribution would be sufficient during periods of economic weakness.” [6]

Ryan Plan Would Likely Eliminate Most or All Medicaid Protections for Beneficiaries

Under current law, states must meet certain requirements in their Medicaid programs in order to receive federal funding. For example, any person who meets the program’s eligibility criteria is entitled to enroll in Medicaid; a state cannot generally impose enrollment caps or establish a waiting list. States must also cover certain “mandatory” populations, including children up to age 6 in families with incomes up to 133 percent of the poverty line and older children in families whose incomes are up to 100 percent of the poverty line. Federal law also requires states to cover certain “mandatory” benefits including hospital, nursing home, physician and home health care, and Early Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment (EPSDT), a comprehensive program of preventive care, screenings and treatment for low-income children. States also generally cannot charge premiums and can require only modest co-payments since most beneficiaries have very low incomes.

While states must meet these minimum federal requirements, they also have significant flexibility in the way they structure their Medicaid programs. For example, states have the flexibility to cover additional populations and cover optional benefits, such as prescription drugs and dental and vision services. In fact, about 60 percent of state Medicaid spending is optional in that it consists of expenditures for the coverage of people and/or benefits that federal law does not require states to provide. [7] States also have flexibility in setting reimbursement rates for health care providers and managed care plans that serve Medicaid beneficiaries. As a result, there is significant variation across state Medicaid programs in eligibility, benefits, cost-sharing requirements, and provider reimbursement rates.

Consistent with past block grant proposals, the Ryan plan would likely give states far greater flexibility to bypass many or all of the federal minimum standards on eligibility and benefits. For example, states would likely be permitted to limit income eligibility for various populations to very low levels, such as 50 percent of the poverty line, or eliminate coverage of certain beneficiary groups altogether. Alternatively, states could be allowed to cap enrollment. This is a vast departure from current Medicaid rules in which states are required to enroll any eligible individual who applies for coverage. States also likely would be allowed to charge much higher premiums and co-payments to beneficiaries or no longer cover mandatory benefits.

Some states may believe they can exercise their greater flexibility under the Ryan block grant to make their programs more cost-effective, without unduly cutting eligibility, benefits, or provider payments. As CBO notes, however, such hopes would very likely prove unrealistic, given the magnitude of the federal funding cuts, and states would have to deeply cut eligibility, benefits, and/or provider reimbursement rates over time.

How Would the Ryan Block Grant Likely Affect Seniors?

Under federal law, states generally must cover poor seniors who receive federal Supplementary Security Income (SSI) benefits. [8] The federal SSI income limit for elderly individuals is about 76 percent of the poverty line, or about $8,328 in 2011. (States have the option of providing coverage to seniors with somewhat higher incomes, and many do. In 2007, a little more than half of seniors enrolled in Medicaid were optional beneficiaries.) Approximately 6 million low-income seniors are “full dual eligibles” — people enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid. For those individuals, Medicaid fills the gaps in Medicare coverage, which these beneficiaries could not afford to fill on their own.

For many of these seniors, the long-term care benefits that Medicaid provides (and that Medicare does not cover) are particularly critical. An overwhelming majority of Medicare beneficiaries who live in nursing homes rely on Medicaid for their nursing home coverage. Because the Ryan plan would require such severe reductions in federal Medicaid funding, it would inevitably result in less coverage for nursing home residents and shift more of the cost of nursing home care to elderly beneficiaries and their families. While states are unlikely to eliminate coverage of long-term care services altogether, it would likely be a target for substantial cuts when a state’s block-grant funding becomes inadequate because these services are expensive and constitute about one-third of total Medicaid expenditures. [9]

Under a block grant, states might try to limit Medicaid expenditures for long-term care in various ways. For example, they could reduce income eligibility levels for seniors, resulting in a loss of nursing home and other long-term services and supports to many low-income seniors. States also could place a cap on the enrollment of seniors who require long-term care and establish waiting lists, just as they impose limits on the number of participants in their home and community-based waiver programs. Alternatively, states could cut back the care for which seniors in nursing homes are covered, by limiting the scope and/or duration of covered services, which would then lead nursing homes to curtail those services.

Seniors also could be charged cost-sharing for long-term care services and supports that many would have great difficulty affording. Under current law, Medicaid beneficiaries in hospitals, nursing homes, and other medical institutions already are required to contribute all but a nominal amount of their income for their care (beneficiaries are allowed to retain at least $30 per month for personal needs), and then are exempt from additional cost-sharing, as are patients receiving hospice care. Eliminating these cost-sharing protections would cause serious hardship among many seniors and their families and likely result in the loss of nursing home care — or of key nursing home services — for many seniors who simply wouldn’t be able to afford this care on their own.

