- Home

- State Earned Income Tax Credits: 2010 Le...

State Earned Income Tax Credits: 2010 Legislative Update

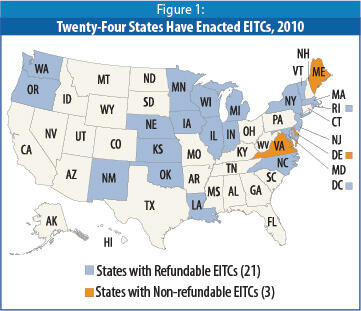

An Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) modeled on the federal program of the same name is now offered in 23 states and the District of Columbia as a way to reduce taxes and supplement wages for low- and moderate-income working families. A large body of evidence has shown that the state and federal EITCs serve a number of important public policy goals. States that enact EITCs can reduce child poverty, cut taxes for low-income families, and increase the incentive to work.

Rising Number of States Offer EITCs

Since 2006, five states have enacted EITCs — Michigan in 2006; North Carolina, Louisiana, and New Mexico in 2007; and Washington in 2008 — bringing the total number of states with an EITC to 24. New Mexico and North Carolina followed up in 2008 by expanding their recently enacted credits, and in 2010, Kansas increased slightly the value of its credit.

When these new and expanded EITCs are fully implemented, nearly two out of five recipients of the federal EITC will live where a state EITC is available and annual state EITC benefits will exceed $2.5 billion.

The recent recession sharply reduced state revenues. This in turn has lessened states’ ability to finance new EITCs or EITC expansions, and in a few cases states cut back on credits. In 2010, New Jersey reduced its credit to 20 percent from 25 percent of the federal credit. Iowa and Virginia cut benefits by not conforming to expansions of the federal EITC enacted under the Recovery Act. Washington enacted a credit in 2008 but postponed implementation until tax year 2012.

Notwithstanding current state fiscal problems and some states’ actions to scale back their credits, state EITCs continue to receive broad backing. EITCs have been enacted by states with Republican, Democratic, and bipartisan leadership, and the credits are supported by business groups, labor, faith-based organizations, and social service advocates.

Why Consider an EITC?

Several developments explain the utility of state EITCs.

- Continued child poverty and economic hardship. Many children in working families live in poverty —some 8 million in 2008. And many families with incomes modestly above the federal poverty line, currently around $22,000 for a family of four, also face significant difficulty in meeting the costs of food, housing, transportation, clothing, and other necessities. Sluggish wage growth for low-earning families means that many are likely to continue to struggle. The federal EITC alone lifted about 6.5 million people — including 3.3 million children — above the poverty line in 2009; it is the nation’s most effective anti-poverty program for working families.[1]

- State EITCs serve to supplement the impact of the federal EITC.

- Low wages and welfare changes. Wage and salary growth has been weak throughout this decade and has been weakened further by the current national recession. Since the welfare overhaul in the mid-1990s, most of the several million people who left welfare and became employed make low wages. A full-time job at the minimum wage often is not sufficient to lift a family out of poverty. Concern about the impact of low pay on working families has led a number of states and the federal government to raise minimum wages in recent years. But even with those increases, low-wage jobs often do not provide sufficient income on which to live. State EITCs support families who enter and remain in the workforce.

- Tax inequities. In most states, low- and moderate-income families pay higher state and local taxes as a share of their income than do upper-income families. This imbalance results from states relying heavily on sales, excise, and property taxes, which fall heavily on poorer families. Some states are increasing these regressive taxes, potentially affecting working families disproportionately. A state EITC can help offset the impact of such taxes. (This, in fact, explains the 2010 Kansas increase; it was added to legislation that included a sales tax increase.)

- EITCs encourage work . Empirical research repeatedly confirms that both the federal and state EITCs increase workforce participation among eligible families. Expansion of existing state EITCs increases this effect.[2]

- EITCs are used for asset-building expenditures. Research interviews conducted with EITC recipients show that many use their EITC refunds to make the kinds of investments — paying off debt, obtaining education, securing decent housing — that enhance economic security and promote opportunity. [3]

How Does the EITC Work?

