- Home

- Boosting Income And Contribution Limits ...

Boosting Income and Contribution Limits For Pension Savings Would Swell Deficits, Do Little For Middle-Class Families

Ways and Means Chairman Bill Thomas has suggested that new tax cuts to promote retirement savings should be considered as part of the effort to reform Social Security. Chairman Thomas has expressed interest in a range of proposals.[1]

A number of retirement-related tax proposals have strong proponents on Capitol Hill, in the financial securities industry, and among other interest groups. Among the proposals being pushed are measures to raise the amount that workers can contribute to employer-sponsored 401(k)s and Individual Retirement Accounts, to remove the income limits that apply to IRAs, and to create tax-sheltered accounts for health care costs incurred in retirement.

Most such proposals would be very costly, especially in future decades when the baby boomers will retire in large numbers and the nation faces deficits of unprecedented magnitude. In addition, most such proposals would provide the bulk of their tax benefits to high-income households that do not need help putting away enough money for retirement, while doing little or nothing to assist low- and moderate-income households to save more for retirement.

This analysis explores proposals to eliminate income limits on IRAs, raise contribution limits on IRAs and 401(k)s, and establish “health IRAs” or similar mechanisms.

Eliminating Income Limits on IRAs

Removing the income limits on IRAs is at the core of the Administration’s “Retirement Savings Accounts” proposal. The RSA proposal is contained in pension legislation that Rep. Rob Portman introduced before he left the House to become U. S. Trade Representative, and is likely to be considered for inclusion in a Social Security bill.

- The RSA proposal would be expensive, with the cost growing over time. Under RSAs, which are essentially Roth IRAs without an income limit, the revenue losses would occur when people retire and withdraw funds from their accounts tax-free, rather than when they make contributions to the accounts. As a result, the revenue losses would be small initially but would mount considerably over time.

- The Congressional Research Service estimated last year that the revenue loss would rise to about $9 billion a year after two decades. The Tax Policy Center estimates that over 75 years, the revenue loss from the RSA proposal would be equal to approximately 10 percent of the shortfall in the Social Security Trust Fund.[2] (RSAs could also result in state revenue losses; see box below.)

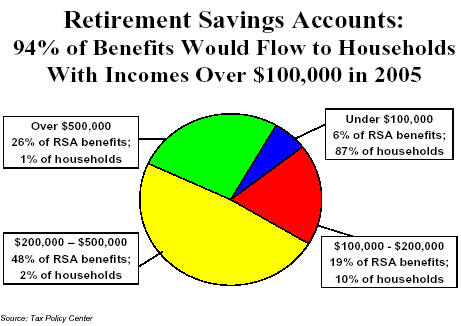

- Nearly all of the new tax breaks that the RSA proposal would provide would accrue to people at relatively high income levels. The Tax Policy Center has found that if the proposal were in effect in 2005, nearly three-quarters of its tax benefits — 74 percent — would go to the 3 percent of households with incomes over $200,000. Some 94 percent of the tax benefits would go to people with incomes over $100,000 (the top 13 percent of households). The concentration of these benefits should not be surprising, since the principal effect of the RSA proposal is to eliminate the income limits on Roth IRAs, which are set at $160,000 for married filers and $110,000 for single filers. (See the appendix for a description of IRA income limits and IRA and 401(k) contribution limits under current law.)

- Brookings economists William Gale and Peter Orszag have cautioned that removing the income limits on IRAs, as the RSA proposal would do, could lead small business owners to scale back employer retirement plans. They note that removing the income limits would make IRAs “available to many small business owners who are not currently eligible to make contributions to [IRA] accounts. These small business owners would then be able to scale back their employer-provided pension plans while still maintaining their own [total] contributions to tax-preferred savings accounts….[This] could result in reduced saving and coverage among rank-and-file workers.” For the same reason, Gale and Orszag explain, removing the IRA income limits “also could lead to less generous plans being established at new businesses than would otherwise be the case.”[3]

Raising Contribution Limits on IRAs and 401(k)s

People under 50 currently can make tax-deductible contributions of up to $14,000 a year to a 401(k). People 50 and over can contribute $18,000 a year. The $14,000 and $18,000 limits rise to $15,000 and $20,000 in 2006. These are the limits on employee contributions; firms can, and generally do, make substantial additional contributions to executives’ 401(k)s. There is no income limit on who can make tax-deductible contributions to 401(k)s.

