The President’s 2006 budget includes a proposal to establish new savings tax breaks. An identical proposal was included in the Administration’s budget last year. The proposal would establish tax-favored “Lifetime Savings Accounts” and replace existing Individual Retirement Accounts with “Retirement Savings Accounts.” Further, there appears to be growing interest in Congress for expanding tax-preferred savings opportunities, particularly along the lines of the Administration’s RSA proposal. For instance, Rep. Rob Portman (before he was named to be the U.S. Trade Representative) introduced legislation that would establish RSAs. House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Bill Thomas has indicated that retirement savings expansions similar to the RSA proposal could be considered as part of a Social Security reform package.

The Administration’s proposals to establish LSAs and RSAs are ill-advised for the following five reasons.

1. They would be extremely costly over time and would make the nation’s long-term fiscal problems significantly worse. An analysis of the Administration’s proposals conducted last year by the Urban Institute-Brookings Institution Tax Policy Center found that the proposals to establish LSAs and RSAs would grow sharply in cost over time and ultimately would cost the equivalent of more than $35 billion a year. The Tax Policy Center analysis stated: “The revenue losses explode just as the baby boomers start to retire and the budget situation turns really bleak.”[1]

The Tax Policy Center also found that over the next 75 years, the cost of the proposals would be equal to more than one-third of the long-term Social Security deficit. In other words, the long-term fiscal consequences of enacting the proposals would be equivalent to the consequences of enlarging the long-term Social Security shortfall (i.e., the shortfall over the next 75 years) by more than 33 percent.

A recent analysis by the Congressional Research Service of the proposals reached similar conclusions. It, too, found that the cost of the proposals would grow sharply over time and ultimately reach very high levels. CRS estimated that in the long term, when the revenue losses engendered by the proposal reach a steady state, the costs of the proposals could reach today’s equivalent of $300 billion to $500 billion over ten years. [2]

Despite this large long-term cost, the proposals are designed in a way that would produce savings in the first five years. They do this by using timing gimmicks to accelerate into the next five years billions of dollars of taxes that otherwise would be collected in subsequent years. The acceleration of revenues from the future to the present is done on terms damaging to the Treasury. The Tax Policy Center found that one of the key mechanisms the proposals use to accelerate these revenue collections “effectively represent[s] borrowing from the future on very unfavorable terms.” The Joint Committee on Taxation has estimated that while the President’s savings proposals will increase revenues by $14.6 billion over the first five years that they are in effect, they would lose significantly more over the following five years, for a net loss of $2.4 million over ten years. These revenue losses would then grow much larger over time.

Administration officials have touted their savings proposals as a major simplification of the tax code. In their analysis of the proposal, Leonard Burman of the Urban Institute and William Gale and Peter Orszag of Brookings — three of the co-directors of the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center — assess this claim as follows:

“…simplification does not require massive increases in contribution limits or the proliferation of additional tax-preferred savings vehicles. The most costly features of the new proposal have nothing to do with simplification and much to do with allowing high-income households to shelter much more wealth than under current law.”[3]

The proposals’ timing shifts are problematic in another way as well: there is risk that the short-term savings the proposals produce over the first five years will mislead policymakers and the public to think the proposals do not ultimately carry large costs. Moreover, the savings that the proposals would generate over the next five years could tempt policymakers to use those savings to “finance” other tax cuts that have significant costs both over the next five years and in years after that. That would enable policymakers to deliver more tax cuts while claiming they were still on track to meet near-term budget targets.

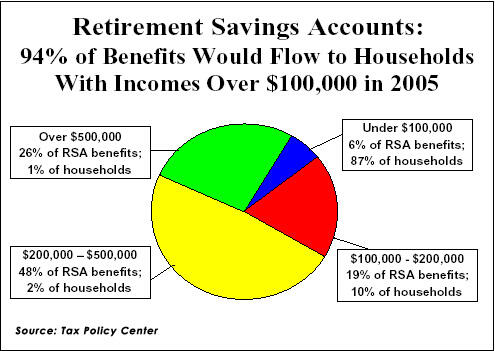

2. The benefits of the proposals would go overwhelmingly to high-income individuals. The Tax Policy Center’s analysis of the Administration’s proposals found that they “would be regressive on impact [that is, when implemented] and increasingly regressive over time.”[4] The benefits from the proposed Retirement Savings Accounts would be particularly skewed, with virtually all of the new tax benefits going to people with incomes over $100,000. If Retirement Savings Accounts were in effect in 2005, the Tax Policy Center found that 94 percent of the benefits would flow to the 13 percent of households with incomes over $100,000, and nearly three-quarters of the benefits would go to the 3 percent of households with incomes over $200,000. Since these individuals need the least incentive to save, compared to people with lower incomes, the proposal would contribute to the “upside-down” nature of the current system of tax incentives for saving (see box below ).

