Statement: Chad Stone, Chief Economist, on the November Employment Report

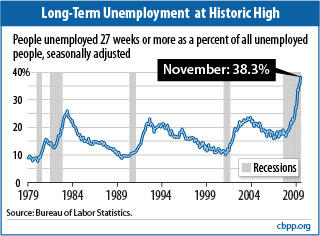

Today’s report that the pace of job losses has dramatically abated is the most encouraging in a long time, but serious problems remain for unemployed job-seekers. The number of people who have been unemployed for 27 weeks or more continued to climb in November, and these long-term unemployed now are nearly 40 percent of total unemployment (see chart). Renewing the temporary assistance for unemployed workers scheduled to expire in less than a month and providing additional federal fiscal assistance to states remain at the top of the list of measures that policymakers should take to help jobless workers and speed the economic recovery.

The pace of job losses due to layoffs and business closings is abating, the recent evidence suggests. But a labor market recovery that puts unemployed workers back to work requires faster growth in demand and a much greater pace of new hires than is yet evident. The economy must also overcome a significant barrier: the drag on growth and job creation from further state budget tightening. We estimate that without additional federal assistance, state actions to close their projected budget deficits could cost the economy 900,000 jobs next year.

The temporary additional weeks of benefits and other assistance for unemployed workers in the recovery legislation that the Administration and Congress enacted earlier this year have not only helped relieve the hardship faced by the long-term unemployed and their families, but they have also provided a boost to economic activity and job creation. Extending these measures into 2010 should be a “no-brainer” for policymakers: helping unemployed workers isn’t an alternative to preserving and creating jobs; it’s one of the most effective ways to preserve and create jobs. The same is true for state fiscal relief. These measures consistently rank very high in economists’ assessments of bang-for-the-buck impact in boosting demand and creating jobs.

About the November Jobs Report

The headline numbers on unemployment and payroll employment in today’s jobs report are encouraging, while some of the details in the report remain troubling.

- Private and government payrolls combined shrank by just 11,000 jobs in November and earlier estimates of losses in September and October were revised down sharply. Nevertheless, payroll employment has declined for 23 straight months and net job losses since the recession began in December 2007 total 7.2 million. (Private sector payrolls have shrunk by 7.3 million jobs over the period.) Each February, the Labor Department’s Bureau of Labor Statistics issues revisions to its payroll employment statistics based on more complete information, and preliminary estimates indicate these revisions could add about another 800,000 job losses to these figures.

- The pace of job losses has slowed markedly — to an average of just 104,000 per month over the past three months, compared with 645,000 jobs per month lost over the November 2008 to April 2009 period.

- The unemployment rate, which was 4.9 percent at the start of the recession, stood at 10.0 percent in November, down from 10.2 percent in October. Potential job-seekers remained on the sideline, however, as labor force participation edged down to 65.0 percent. It has not been lower since January 1986.

- The decline in labor force participation was offset by higher household employment, and the percentage of the population with a job was unchanged at 58.5 percent, its lowest level since October 1983.

- The Labor Department’s most comprehensive alternative unemployment rate measure — which includes people who want to work but are discouraged from looking and people working part time because they can’t find full-time jobs — edged down to 17.2 percent in November. That figure is 8.5 percentage points higher than when the recession began, and with the exception of last month is the highest on record in data that go back to 1994.

- Nearly two-fifths (38.3 percent) of the 15.4 million people who are unemployed have been looking for work for 27 weeks or longer. That’s the highest percentage on record in data going back to 1948. Regular unemployment insurance benefits typically run out after 26 weeks.

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities is a nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization and policy institute that conducts research and analysis on a range of government policies and programs. It is supported primarily by foundation grants.