People under 50 who are eligible for IRAs currently can contribute $4,000 a year ($8,000 for a couple). These limits rise to $5,000 ($10,000 for a couple) in 2008. People 50 and over can contribute somewhat more; starting in 2008, they will be able to contribute $6,000 ($12,000 for a couple).

These limits were raised substantially by the 2001 tax-cut legislation. Chairman Thomas is now reported, however, to be considering proposals to raise these limits still higher.

- Doing so would benefit only the small number of workers who already contribute the maximum amounts allowed. As a study conducted by a Treasury economist explained, taxpayers who do not contribute at the maximum “would be unlikely to increase their IRA contributions if the contribution limits were increased.”[4]

- Studies by the Treasury Department, the Congressional Budget Office, and the Employee Benefit Research Institute show that only about 5 percent of those eligible for IRAs contribute the maximum amount. Similarly, only about 5 percent of 401(k) participants make the maximum allowed contribution. A General Accounting Office study estimated in 2001 that increasing the contribution limits for 401(k)s would directly benefit fewer than three percent of participants.[5]

- Those aided would overwhelmingly be higher-income households. According to the CBO, only one percent of 401(k)s participants who earn less than $40,000 contributed the maximum amount in 1997. But 40 percent of those earning over $160,000 did.[6]

- Moreover, analyses by leading experts in the field indicate that those higher-income individuals who contribute the maximum amounts now and would deposit more into their 401(k)s or IRAs if the contribution limits were raised would, in general, simply shift savings from taxable accounts to tax-sheltered accounts rather than save more. As Brookings retirement expert Peter Orszag has observed, raising the contribution limits would provide large windfall gains to households already making the maximum contribution to tax-preferred accounts for saving they would have done anyway, with such households shifting other savings and assets into the tax-preferred accounts.[7]

- Finally, an increase in the IRA contribution limits could lead to fewer employers offering employer-sponsored retirement plans, and thus could reduce retirement saving by low- and middle-income workers. Currently, business owners and executives who want to put away more than $8,000 a year (for a couple) in tax-advantaged retirement savings must offer an employer-sponsored retirement plan that covers their workers, as well as themselves. If owners and executives were able to put away significantly larger amounts in tax-favored IRAs without having to offer an employer plan, more of them likely would do so. A Congressional Research Service study issued last year found that with a higher IRA contribution limit, “some employers particularly small employers, might drop their plans given the benefits of private savings accounts.”[8]

Health IRAs and Similar Tax Shelters

An array of tax-shelter proposals related to health care costs in retirement also could be considered for inclusion in a Social Security bill. Various proposals that have influential backers, such as Merrill Lynch or Fidelity, would allow people to make substantial tax-deductible contributions to investment accounts, receive earnings on the accounts that are sheltered from taxation, and then withdraw funds tax free in retirement as long as the amounts withdrawn do not exceed the retiree’s out-of-pocket health care costs in that year.

This group of proposals would obliterate what until now has been a fundamental principle of retirement tax policy: that tax-advantaged retirement accounts can feature either tax-deductible contributions or tax-free withdrawals, but not both. (The Health Savings Accounts established by the 2003 prescription-drug legislation include both tax-deductible contributions and tax-free withdrawals, but no retirement tax provisions include such a feature.)

The proposals in question include the following:

- So-called “individual health IRAs.” There are several types of such proposals. Under one type of health IRA, people making contributions to 401(k)s or IRAs would be allowed to designate a portion of their contributions to a health care “sub-account.” When the designated funds (and the earnings on them) were withdrawn in retirement, ostensibly for health care costs, the withdrawals would be entirely tax free even though the contributions had been tax deductible.