State EITCs are simple to implement, administer, and claim. They typically “piggyback” on the federal EITC, meaning that they mostly have the same eligibility requirements and are set at a fixed percentage — between 3.5 percent and 40 percent — of the credit that recipients receive from the federal program. As a result, states can take advantage of the existing federal statutory structure and compliance apparatus, and filers need only multiply their federal EITC by a specified rate to determine their state credit.

The federal EITC was established in 1975 in recognition of the fact that federal payroll taxes cost low-income families a substantially higher share of their income than is the case for middle- and upper-income families. The EITC helps to offset this impact. Expanded several times over the past 35 years, the federal EITC provides additional assistance to persons newly entering the workforce and workers who are supporting their families on low wages.

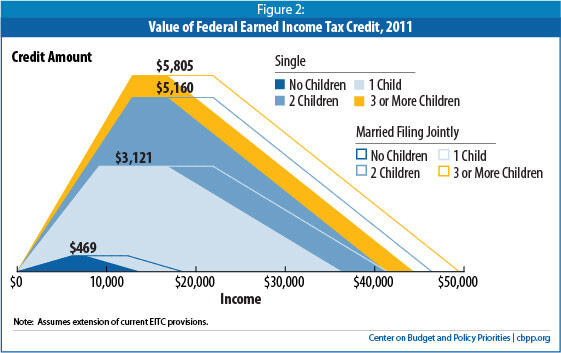

The EITC’s design reflects the reality that larger families face higher living expenses than smaller families. As shown in Figure 2, the maximum federal benefit for families with two children in tax year 2011 is $5,160. For families with one child the maximum is $3,121. Workers without a qualifying child can also receive an EITC, but at a much lower amount. The maximum credit for individuals or couples without children is $469 in 2011. (As with most other provisions of the federal tax code, EITC benefit amounts and eligibility levels are adjusted each year by the IRS for inflation.)

For families with very low earnings, the dollar amount of the EITC increases as earnings rise. For example, families with two children receive a credit equal to 40 cents for each dollar earned up to $12,900, for a maximum benefit of $5,160. Families with one child receive an EITC equal to 34 cents for each dollar up to $9,180 of earnings, for a maximum benefit of $3,121. Families continue to be eligible for the maximum credit until income reaches $16,840 (or $21,970 for married-couple families), after which the amount they receive goes down until it reaches zero when family income surpasses the eligibility level.

For single-parent families with two children, eligibility for the EITC ends when income exceeds $41,341. Families with one child remain eligible until their income exceeds $36,372. For married couples, eligibility for the credit ends when income exceeds $46,471 for those with two children and $41,502 for those with one child.

Working families with incomes below the federal poverty line receive the largest benefits. However, because the EITC phases out gradually as income rises, many families with incomes well above the poverty line still benefit to some degree.[4]

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) adopted in February 2009 included two key provisions to help the EITC go further. Expanding a provision first enacted in the 2001 tax cuts, ARRA increased the EITC income eligibility level for married workers, thereby extending eligibility for the maximum credit to a greater number of married couple working families with low-incomes.

ARRA also provided, for the first time, a third benefit tier for larger families. If these expansions are extended, families with three or more children in 2011 will receive an EITC equal to 45 cents for each dollar earned up to $12,900, for a maximum credit of $5,805. Single-parent families with three or more children will reach their eligibility limit when their income exceeds $44,404; married couple families of this size will reach their eligibility limit at $49,534.

Under current law, both the higher income thresholds for married couples and the “third tier” for families with three or more children are scheduled to expire after the 2010 tax year. If this occurs, married couples will qualify for the same benefits as unmarried tax filers, and families with three or more children will qualify for the same benefits as those with two children. The Obama Administration has proposed making both of these features permanent.

