GAO Study Again Confirms Health Savings Accounts Primarily Benefit High-Income Individuals

End Notes

[1] Government Accountability Office, “Health Savings Accounts: Participation Increased and Was More Common among Individuals with Higher Incomes,” April 1, 2008.

[2] Government Accountability Office, “Consumer-Directed Health Plans: Early Enrollee Experiences with Health Savings Accounts and Eligible Health Plans,” August 8, 2006.

[3] See Government Accountability Office (2006), op cit and Edwin Park and Robert Greenstein, “GAO Study Confirms Health Savings Accounts Primarily Benefit High-Income Taxpayers,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, September 20, 2006.

[4] Government Accountability Office (2008), op cit.

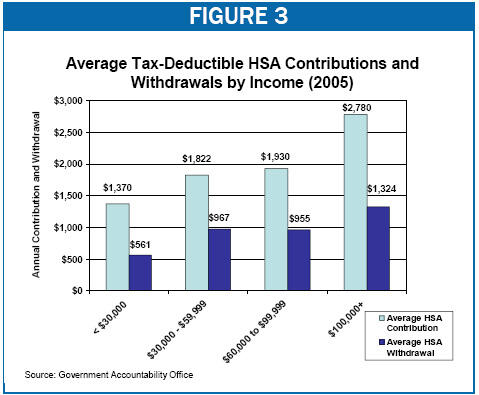

[5] Contributions include those made by individual tax filers as well as those made by employers or other individuals on their behalf, but do not include funds transferred from Medical Savings Accounts, precursors to Health Savings Accounts that are established as part of a demonstration project in 1996.

[6] It is likely that there are a number of individuals in this income range who may be enrolled in HSA-eligible high-deductible health plans but have not established or contributed to a HSA. According to GAO’s examination of employer surveys, more than 40 percent of individuals enrolled in a high-deductible health insurance plan eligible for a HSA did not open an HSA. Reasons cited by survey respondents included lack of information, lack of need and a belief that they could not afford to put money in the accounts. Government Accountability Office (2008), op cit.

[7] Health policy analysts and economists have expressed significant concern that high-deductible plans attached to HSAs risk “adverse selection.” Adverse selection occurs when healthy and less-healthy individuals separate into different health insurance arrangements, and the average cost of insurance for the less-healthy group rises significantly, because these people are no longer being pooled with healthier individuals who are less expensive to insure. When that occurs, premium costs for the less-healthy can rise sufficiently high that those individuals are put at risk of becoming uninsured or underinsured.

High deductible plans attached to HSAs are likely to be disproportionately attractive to healthier individuals who do not need much health care and thus are less concerned about the higher out-of-pocket costs that can result under a high-deductible plan in comparison to a more traditional lower-deductible plan. If healthier individuals move to HSA-eligible plans in large numbers over time while less healthy individuals remain in traditional plans, that could drive up health insurance premiums for the more traditional plans and make them increasingly unaffordable over time. The fact that a large proportion of individuals contributing to HSAs make no withdrawals may indicate not only that these individuals are using HSAs as tax shelters but also that they may be healthier, on average, and therefore have less utilization of health care services. This deepens the concern over adverse selection. For a discussion of why Health Savings Accounts may spur adverse selection, see Edwin Park and Robert Greenstein, “Latest Enrollment Data Still Fail to Dispel Concerns About Health Savings Accounts,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Revised January 30, 2006.

[8] John Dicken, “Health Savings Accounts: Participation Grew, and Many HSA-Eligible Plan Enrollees Did Not Open HSAs while Individuals Who Did Had Higher Incomes,” Testimony before the Subcommittee on Health, House Ways and Means Committee, Government Accountability Office, May 14, 2008. The GAO also noted that only 22 percent of tax filers making HSA contributions withdrew as much or more than their reported contributions. According to the GAO, industry experts viewed this minority population as consistent with HSA account holders who are “spenders” and who actually use these accounts to pay for out-of-pocket health care costs, rather than as a tax-preferred savings vehicle.