Under another type, the health IRA would be a new retirement saving vehicle on top of regular IRAs and 401(k)s, rather than as a part of existing IRAs and 401(k)s. People would be allowed to contribute to the health IRAs in addition to the contributions they make to other types of tax-advantaged retirement accounts. Those who could afford to contribute the most would gain the most.

Still another variant of this approach would allow withdrawals in retirement from regular, tax-deductible IRAs and 401(k)s to be tax free to the extent that the withdrawals did not exceed the cost of health insurance premiums in retirement. - Expanding Health Savings Accounts. Under this proposal, people with Health Savings Accounts could make tax-deductible contributions to those accounts over and above the large maximum contributions they already are allowed to make. The additional contributions (and the earnings on them) could be withdrawn tax free in retirement for health care costs.

These proposals would be very costly in future decades, when substantial sums that would otherwise be subject to tax would be withdrawn in retirement on a tax-free basis. Long-term budget projections, such as those made by CBO, GAO, and OMB, show massive budget deficits in future decades; those projections include about $3.8 trillion in revenue (in present value) which is slated to be collected on withdrawals from IRAs and 401(k)s between now and 2040. Health-related retirement tax proposals that would convert a portion of the withdrawals from tax-deductible IRAs and 401(k)s to tax-free status would likely result in a significant share of IRA and 401(k) withdrawals becoming tax free and thereby make the long-term fiscal picture markedly worse than it already is. (As discussed in the box on page 10, health IRAs also would reduce state revenues.)

In addition, these proposals would represent lucrative tax shelters for high-income people, who generally do not need increased government subsidies to meet their health care costs in retirement, while doing relatively little for retirees with modest incomes.

- These proposals would provide new tax shelter opportunities for high-income individuals who could afford to shift substantial sums from taxable investment accounts to tax-favored accounts on which deposits would be deductible and withdrawals in retirement would be tax free.

- But these proposals would do much less for ordinary families. A majority of low- and middle-income workers have neither an IRA nor a 401(k), and those who do have such accounts tend to have relatively modest account balances. In addition, low- and moderate-income families are in lower tax brackets than affluent households during their working years, so the upfront tax deductions for contributing large sums to such accounts are worth less to them. Most important, low- and moderate-income people generally owe no income tax or are in a low tax bracket in old age because their incomes decline after they stop working. As a result, the tax-free withdrawals these proposals offer would not be worth very much to them. The benefits of these new tax breaks would be heavily skewed to affluent retirees.

A Tax Deduction for Long-term Care Insurance

Another proposal expected to be considered for inclusion in a Social Security bill would provide a new tax deduction for the purchase of long-term care insurance. Such a deduction would be of little value to low- and middle-income families and would likely be ineffective in helping them secure long-term care insurance. Its benefits would disproportionately go to high-income individuals, who least need government subsidies to help them afford long-term care insurance.

- Long-term care insurance can be very expensive. The people for whom it is most out of reach are low- and middle-income families that do not earn enough to owe income tax or are in the 10 percent or 15 percent income tax brackets. About three-quarters of all tax filers fall into these categories.

Low-income families that do not earn enough to incur income tax liability would receive no benefit from the proposed deduction. For middle-class families in the 10 percent or 15 percent tax brackets, the deduction would defray no more than 10 cents to 15 cents of each dollar they would have to spend to purchase a long-term care insurance policy. The deduction thus would not make this insurance affordable for most of these people. - The deduction would be of greatest value to high-income taxpayers. The higher an individual’s tax bracket, the greater the subsidy the deduction would provide. For individuals in the highest tax bracket, the deduction would subsidize 35 percent of the cost of long-term insurance.

The proposal thus would consume a substantial amount of federal budget resources to provide new subsidies for long-term care primarily to Americans who least need such subsidies, while doing little to address the large long-term care costs that millions of ordinary Americans can encounter.

