- Home

- Nearly All Recent Section 8 Growth Resul...

Nearly All Recent Section 8 Growth Results From Rising Housing Costs and Congressional Decisions To Serve More Needy Families

Growth in Program Costs Set to Slow in Next Few Years

Administration officials have raised concerns that the Section 8 housing voucher program, the nation’s principal low-income housing assistance program, has grown excessively in recent years. They have said the Administration’s forthcoming budget will include proposals to reduce voucher costs. [1]

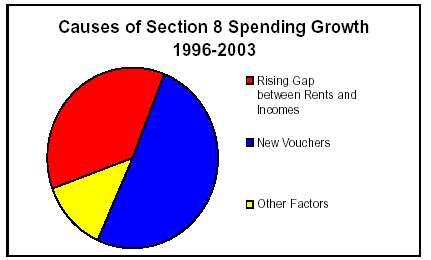

Analysis of total expenditures (or “outlays”) for the Section 8 program, which includes both the voucher program and a “project-based” housing assistance program, shows that the great majority of recent Section 8 spending growth has been due to two factors: (1) Congressional decisions to expand the program to serve more of the families eligible for it; and (2) a widening of the gap between housing costs and the incomes of low-income families, especially during the recent economic downturn. [2] The good news is that the Congressional Budget Office and other analysts expect the growth in voucher costs to slow markedly in the next few years, due primarily to the cooling of the housing market.

Reasons for Past Growth in Voucher Spending

Over the past eight years, from 1996 to 2003, Section 8 expenditures have risen at an average rate of approximately 4 percent per year. Of this increase:

-

Approximately 37 percent has resulted from a growing gap between housing costs and the incomes of low-income families. Private market rent and utility costs rose at an unusually rapid pace in recent years, while the earnings of low-income families grew more slowly and then declined during the recent economic downturn. For example, from 2000 to 2002, rent and utility costs rose by 8.5 percent, while the average income among the bottom fifth of households fell by 1.6 percent. Since vouchers typically cover the difference between the cost of a modest apartment and 30 percent of a family’s income, the government’s cost in providing a voucher rises when the gap widens between the rental charge and a family’s income.

The widening of this gap accounts for the great majority of the recent growth in the average cost of a voucher. In fact, growth in per-voucher costs due to other factors, such as policy changes and increases in administrative expenses, accounts for only about five percent of the recent increase in Section 8 costs. -

Approximately 51 percent of the growth in Section 8 expenditures stems from Congressional decisions to increase the number of families the voucher program assists. In recent years, Congress has expanded voucher program enrollment in two main ways. First, Congress has provided vouchers to families that are losing certain other types of federal housing subsidies — such as public housing and assistance under federal mortgage subsidy programs — as a consequence of Congressional decisions to allow those subsidies to end. These vouchers account for about one-third of the total increase in the number of Section 8 subsidies from 1996 to 2003. Because they took the place of existing subsidies, these vouchers did not result in a net increase in the number of families receiving housing assistance, and the growth in voucher costs that these vouchers have engendered is offset to some degree by a reduction in expenditures elsewhere in the budget.

Second, Congress created some new “incremental vouchers” between 1999 and 2002. These vouchers helped to reduce the number of eligible families unable to participate in the voucher program — and often stuck on long waiting lists — because of funding limitations. Only about one in every four low-income families eligible for vouchers receives any type of federal housing assistance.

- Some increases in costs in recent years have resulted from successful efforts to reduce the number of unused vouchers. The share of authorized vouchers that state and local housing agencies actually put to use rose from 90.5 of such vouchers in fiscal year 2001 to 96 percent midway through fiscal year 2003. [3] This increase reflects the success of efforts by HUD and state and local housing agencies to raise the proportion of authorized vouchers that actually are in use serving families. These efforts were undertaken after Congress expressed strong concerns that too many authorized vouchers were being left unused and were facilitated by a number of voucher program reforms that Congress encouraged or required and that HUD instituted.

Outlays Are the Appropriate Measure of Section 8 Cost Growth

The federal government measures budget trends in programs in two ways: by tracking changes in the amounts of new funding (or “budget authority”) that Congress appropriates for a program, and by tracking changes in the level of actual program expenditures (or “outlays”). For the Section 8 program, these two measures paint sharply different pictures of growth in recent years. From 1996 to 2003, budget authority for the program grew at an annual rate of 19 percent, while outlays grew at an annual rate of 4 percent.

The important figures here are those for outlays. This is true for two reasons. First, it is outlays — or actual government expenditures — that determine a program’s cost and its impact on budget deficits or surpluses. Second, the unusually large increases in budget authority for the Section 8 program are an artifact of a major change that was made in the Section 8 funding structure. Most Section 8 units were initially funded in the 1970s and 1980s through long-term contracts under which Congress provided up front all of the budget authority expected to be needed to support the units during the full term of the contracts, which usually was a period of several decades. Beginning in the mid-1990s, these long-term contracts started to expire, and Congress began providing new funding for these units on an annual, rather than a multi-year, basis. As a result, the amount of new budget authority needed to support the existing Section 8 units each year grew at a substantial clip. But this increase in budget authority did not reflect an increase in program costs or in the level of assistance provided.