Designing a State EITC

| Table 1: State Earned Income Tax Credits | ||

| State | Percentage of Federal Credit (Tax Year 2010 Except as Noted) | Refundable? |

| Delaware | 20% | No |

| District of Columbia | 40% | Yes |

| Illinois | 5% | Yes |

| Indiana | 9% | Yes |

| Iowa | 7% | Yes |

| Kansas | 18% | Yes |

| Louisiana | 3.5% | Yes |

| Maine | 5% | No |

| Marylanda | 25% | Yes |

| Massachusetts | 15% | Yes |

| Michigan | 20% | Yes |

| Minnesotab | Average 33% | Yes |

| Nebraska | 10% | Yes |

| New Jersey | 20% | Yes |

| New Mexico | 10% | Yes |

| New Yorkc | 30% | Yes |

| North Carolinad | 5% | Yes |

| Oklahoma | 5% | Yes |

| Oregone | 6% | Yes |

| Rhode Island | 25% | Partiallyg |

| Vermont | 32% | Yes |

| Virginia | 20% | No |

| Washington | Not yet implemented; scheduled to be 10% in 2012f | Yes |

| Wisconsin | 4% — one child 14% — two children 43% — three children No credit for childless workers | Yes |

| Notes: From 1999 to 2001, Colorado offered a 10% refundable EITC financed from required rebates under the state’s “TABOR” amendment. Those rebates, and hence the EITC, were suspended beginning in 2002 due to lack of funds and again in 2005 as a result of a voter-approved five-year suspension of TABOR. In 2011 when the TABOR suspension expires and given sufficient revenues, rebates will resume. A new law passed in 2010, however, would prioritize EITC refunds over rebates and over use of surplus revenues to fund an income tax cut also scheduled for 2011. a Maryland also offers a non-refundable EITC set at 50 percent of the federal credit. Taxpayers in effect may claim either the refundable credit or the non-refundable credit, but not both. b Minnesota’s credit for families with children, unlike the other credits shown in this table, is not expressly structured as a percentage of the federal credit. Depending on income level, the credit for families with children may range from 25 percent to 45 percent of the federal credit; taxpayers without children may receive a 25 percent credit. c Should the federal government reduce New York’s share of the TANF block grant, the New York credit would be reduced automatically to the 1999 level of 20 percent. d North Carolina's EITC is scheduled to expire in 2013. e Oregon's EITC is scheduled to expire at the end of 2013. f Washington’s EITC will likely be worth 10 percent of the federal credit or $50, whichever is greater. g Rhode Island made a very small portion of its EITC refundable effective in TY 2003. In 2006, the refundable portion was increased from 10 percent to 15 percent of the nonrefundable credit (i.e., 3.75 percent of the federal EITC) | ||

Of the 24 state EITCs, 21 are modeled directly on the federal EITC. Those 21 programs use federal EITC eligibility rules and offer a state credit that is a specified percentage of the federal credit. (The percentages are shown in Table 1.) Minnesota uses federal eligibility rules, and its credit parallels major elements of the federal structure; however, it has its own schedule for the income levels at which the credit phases in and phases out. Two other states, Iowa and Virginia, also use federal rules to determine eligibility for their state’s credit, but their credits are set as a percentage of the pre-2009 federal EITC benefit levels (adjusted for inflation). This means that the EITC changes enacted under ARRA do not carry through to these states’ EITCs.

Twenty state EITCs follow the federal practice of making the credit fully “refundable.” This means that the amount by which the credit exceeds annual income taxes is paid as a refund. A family with no income tax liability receives the entire EITC as a refund. In Rhode Island, the earned income credit is partially refundable—a family is eligible for only a portion of the amount by which the allowable credit exceeds its tax liability. All low-income working families with children can participate in a refundable EITC.[5]

The remaining three states — Delaware, Maine, and Virginia — offer non-refundable credits. Such credits are available only to the extent that they offset a family’s state income tax. A non-refundable EITC still can provide substantial tax relief to families with state income tax liability, but it offers no benefits to working families that have income too low to owe any income taxes. For these families, a non-refundable EITC does not reduce taxes. It assists somewhat fewer working-poor families with children and is likely to be less effective as a work incentive.