Indeed, low- and middle-income families could end up with less health care assistance under this proposal. It is likely they ultimately would have to bear a significant share of the burden of the higher deficits and debt these proposals would bring. The hefty revenue losses involved could intensify pressures for future budget cuts in programs such as Medicare and Medicaid. People of modest or ordinary means could lose more than they gained, while people at the top of the income scale reaped windfalls from a lucrative new tax shelter.

If Congress wishes to devote more resources to reducing the health care costs of retirees, it should do so transparently through the normal budget process. These proposals, by contrast, mask their true cost by using backloaded tax breaks to deliver health care subsidies, primarily to people with a questionable need for such subsidies.

Proposals Would Do Little To Spur New Saving

Research has shown that high-income households are much more likely than other households to save adequately for their retirement, even in the absence of tax incentives. The research indicates that high-income people would tend to use new pension tax breaks primarily as a way to shelter more income from taxation. They would primarily respond to these tax breaks not by increasing the total amount they save but by shifting existing savings from taxable accounts to tax-advantaged accounts. As a result, raising the IRA income limits or increasing the IRA or 401(k) contribution limits would likely do little to encourage new private saving.

These tax breaks would, however, increase the federal budget deficit, unless their high costs were offset on an ongoing basis. They thus would be likely to reduce national saving.

National saving is the sum of private saving and either public saving (government surpluses) or public dissaving (government deficits, which soak up private savings). If the amount by which a tax proposal increases the deficit exceeds the amount of new private saving the proposal induces, then the proposal reduces overall national saving. That would likely be the effect of proposals to eliminate the IRA income limit, raise IRA or 401(k) contribution limits, or create health IRAs, unless the cost of these tax breaks were offset on an ongoing basis (i.e., not just over the first ten years.) Lower national saving would likely have a negative impact on long-term economic growth.

Proposals Would Exacerbate Problems of Current Pension System

Existing tax incentives for pension saving are “upside down”: they are worth the most to people at very high income levels — who are the most likely to save on their own anyway — and worth the least to lower income individuals, who most need to save more for retirement.[9] Tax Policy Center analyses show that under current law, the top 20 percent of households receives 70 percent of the tax breaks associated with 401(k)s and IRAs. In contrast, the bottom 60 percent of households receives only 11 percent of these retirement tax subsidies. Moreover, nearly all — 95 percent — of those who did not contribute to retirement accounts in 1997 had incomes of less than $80,000.[10]

Raising contribution limits on 401(k)s or IRAs, or removing the income limit on IRAs, would make pension tax incentives even more lopsided, skewing tax subsidies for retirement saving even more heavily to those at the top of the income scale. Such proposals would do virtually nothing either to encourage ordinary workers who do not participate in a 401(k) plan or an IRA to save for their retirement or to provide incentives for low- and moderate-income workers to save more. Moreover, as noted above, some of these proposals would provide incentives to business owners to scale back employer contributions to a retirement plan or not to offer a plan in the first place, so the net effect on retirement saving by ordinary workers could even be negative.

Would Eliminating IRA Income Limits for High-Income Households Lead to More Retirement Savings by Non-affluent Households?

Some proponents of eliminating income limits on IRAs argue that doing so would lead financial services firms to advertise IRAs more aggressively, and that such advertising would, in turn, encourage moderate-income households to save more. Brookings Institution economists William Gale and Peter Orszag have found this claim to be without much foundation.

Gale and Orszag have noted that when such advertisements were used prior to 1986 — when there were no income limits on tax-deductible IRAs — much of the advertising was “designed to induce asset shifting among higher earners rather than new saving among lower earners.”* They have shown that some of the ads run in those years explicitly declared that people could make money by shifting $2,000 (then the maximum IRA contribution allowed) “from your right pants pocket to your left pants pocket,” with the left pocket being an IRA.

Gale and Orszag also observed that the higher levels of IRA contributions made between 1981 and 1986, the period when there were no income limits on tax-deductible IRAs, appear to have consisted largely of shifts of assets from taxable to tax-advantaged accounts. The Congressional Research Service found in a similar vein that, in the period from 1981-1986, “there was no overall increase in the savings rate...despite large contributions to IRAs.”