In addition to long-term care, Medicaid is required to cover various acute care health services that Medicare does not cover or covers to a lesser extent than Medicaid, such as home health care. And, through the Medicare Savings Programs, state Medicaid programs also are required to help certain low-income Medicare beneficiaries pay their Medicare premiums and/or cost-sharing, which can be quite costly. [10] Facing severe reductions in their federal Medicaid funding, some states likely would elect to drop this coverage entirely or severely curtail it. (By 2022, when the Medicare program would be converted to a voucher under the Ryan budget, states would be prohibited from using federal Medicaid funding to cover acute-care services for Medicare beneficiaries, even if they wanted to continue doing so. The Ryan plan also would eliminate all Medicaid assistance in helping low-income Medicare beneficiaries pay their Medicare premiums and cost-sharing charges, replacing that assistance with medical savings accounts that would fall far short of covering these costs for low-income beneficiaries who are ill or have various medical conditions and thus need more health care.)[11]

How Would the Ryan Plan Likely Affect People with Disabilities?

States also generally must cover people with disabilities who receive SSI. People with disabilities constitute 15 percent of Medicaid beneficiaries but account for 42 percent of Medicaid expenditures. They have extensive health care needs and rely more on long-term care services and support, of which Medicaid is the primary funder. Many disabled beneficiaries are also dual eligibles who rely on Medicaid to fill in gaps in their Medicare coverage.

Capping federal Medicaid funding would place significant financial pressure on states to scale back coverage for this high-cost population in spite of their significantly greater needs. States could scale back eligibility or cap enrollment, two of the options described above. Either action would likely add disabled individuals with substantial health and long-term care needs to the ranks of the uninsured or underinsured. Because many people with disabilities on Medicaid are unable to work, they do not receive employer-based coverage, the primary source of health care coverage for most non-elderly Americans. In addition, these individuals generally are precluded from purchasing coverage in the individual insurance market or cannot afford such coverage because of current insurance underwriting rules (under which insurers charge prohibitive premiums for coverage that is offered to such individuals, if the individuals can even get an offer of insurance at all). [12] For these individuals, Medicaid is often the only health insurance option.

Even if some people with disabilities were able to obtain coverage elsewhere (which is highly unlikely), the benefits would be unlikely to cover their needs adequately. Private insurance plans typically are designed for healthy working populations. Services that people with disabilities rely on the most, such as mental health and rehabilitation services, often are covered to a limited degree or excluded altogether. In contrast, the coverage that Medicaid provides, which includes things like case management, therapeutic services, and personal care, is tailored to meet the needs of low-income people with severe disabilities, chronic illnesses, or other complex health conditions.

Many of the services that Medicaid beneficiaries with disabilities rely on are services that states are allowed but not required to offer, but states cover these services both because they help prevent subsequent complications that may create a need for more expensive care and because they help people with disabilities live in the community rather than having to be institutionalized. For example, rehabilitative services are an optional benefit, but nearly every state (47 states plus the District of Columbia) covers them for Medicaid beneficiaries. In 2004, some 1.5 million people received rehabilitative services through Medicaid, according to a report from the Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured. These optional services would be likely targets for cuts under the Ryan plan because of the deep federal funding reductions that would ensue.

States also could limit the availability of long-term care services and supports for people with disabilities who remain on the program. As discussed above, states could decide to cap enrollment among those requiring nursing home care or home health care, as they now do with home and community-based care programs. People with disabilities might also have to pay substantial deductibles and co-payments for services, including services that allow them to live independently, as well as premiums that they either could not afford or could pay only by failing to cover other necessities.

How Would the Ryan Plan Likely Affect Children?

Nowhere is Medicaid’s positive impact more evident than in the area of children’s coverage. This population is relatively inexpensive to insure but constitutes the largest group of Medicaid beneficiaries. Nearly 30 million children are insured through Medicaid today, accounting for approximately half of all program enrollees. Nationally, one-quarter of all children and more than half of all low-income children receive their health care through Medicaid.