States Without an Income Tax Can Offer a State EITC

As with the federal EITC, state EITCs have a long, successful history of using the income tax as a mechanism for providing increased economic security to low-income working families. But there has been debate about whether a state that has no income tax could offer similar assistance. With no state income tax, state revenue departments do not typically collect the information about family income and structure needed to determine EITC eligibility. This produced concern that offering an EITC would require establishing a large new screening and enforcement effort. In becoming the first state without an income tax to enact an EITC, Washington has addressed this dilemma.[6]

Washington’s Working Families Tax Exemption, as enacted, will be straightforward to administer. To confirm eligibility, the state will use data on federal EITC claimants provided by the IRS to state revenue departments under a common data-sharing arrangement. Piggybacking on federal efforts saves Washington on enforcement, and, when the credit is fully phased in, state officials estimate that administration will constitute about 4 percent of the cost of its EITC.[7] If Washington were to increase the size of the credit, this share would be even smaller.

The other states with no broad-based income taxes (Alaska, Florida, Nevada, New Hampshire, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, and Wyoming) potentially could follow suit. Offering state EITCs in these states would benefit millions of low-income working families. State EITCs could be particularly helpful in these states where, due to regressive tax systems that rely heavily on excise taxes, property taxes, and in most cases sales taxes, low- and moderate-income families pay a higher share of their income in taxes than upper-income families.

Financing a State EITC

Enacting an EITC is relatively affordable. Existing refundable EITCs in states with income taxes produce a revenue loss of less than 1 percent of state tax revenues each year. Four factors affect the cost of a state EITC: the number of families that claim the federal credit, the percentage of the federal credit at which the state credit is set, whether the credit is refundable or non-refundable, and how many state residents that receive the federal credit also learn about and claim the state credit. Because state EITCs are targeted more specifically to low- and moderate-income working families than many other major tax cuts are, the cost may be relatively modest.[8] Though low-income households tend to comprise a substantial share of all taxpayers, the share of tax revenue they account for is much lower. A few hundred dollars for each family makes a big difference to the family’s ability to make ends meet without adding up to a major dent in a state’s treasury.

State EITCs are financed in whole or in part from money available in a state’s general fund — the same source usually used to pay for other types of tax cuts. When an EITC is used to offset the effects of increasing a regressive tax, like the sales tax, part of the new revenue can be set aside to finance the EITC. In effect, that helps make low-income families whole again after paying the higher sales tax. Current federal regulations also offer the opportunity to finance a portion of the cost of a refundable credit from a state’s share of the federal Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) block grant. Most states, however, have very limited availability of such funds, because the value of the TANF block grant has eroded over time. No matter how it is financed, an EITC can complement a state’s welfare program by assisting low-income working families with children.

Further details on state EITCs and how they can help working families escape poverty are available in a forthcoming report from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities: “A Hand Up: How State Earned Income Tax Credits Help Working Families Escape Poverty in 2012,” by Nicholas Johnson and Erica Williams. The report will be released in late 2010.

Stimulus Keeping 6 Million Americans Out of Poverty in 2009, Estimates Show

End Notes

[1]Center simulation of 2009 policies using Census data from the March 2004-2006 Current Population Surveys and other sources. For a description of the methods used, see Arloc Sherman, “Stimulus Keeping 6 Million Americans Out of Poverty in 2009, Estimates Show,” September 9, 2009.

[2] For a review of the research around the impact of the EITC on workforce participation, see Steve Holt, “The Earned Income Tax Credit at 30: What We Know,” The Brookings Institution, February 2006.

[3] Timothy M. Smeeding, Katherin Ross Phillips, and Michael O'Connor, “The EITC: Expectation, Knowledge, Use, and Economic and Social Mobility,” No 13, Center for Policy Research Working Papers.

[4] The 2011 federal poverty line is about $23,000 for a family of four.

[5] Since Washington lacks a personal income tax, the full value of its EITC will be refunded to those claiming it.

[6] The Washington credit was scheduled to take effect in tax year 2009, but its implementation requires an appropriation. Because of the recession and resulting revenue shortfalls, policymakers did not finance the credit for 2009. However, the state’s fiscal year 2011 budget appropriated administrative funds to prepare for full implementation in tax year 2012.

[7] Fiscal note for Washington ESSB 6809. Note that administrative cost in a state that already has an income tax would be substantially lower, typically well below 1 percent of credit value.

[8] For further information about estimating the cost of a state EITC see Erica Williams and Nicholas Johnson, “How Much Would a State Earned” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, November 24, 2010.

More from the Authors

Areas of Expertise