Outlays for Section 8 units are recorded each year as they occur, regardless of whether the unit is under a long-term contract or a one-year contract. Outlay growth provides the only accurate measure of actual increases in Section 8 costs.

CBO Projects Voucher Cost Growth Will Slow Considerably

Each of the factors that have driven the recent growth in Section 8 costs is temporary and is likely to ease in coming years.

- Growth in market rents has slowed. In fiscal year 2003, residential rents nationally grew at the slowest rate in six years. The full effect of this cooling of the rental market was not immediately reflected in Section 8 costs because of the way in which subsidy levels are determined in the program. But the full effect will be felt — and will slow the growth of voucher costs — in coming years. The reason for the lag is that HUD makes adjustments each year in the limits on how much rent a voucher can cover (these limits are referred to as “Fair Market Rents,” or FMRs), using housing market data that in most cases are nine months old. In addition, after HUD adjusts an FMR, other administrative processes may result in it taking another year or more for the adjustment to be reflected widely in the rent-subsidy levels of individual families. As a result, the more rapid rent increases that occurred in 2001 and 2002 continue to influence voucher cost growth into fiscal year 2004, while the impact of the cooling of the housing market in 2003 will not be fully reflected in a slowdown in Section 8 cost growth until 2005.

- Earnings of low-income families are likely to increase as the economy recovers. Many families experience a temporary decline in income during a recession because a parent loses a job or has his or her work hours reduced. The substantial rise in unemployment since 2001 has directly increased Section 8 costs by making Section 8 rental subsidies larger, since the subsidies cover the gap between rents and 30 percent of household income, and household income has fallen as a result of the weakened job market. As the job market recovers and the availability of work increases, many families with vouchers will experience increases in income, which in turn will slow the growth of Section 8 costs.

- Congress has provided no incremental vouchers since fiscal year 2002. When Congress appropriates funds for additional vouchers, it takes some time for HUD to award the vouchers to state and local housing agencies and for the agencies to distribute the vouchers to families. New vouchers typically are not in use until the year after the year for which Congress approves them, and then, quite frequently, only for part of that year. As a result, the new vouchers approved in the fiscal year 2002 appropriations legislation did not result in increases in expenditures until fiscal year 2003, and it will take until fiscal year 2004 before the increases in costs will be felt for all 12 months of the year. Fiscal year 2004, however, also will be the first year since fiscal year 1999 in which no new incremental vouchers are put into use for the first time (although some new vouchers replacing existing federal housing subsidies will be put to use). And fiscal year 2005 will be the first year in some time in which virtually no costs for new incremental vouchers are incurred at any time during the year.

- Recent growth in the percentage of authorized vouchers in use cannot continue at the same pace. In late 2003 and early 2004, the percentage of vouchers in use may have risen modestly above the 96 percent level that it reached in mid-2003. But state and local housing agencies cannot receive funding for more that 100 percent of their vouchers. Furthermore, as a practical matter, there is virtually no chance that housing agencies on average will be able to put 100 percent of their vouchers in use. All of this means that it simply is not possible for the recent rate of increase in voucher utilization to continue.

For these various reasons, the Congressional Budget Office projects that growth in Section 8 spending will slow to 1.8 percent in fiscal year 2005. CBO also projects Section 8 expenditures will rise 5.5 percent in fiscal year 2004, which is well below the rates of increase in fiscal years 2002 and 2003.

The bipartisan, Congressionally-mandated Millennial Housing Commission described the voucher program as “flexible, cost-effective, and successful in its mission” in its 2001 report, while a 2002 study by the General Accounting Office found the program to be more cost-effective than other major federal housing programs. As this analysis of Section 8 spending growth in recent years indicates, most of the growth has been driven by a combination of rising housing costs and Congressional decisions to extend assistance to more low-income families, rather than by an erosion of program efficiency .

Careful steps to improve further the voucher program’s cost-effectiveness would be worthwhile, as they would for any government program. There is, however, no need for drastic cost-cutting measures that risk harming the program and the more than two million low-income households — most of them working families, elderly people, or people with disabilities — that it serves.

End Notes

[1] The New York Times reported that “housing officials” said the Administration was “alarmed at increases in the cost of vouchers” and the upcoming budget would “control the rising cost of housing vouchers for the poor.” Robert Pear, “Bush's Budget for 2005 Seeks to Rein in Domestic Costs,” New York Times, January 4, 2004, p. A1.

[2] We will release a more detailed description of the analysis shortly. The findings reported here are preliminary findings based on the best available data. If additional data are provided in the Administration’s fiscal year 2005 budget request, which will be released on February 2, 2004, we will make revisions accordingly.

[3] In the years prior to 2003, HUD provided some funds to state and local agencies for vouchers that were not put to use. These funds were counted as outlays, even though they were not actually spent on vouchers and were later recaptured by HUD. Consequently, only part of the increase of 5.5 percent or more in the share of voucher that were in use was reflected in increased outlays.