Ryan Budget Would Repeal Health Reform’s Medicaid Expansion and Leave Millions Uninsured

Under the Affordable Care Act, state Medicaid programs will be required to cover all non-elderly individuals up to 133 percent of the poverty line ($24,700 for a family of three) starting in 2014. In most states, the expansion will allow non-disabled childless adults to become eligible for Medicaid for the first time. Moreover, because parents are covered to only a very limited extent — working parents are eligible only up to 64 percent of the poverty line in the typical state — many low-income parents will also gain Medicaid coverage. (Children would already be eligible under Medicaid and CHIP.) According to CBO, by 2021, some 17 million more people will be enrolled in Medicaid than would have been the case under prior law. The Medicaid expansion is one of the main reasons that CBO expects the Affordable Care Act to reduce the number of uninsured people by an estimated 34 million by 2021.

In addition to converting Medicaid into a block grant, the Ryan budget plan would repeal the health reform law’s Medicaid expansion. This would mean that millions of low-income uninsured parents and childless adults would remain without health coverage. Moreover, research demonstrates that children eligible for Medicaid and CHIP are more likely to enroll and access needed preventive and acute care services when their parents are also insured. The repeal of the Medicaid expansion would likely result in many low-income eligible children in families with uninsured parents remaining uninsured or continuing to go without the care they need to ensure their healthy development.

Federal law requires states that participate in Medicaid to cover children up to age 6 with family incomes up to 133 percent of the poverty line and older children whose family incomes are up to 100 percent of the poverty line, although most states have opted to cover children at higher income levels. Together with the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), Medicaid has played a central role in reducing the number of uninsured children as states expanded eligibility for this population and stepped up outreach efforts over the last decade. This progress was made even as employer-sponsored insurance continued to erode and the ranks of the uninsured increased.

In fact, during the most recent recession, Medicaid and CHIP were instrumental in preventing the ranks of uninsured children from swelling. In 2009, Medicaid and CHIP coverage for children grew by 3.5 percentage points to offset a 3.1 percentage point decline in employer coverage for children. [13] In future recessions, however, Medicaid’s ability to compensate for the reduction in children covered through private insurance would be severely limited under the Ryan approach, because federal funding would no longer automatically increase during an economic downturn and states would be allowed to institute enrollment caps and roll back eligibility.

Children and families, in particular, would likely suffer the most from the use of enrollment caps. It is likely that the elderly and disabled have fairly stable income and circumstances, whereas the income of families with children tends to fluctuate more. A temporary increase in income could end up terminating a child’s Medicaid eligibility and put the child at the end of a waiting list. In contrast, under the current structure, a child who temporarily becomes ineligible is able to re-enroll in Medicaid immediately if the income of the child’s family falls and the child again meets the program’s eligibility requirements.

In addition, under the Ryan plan, it is likely that children would no longer be guaranteed services they need for their healthy development as currently are provided through Medicaid’s Early Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment component. EPSDT is a mandatory pediatric benefit designed to ensure that children receive regular preventive care and all follow-up diagnostic and treatment services they are found to need, including services that may not otherwise be covered by a state’s Medicaid program for adults. The EPSDT benefit is more comprehensive than the comparable children’s benefit under most private insurance plans and covers services such as physical and speech therapy, hearing services, and vision exams and eyeglasses. These benefits are of critical importance for children in Medicaid because those children tend to be in poorer health than children with private coverage and because their parents often cannot afford these services on their own. Some states would likely eliminate EPSDT under the block grant, with the result that many children, particularly those with special health needs, would forgo some needed care.

States also could charge substantial premiums and cost-sharing for children that many low-income families could find unaffordable. Under current law, children with incomes below 150 percent of the poverty line cannot be charged premiums or co-payments. [14] Research shows that even modest premiums can make it difficult for low-income people to enroll in Medicaid and keep their coverage. (One multi-state study of health insurance programs for low-income people found that higher premiums were associated with lower participation. Premiums set as low as 1 percent of a family’s income were estimated to lead to a 15 percent reduction in participation. Thus, if 67,000 people participate without premiums, a 1 percent premium would lead to an estimated participation of 57,000, a 15 percent reduction. Premiums of 3 percent would cause an estimated 50 percent drop-off in participation. [15])

Alternatively, states could charge low-income children co-payments in line with the co-payments that private insurers typically charge. Such co-payments could run about $15 to $30 per office visit. For low-income children who use a lot of health care services, these cost-sharing requirements would pose a substantial burden. Research shows that higher co-payments tend to cause low-income individuals to use less primary and preventive care.[16] Low-income children with chronic conditions and disabilities, in particular, may not seek care they need if they are charged the co-payments typical in most private plans. This could lead to complications that eventually require more expensive care, such as emergency room treatment or hospitalization.