The proposals would have these effects for several reasons. First, the proposals would sharply increase the maximum amounts that can be deposited each year in tax-favored retirement and savings accounts. Yet the current contribution limits already exceed what all but affluent Americans can afford to set aside each year. Studies have found that only about five percent of those eligible to contribute to IRAs contribute the maximum amount, while only about five percent of 401(k) participants contribute the maximum amount allowed by law to 401(k)s. [5] The only people who would benefit directly from the Administration’s proposals to raise the contribution limits are those who already contribute the maximum amounts and can afford to contribute still more.

Second, the Administration proposals would eliminate all income limits on tax-favored contributions to retirement accounts. Under current law, the income limit on contributions to Roth IRAs is $160,000 for married filers. (The income limit is lower for tax-deductible contributions to traditional IRAs by individuals whose employer offers a pension plan; the income limit for making tax-deductible contributions to traditional IRAs is currently $80,000 for a married couple and is scheduled to rise to $100,000 by 2007.)

Under the Administration’s proposals, wealthy individuals thus would reap stunning windfalls. Each year a wealthy family of four would be able to transfer up to $30,000 in assets from taxable investment accounts to the new tax-free accounts. The family would be able to place $10,000 a year into its Retirement Savings Account and $20,000 a year into Lifetime Savings Accounts. [6] These amounts would be in addition to the $28,000 a year, rising to $30,000 by 2006, a family with two workers can already place in tax-favored 401(k) plans. [7]

Over time, wealthy families could shift hundreds of thousands of dollars into the tax-sheltered accounts, in which all earnings would forever be tax free. As the decades passed, a steadily increasing share of the income earned on the assets of wealthy American would escape taxation altogether. This is a key reason that the proposals are so expensive over time.

3. The proposals would do little to boost private saving and, as a result, would almost certainly reduce national saving and consequently have a negative long-term effect on economic growth. Sustaining a strong rate of economic growth entails having adequate national saving; saving provides the capital for new business investments. The level of national saving does not depend upon private saving alone; it is the sum of private saving (saving by private individuals and firms) and public saving (or government surpluses). Government deficits constitute negative saving — they result in private saving being soaked up to cover deficits rather than invested in the private sector.

For the Administration’s proposals to increase national saving, they must increase private saving by more than it reduces public saving — that is, by more than they enlarge the deficit. But the Tax Policy Center’s analysis of the Administration’s current proposals, as well as analyses of last year’s proposals and a substantial body of economic research, suggest such an outcome is implausible. The loss of public savings — that is, the increase in the deficit — would be substantial, as discussed above. But the anticipated increase in private savings is likely to be quite small.

- Economic research shows that when savings tax breaks are offered to high-income individuals — who would be the principal beneficiaries of the Administration’s proposals — these individuals tend to shift assets from existing investment-account vehicles into the tax-favored vehicles, rather than to undertake new saving.[8] The finding that savings tax breaks do little to increase saving among high-income individuals is a key reason why policymakers placed income limits on IRA tax breaks in the first place.

In commenting on a similar proposal in the late 1990s, then-Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin explained, “…if you don’t have income limits then you’re going to be creating a great deal of benefit for people who would have saved anyway, and all of that benefit will get you no or very little additional savings.”[9] Similarly, in its recent analysis of the savings proposal in the President’s fiscal year 2006 budget, the Congressional Budget Office concluded that high-income individuals who have savings in taxable accounts would shift funds from these accounts into the new tax-preferred accounts — an action that would have “no effect on the total amount of private saving.” [10] In addition, the CRS report referred to earlier points out that the last time IRAs were made available without any income limits, “There was no overall increase in the savings rate…despite large contributions to IRAs.” - Dampening any positive effects on private savings further, the proposals would weaken incentives for firms to offer pension plans for their workers, as is explained below. Saving by ordinary workers, especially for retirement, might actually decline as a result. The proposal also could induce workers to shift funds from retirement savings accounts into the new Lifetime Savings Accounts, from which funds could be withdrawn and spent much more quickly. That, too, could negatively affect savings.

In short, the effects of the proposals in boosting private saving would likely be modest, while the effects in decreasing public saving — as a consequence of the large increases in deficits —would be substantial. The likely net effect of the proposal consequently would be a reduction in national saving. As three of the co-directors of the Tax Policy Center wrote in their analysis of these Administration’s proposals, “there is unlikely to be much effect on private savings” and “if the cost of these proposals is financed by more federal borrowing, national savings will actually decline.”[11]

4. The proposals are likely to lead to a reduction in retirement savings for those most in need of such savings because they would undermine the incentives for employers to offer pension plans for their workers. Under current law, unless a firm offers a pension plan for its employees, the maximum amount that owners and executives of the firm can contribute to a tax-advantaged retirement account each year is $8,000 ($4,000 each for themselves and a spouse, a level that is scheduled to rise to $5,000 apiece by 2008). To put away larger amounts in tax-favored retirement plans, owners and executives must set up pension plans that cover their workers as well as themselves.