* Gale and Orszag, “An Unwise Deal.” The ad cited here ran in TheNew York Times.

Proposals Would Likely More than Offset Social Security Benefit Reductions for High-income Individuals But Not for Average Families

Under the sliding-scale reductions in Social Security benefits that President Bush has proposed, middle and high earners would face larger benefit reductions than low earners. In comments in late April, Chairman Thomas (and Social Security Subcommittee chairman Jim McCrery) suggested that the inclusion of pension-related tax breaks in Social Security legislation could compensate middle- and upper-income workers for their larger Social Security benefit reductions.

Proposals such as raising IRA and 401(k) contribution limits, eliminating IRA income limits, and creating health IRAs, however, would primarily benefit those at the top of the income spectrum while doing little or nothing to offset the benefit reductions in Social Security benefits that ordinary middle-income workers would face.

In recent testimony before the House Ways and Means Committee, Jason Furman (an economist at New York University and a senior fellow at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities) used two hypothetical families — the Smiths and the Jones — to illustrate the combined effects of expanded RSA-style tax incentives and the Social Security benefit reductions the President has proposed.[11]

- The Smiths make $400,000 annually and retire in 2055. Their annual Social Security benefit is cut by $13,085 a year (in today’s dollars) under the President’s sliding-scale benefit reductions (a reduction of 37 percent). The Smiths put $5,000 annually into a tax-free savings account that has no income limit, such as a RSA, that Social Security legislation has established. Previously, the Smiths would have saved this money in a taxable account because they were not eligible to use IRAs due to their high income. By the time they retire, the tax benefits from the tax-preferred account save the Smiths $250,000 (in 2005 dollars). That is enough to buy a $17,000 annuity, which more than makes up for their Social Security benefit reduction and leaves them ahead by $3,915 a year.

- The Joneses make $37,000 annually (the current average wage level). They also retire in 2055. Their annual Social Security benefit would be cut by $4,522 under the President’s proposal, a reduction of 21 percent. Unlike the Smiths, the Joneses are currently eligible to contribute to an IRA, and like most families today, they do not make enough to contribute the maximum amount allowed. They receive no benefit from changes to remove the IRA income limits or raise IRA contribution limits. As a result, they do not have any additional money to make up for the $4,522 reduction in their Social Security benefit, leaving them behind by $4,522 each year.

Steps To Improve Retirement Savings Should Target Those Most in Need

Most households nearing retirement have relatively low levels of savings. Using data from the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer of Finances, Brookings economist Peter Orszag estimates that the median value of assets in 401(k)s and IRAs for households nearing retirement (ages 55-59) was only about $10,000 in 2001.[12]

This problem is particularly acute for lower-income households. Households in the top 10 percent of the income spectrum hold more than half of all assets in 401(k)s and IRAs. Those in the bottom 40 percent of the income spectrum hold only about 5 percent of these assets.

There are a range of proposals that could help low- and middle-income families save more for retirement, such as making contributions to 401(k) plans more automatic, allowing workers to split tax refunds so they can deposit a portion of their refund into a retirement account, extending and improving the existing Saver’s Credit (which is slated to expire at the end of 2006), and exempting retirement accounts from the asset tests used in means-tested assistance programs.[13] These proposals would help raise the personal savings of families most in need and also would contribute to higher national savings, particularly if their costs were offset.

Proposals to raise income and contribution limits, on the other hand — or to create health-related tax shelters that feature both tax-deductible contributions and tax-free withdrawals — would move the retirement system in the wrong direction. Policymakers should not adopt such proposals. Moreover, they should resist attempts to couple the misguided and expensive proposals with more sensible reforms, as doing so would make the price of the desirable changes too high.

Proposals Could Cause Large Revenue Losses for States

Most of the additional tax benefits for retirement accounts and health care that the Ways and Means Committee may consider have implications for state revenues. Federal tax changes often affect state tax revenue because most states use federal definitions of income and other features of the federal tax code as the basis for their own taxation.