Some states might also use their flexibility under a block grant to shift beneficiaries, including children, into the private insurance market, and offer their families a voucher to purchase coverage. That approach would have a highly adverse impact on many children. Medicaid costs substantially less per beneficiary than private insurance, largely due to its lower provider reimbursement rates and lower administrative costs. [17] As a result, the only way to shift beneficiaries into private insurance without raising state costs is to provide vouchers that offer considerably less coverage than Medicaid currently provides. The voucher amount that children and families would receive would likely be sufficient only for relatively scant coverage because states would also be dealing with large decreases in federal funds.

As mentioned previously, Medicaid provides coverage that is tailored to meet the needs of low-income children. Medicaid beneficiaries who are forced to buy private insurance using a voucher would likely lose access to important services such as EPSDT. In addition to losing coverage for such services, beneficiaries could also face hefty premiums and co-payments for services that the private insurance does cover; those charges tend to be considerably higher than the cost-sharing charges under the Medicaid program. (And as noted, Medicaid does not allow premium or cost-sharing charges at all for children below 150 percent of the poverty line, in order to avoid creating barriers to enrolling children or providing them access to needed care.)

How Would the Ryan Plan Likely Affect Parents and Pregnant Women?

Medicaid covers about 15 million low-income, non-elderly and non-disabled adults, most of whom are parents in working families. Although these parents have jobs, they often have few options for affordable insurance coverage — either their employers do not offer health coverage or their share of the premiums would take up a considerable portion of their income.

Many states already have extremely restrictive eligibility criteria for parents. The minimum income standard for Medicaid varies from state to state and is tied to the income guidelines that were in place to qualify for a state’s Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) program in 1996. In the typical (or median) state, working parents are ineligible for Medicaid if their income exceeds 64 percent of the poverty line (or $14,304 a year for a family of four) and parents without employment are ineligible if their income exceeds 37 percent of the poverty line ($8,270 a year for a family of four). In Arkansas and Louisiana, working parents who earn more than 17 percent of the poverty line ($3,800 for a family of four) and 25 percent of the poverty line ($5,588 for a family of four), respectively, are ineligible for Medicaid. Under a block grant, states could cut these already low eligibility levels further or cap enrollment, particularly when parents may need it most, such as during a recession. States also could charge low-income parents substantial premiums and cost-sharing that they could not afford and that would lead them to forgo needed care.

Pregnant women who rely on Medicaid for their prenatal care could end up forgoing services that are critical to ensuring a healthy pregnancy. Current law requires states to cover pregnant women up to 133 percent of the poverty line. Recognizing the importance of providing appropriate prenatal care to pregnant women, most states have expanded Medicaid eligibility: about half of the states cover pregnant women beyond the federal minimum income eligibility level, and about a third of the states cover pregnant women up to 185 percent of the federal poverty line.

Today, Medicaid is a key source of coverage for low-income pregnant women. Without Medicaid, many of these women would remain uninsured and would not have the resources to obtain prenatal care. Research has shown that babies born to women who do not receive adequate care are three times more likely to have a low birth weight — a leading cause of infant mortality — than babies born to women who receive prenatal care. [18] Prenatal care is also important in preventing birth complications that require more expensive treatment and in minimizing avoidable birth defects. By ensuring that low-income pregnant women have timely and adequate access to health care, Medicaid plays a major role in improving birth outcomes across the country.

A block grant would inevitably lead to rollbacks in Medicaid enrollment or eligibility that could result in coverage of fewer low-income pregnant women and reverse the progress made in improving birth outcomes. In the long run, this may prove to be more costly to the health care system, as uninsured low-income pregnant women who delay getting prenatal care or forgo prenatal care altogether may end up developing complications that could have been prevented.

Pregnant women also are generally not charged premiums and are currently exempt from cost-sharing for services relating to their pregnancy or for other medical conditions that may complicate their pregnancy. Some states could charge premiums and cost-sharing that low-income women could not afford. Such changes could lead to more costly and complex births and poorer health outcomes for the child.

Conclusion

Transforming Medicaid from a program that guarantees coverage to eligible individuals into a block grant, as the Ryan plan does, would have adverse consequences for millions of low-income Americans. Despite the promise of greater state flexibility, the principal choices states would have would concern how to distribute the cuts among the various vulnerable groups that the program serves.