Under the Administration’s proposal, however, this would no longer be the case. Owners and executives would be able to put $20,000 a year for themselves and a spouse into tax-favored saving plans — plus an additional $5,000 a year for each child — without having to offer a pension plan for their employees.

The likely result would be that pension coverage for ordinary workers would decline over time. Commenting on the 2004 budget proposals, an array of pension experts found this to be the case, including scholars at the Brookings Institution, the Urban Institute, and the Employee Benefit Research Institute, as well as the Profit Sharing/401(k) Council of America (CPSA) and the Small Business Council of America. For example, Jack VanDerhei, who is associated with the Employee Benefit Research Institute, commented about the tax breaks last year’s LSA and RSA proposals would provide: “That’s probably enough for most small employers who could jettison doing anything for their employees and still get enough of a tax break.”

A recent Congressional Research Service analysis also warned of this effect, stating that “some employers, particularly small employers, might drop their plans given the benefits of private savings accounts.” [12] Data in an earlier CRS report showed that 11.5 million households receive pension coverage through a small employer (i.e., through a firm employing fewer than 100 workers).

Furthermore, by offering tax breaks for savings in accounts from which funds can be withdrawn for any purpose at any time (the “Lifetime Savings Accounts”), the proposal could induce many workers to contribute less to retirement accounts and to put their money in shorter-term savings accounts instead, another effect the Congressional Research Service analysis identified. CRS noted: “Since LSAs have no strings attached, individuals might find it more attractive to reduce their voluntary 401(k) or similar contributions not matched by employer contributions and put such money instead into LSAs. Because these plans could easily be tapped for non-retirement uses, the LSAs could actually reduce retirement savings.”

5. The proposals would harm state budgets. State income tax codes generally conform to the federal tax treatment of savings. As a result, if LSAs and RSAs were established at the federal level, many states would experience large revenue losses. Under the proposals in the Administration’s fiscal year 2006 budget, state revenue losses could ultimately reach $4 billion a year. These losses would be mounting in the same years that the baby boomers were retiring in growing numbers and state budgets were increasingly being squeezed by mounting costs for long-term care (which Medicare does not cover) and other health care costs associated with an aging population (which Medicaid helps to cover for elderly and disabled people with low incomes).

States also would be likely to experience increased borrowing costs. The new tax-free savings accounts would compete with tax-exempt state and local bonds, likely forcing state and local governments to pay higher interest rates to attract sufficient investment in their bonds.

Saver’s Credit Is Better Targeted

Retirement saving will become more important in future decades as the baby boomers begin to retire, especially if Social Security and Medicare ultimately are pared back. But tax incentives for retirement saving in the current system are “upside-down,” offering the most tax benefits to those who need the least encouragement to save. The Administration’s proposals to expand tax-free savings dramatically would exacerbate this problem.

- About two-thirds of the tax benefits from current tax preferences for 401(k)s and IRAs go to the top 20 percent of households, according to the Tax Policy Center. This is both because those with higher incomes have a higher propensity to save than those with lower incomes and because the tax incentives to place money in retirement accounts are much greater for those in higher tax brackets.

- Studies suggest, however, that upper-income households are more likely than other households to shift existing savings in response to tax incentives — in order to shelter their wealth from taxation — rather than to save more. As a result, there is little evidence that current tax incentives are increasing saving.

- Indeed, an analysis by the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center* shows that the tax breaks the federal government provided in 2003 to promote saving cost nearly $50 billion more than the total amount that was saved by Americans in that year. The analysis found that, in general, while tax incentives for saving have been increasing since the early 1990s, personal saving has remained on a downward trend.

In contrast to the Administration’s LSA and RSA proposals, a provision in the 2001 tax-cut package — known as the “saver’s credit” — is aimed at encouraging savings among low- and moderate-income workers. This provision, which is available to singles with income up to $25,000 and married couples with incomes up to $50,000, is much better targeted on the segment of the population that receives the least benefit from current tax incentives and is most in need of additional savings to improve its economic security. Further, research indicates that this group, because it has far fewer assets than higher-income taxpayers, is more likely to respond to the incentive by increasing savings rather than simply shifting assets. Finally, the saver’s credit complements other saving vehicles, such as 401(k) and IRAs, as the credit is in addition to any of the incentives associated with these plans.

Despite the advantages the saver’s credit offers to reduce modestly the “upside down” nature of the current tax incentives for savings, the Administration has not called for extending this provision, which expires at the end of 2006. Some in Congress have called not only for extending the credit, but also for expanding it. Currently, the saver’s credit has a significant limitation that reduces its effectiveness in promoting saving: it does not apply to workers who do not earn enough to owe income taxes, although they may owe payroll and other taxes. Making the credit “refundable” so that these workers could qualify for it would extend this important savings incentive to low-income families.

*Elizabeth Bell, Adam Carasso, and C. Eugene Steuerle, “Retirement Savings Incentives and Personal Saving,” Tax Policy Center, Tax Facts, December 20, 2004.