Retirement Savings Accounts

The Administration’s Retirement Savings Account proposal would replace IRAs with RSAs, which essentially are Roth IRAs without an income limit. There would be a revenue gain at the federal and state levels in the first few years, because individuals would move balances in their traditional IRAs into the new RSAs and pay taxes on those balances. (These taxes otherwise would have been paid when they withdrew the funds in retirement.) This would be followed by large revenue losses beginning a few years from now and growing every year thereafter for several decades.

All states with an income tax other than Massachusetts and Pennsylvania currently conform in most respects to the federal tax treatment of Roth IRAs (and Pennsylvania accords them treatment nearly parallel to the federal treatment). States are likely to feel substantial pressure to continue providing a tax break for savings. If RSAs are enacted, states are very likely to conform to the federal tax treatment of them, just as they currently conform to the federal tax treatment of IRAs.

The fact that the revenue losses would be postponed for several years could make conformity difficult to resist even for states, such as California and Virginia, that do not automatically conform to federal income tax changes. The enticement of a short-term revenue gain would combine with the advantages of uniform national treatment on this type of provision to increase the probability of conformity.

Raising Contribution Limits in Retirement Plans

Other proposals would increase the amount a taxpayer could deposit annually in various types of retirement plans such as 401(k)s and IRAs. Just as deposits to qualified retirement accounts are excluded from income for federal tax purposes, they also are excluded from income in all states except Pennsylvania. (New Jersey allows an exclusion for 401(k)s but not for other pension plan types.)

Health IRAs

Proposed health IRAs would allow a portion of funds from tax-deductible retirement savings plans such as 401(k)s and IRAs to be withdrawn tax-free after retirement to pay for out-of-pocket medical costs. These proposals pose still another threat to state revenues. States would lose large amounts of tax revenue at a time when they will be struggling to meet the rising costs of Medicaid for an aging population.

The Bond Market

In addition, all states — including those that do not levy income taxes — could experience increased costs as a result of these proposals. Tax-advantaged savings vehicles that can be used by high-income taxpayers provide such taxpayers with an alternative to purchasing tax-exempt bonds issued by states and localities. As new types of tax-free savings opportunities compete with tax-exempt bonds, it is likely that states and localities would have to offer higher interest rates to attract sufficient investment in their bonds.

Appendix: Income and Contribution Limits for IRAs and 401(k)s Under Current Law

This paper examines proposals related to Individual Retirement Accounts and employer-sponsored defined contribution plans, such as 401(k)s. There are currently two types of IRAs — a traditional IRA and a Roth IRA. Traditional IRAs and 401(k)s provide a tax deduction up-front at the time the contribution is made; withdrawals from the accounts during retirement are taxed as ordinary income. Roth IRAs are structured differently; contributions are not tax deductible, but withdrawals from Roth IRAs are tax free. (That is why Roth IRAs are often referred to as “backloaded;” the revenue losses associated with these accounts do not occur until many years in the future, when the funds are withdrawn.) Under both types of IRAs, as well as 401(k)s, assets in the accounts are allowed to grow from year to year without the earnings on the accounts being taxed.

Income Limits: Defined contribution plans such as 401(k)s are only available through an employer. Although employers may place restrictions on participation (such as a minimum number of years of employment), 401(k)s are available to earners at all income levels. IRAs are not linked to employers. But unlike 401(k)s, contributions to IRAs are available only to workers with incomes below certain levels.

- For traditional IRAs, a full tax deduction in 2005 is available to individuals covered by an employer pension plan with incomes below $50,000 (the deduction phases out completely at $60,000 of income). Married couples must have incomes below $70,000, with the deduction phasing out between $70,000 and $80,000 for couples. (The income limit for couples rises to $80,000 in 2007, with the deduction phasing out completely at $100,000.) Individuals and couples not covered by employer plans can make deductible contributions at any income level.