The beneficiaries whom Medicaid serves — low-income seniors, people with disabilities, children, parents, and pregnant women — could lose coverage, have their benefits substantially scaled back, face out-of-pocket costs they have difficulty affording, or be forced to obtain private insurance that likely would provide inadequate benefits and charge much higher premiums and cost-sharing. For many of these beneficiaries, the options under the Ryan plan would be to go uninsured or to be substantially underinsured and forgo needed care.

End Notes

[1] For background on proposals to convert Medicaid to a block grant, see Edwin Park, “Medicaid Block Grant or Funding Caps Would Shift Costs to States, Beneficiaries, and Providers,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, January 6, 2011.

[2] Under our estimates, a Medicaid block grant based on federal fiscal year 2012 spending adjusted annually by inflation and population growth would produce about $500 billion in federal Medicaid funding reductions over ten years, not the $771 billion in Medicaid cuts that the Ryan plan contains. This could mean that the initial block grant amount would be set well below the prior year’s spending level or that the annual adjustment is even lower than described. See Edwin Park, “Medicaid Funding Formula Under Ryan Plan Likely Even Worse than Advertised,” Off the Charts Blog, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 12, 2011, http://www.offthechartsblog.org/medicaid-funding-formula-under-ryan-plan-likely-even-worse-than-advertised/.

[3] A small portion of the $771 billion in savings may also be due to the Ryan plan’s cap on liability for medical malpractice. The Ryan budget would also repeal the health reform law’s Medicaid expansion (and the $627 billion in additional federal funding to cover nearly all of the expansion’s costs) for a total cut to Medicaid of $1.4 trillion over the next ten years.

[4] Congressional Budget Office, “Long-Term Analysis of a Budget Proposal by Chairman Ryan,” April 5, 2011.

[5] See Edwin Park and Matt Broaddus, “Medicaid Block Grant Would Shift Financial Risks and Costs to States,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 23, 2011.

[6] Congressional Budget Office, op cit.

[7] See, for example, Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, “Medicaid: An Overview of Spending on ‘Mandatory’ vs. ‘Optional’ Populations and Services,” June 2005.

[8] Thirteen states are so-called “209(b)” states, which are allowed to maintain more restrictive standards for covering low-income seniors and people with disabilities.

[9] Kaiser State Health Facts, “Distribution of Medicaid Spending by Service, Fiscal Year 2009,” Kaiser Family Foundation 2011, http://www.statehealthfacts.org/comparetable.jsp?ind=178&cat=4.

[10] Medicaid pays premiums, deductibles, and co-insurance on behalf of Medicare beneficiaries with incomes below the federal poverty line. Beneficiaries with incomes between 100 percent and 135 percent of the poverty line receive help through Medicaid only with their premiums.

[11] January Angeles, “Out-of-Pocket Medical Costs Would Skyrocket for Low-Income Seniors and People with Disabilities Under the Ryan Budget Plan,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, April 15, 2011.

[12] The Ryan budget plan would also eliminate the new health insurance exchanges to make it easier for individuals to purchase coverage on their own, as well as the premium and cost-sharing subsidies to help low- and moderate-income individuals afford exchange coverage.

[13] Arloc Sherman et al., “Census Data Show Large Jump in Poverty and the Ranks of the Uninsured in 2009,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, September 17, 2010.

[14] Those above 150 percent of the poverty can be charged premiums and co-payments (with certain limits) so long as they do not exceed in aggregate 5 percent of the family’s income.

[15] Leighton Ku and Teresa Coughlin, “Sliding-Scale Premium Health Insurance Programs: Four States’ Experiences,”

Inquiry 36: 471-480 (Winter 1999-2000). In this study, the low-income criteria varied for each state’s program.

[16] The research on cost-sharing and premiums is summarized by Julie Hudman and Molly O’Malley, “Health Insurance Premiums and Cost-Sharing: Findings from the Research on Low-Income Populations,” Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured, March 2003.

[17] Leighton Ku and Matthew Broaddus, “Public and Private Insurance: Stacking Up the Costs,” Health Affairs (web exclusive), June 24, 2008. See also Jack Hadley and John Holahan, “Is Health Care Spending Higher Under Medicaid or Private Insurance?,” Inquiry 40: 323-342, Winter 2003/2004.

[18] Department of Health and Human Services, Maternal and Child Health Bureau, “A Healthy Start, Begin Before Baby’s Born,” http://www.mchb.hrsa.gov/programs/womeninfants/prenatal.htm.