- For Roth IRAs, individuals can make the maximum allowable contribution if their income is below $95,000 and couples can do so if their income is below $150,000. Allowable contributions to Roth IRAs phase out between $95,000 and $110,000 for individuals and $150,000 and $160,000 for couples.

Contribution Limits: The 2001 tax-cut package substantially increased the contribution limits for both 401(k)s and IRAs. In 2001, the contribution limit for 401(k)s was $10,500 per worker. The 2001 tax-cut package increased the limit to $14,000 by 2005; the limit rises to $15,000 in 2006. For traditional and Roth IRAs, the contribution limit was increased to $4,000 by 2005, up from the previous maximum of $2,000, and will rise to $5,000 in 2008. Couples generally can contribute twice these amounts to IRAs regardless of whether a spouse works.

The contribution limits are higher for people aged 50 and over. Starting in 2008, the IRA contribution limit for such people will be $6,000 for individuals ($12,000 for couples), while the 401(k) contribution limit for those 50 and older will be $20,000.

After 2010, when all of the provisions in the 2001 package are slated to expire, the income and contribution limits are supposed to fall back to the levels dictated by the laws in place in 2001. Few observers believe that this will be permitted to occur. It is widely anticipated that the increases in contribution limits will be extended.

End Notes

[1] See Martin Vaughan, “Thomas Details Vision for Developing Broad Retirement Bill,” CongressDaily, May 13, 2005; Jonathan Weisman and Jeffrey H. Birnbaum, “Bush Ally in House Alters Social Security Debate Strategy,” Washington Post, May 5, 2005; and transcript of news conference in FDCH Political Transcripts, April 29, 2005.

[2] William Gale and Peter Orszag, “An Unwise Deal: Why Eliminating the Income Limit on Roth IRAs Is Too Steep a Price to Pay for a Refundable Savers Credit,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 4, 2004.

[3] Gale and Orszag, op. cit.

[4] Robert Carroll, “IRAs and the Tax Reform Act of 1997,” Office of Tax Analysis, Department of Treasury, January, 2000.

[5] Robert Carroll, op. cit.; David Joulfaian and David Richardson, “Who Takes Advantage of Tax-Deferred Savings Programs? Evidence from Federal Income Tax Data,” Office of Tax Analysis, Department of Treasury, 2001; Congressional Budget Office, “Utilization of Tax Incentives for Retirement Saving,” August 2003; General Accounting Office, “Private Pensions: Issues of Coverage and Increasing Contribution Limits for Defined Contribution Plans,” GAO-01-846, September 2001; and Craig Copeland, “IRA Assets and Characteristics of IRA Owners,” EBRI Notes, December 2002.

[6] Congressional Budget Office, “Utilization of Tax Incentives for Retirement Savings,” August 2003.

[7] Peter R. Orszag, “Improving Retirement Security,” Testimony before the House Ways and Means Committee, May 19, 2005.

[8] Jane G. Gravelle, Congressional Research Service, “Effects of LSAs/RSAs Proposal on the Economy and the Budget,” January 6, 2004.

[9] The tax benefits associated with tax-advantaged saving accounts are a function of an individual’s marginal income tax rate. A moderate-income individual in the 10 percent or 15 percent tax bracket, for instance, would receive a tax reduction of $10 to $15 for a $100 contribution to a retirement account. For a high-income individual facing the top 35 percent income tax rate, the same $100 contribution would reduce his or her taxes by $35. Low-income individuals who owe no income tax receive no tax benefit from these deductions.

[10] Peter Orszag, “Progressivity and Saving: Fixing the Nation’s Upside-Down Incentives for Saving,” Testimony before the House Committee on Education and Workforce, February 25, 2004.

[11] Jason Furman, “Evaluating Alternative Social Security Reforms,” Testimony Before the House Committee on Ways and Means, May 12, 2005.

[12] Orszag, “Progressivity and Saving.”

[13] These and other proposals are presented in detail by the Retirement Security Project; www.retirementsecurity.org.