- Home

- The Food Stamp Program Is Effective And ...

The Food Stamp Program is Effective and Efficient

Some in Congress have suggested that the Food Stamp Program can be cut this year by targeting “waste, fraud, and abuse.” In fact,

- The Food Stamp Program is efficient and effective. Program integrity has improved dramatically in recent years and food stamp error rates are now at an all-time low. USDA data show that over 98 percent of food stamp benefits go to eligible households. The low error rate is a major accomplishment for a large benefit program that is administered by thousands of eligibility workers in state and local offices across the country.

- As the U. S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) reported in May 2005, “[t]he payment error rate has fallen each year since 1999 … This decline in the payment error rate has been widespread: the rate fell in 42 states and the District of Columbia, and the rates in 18 of these states fell by at least one-third.”

- GAO further reported that “[a]lmost two-thirds of the payment errors in the Food Stamp Program are caused by caseworkers, usually when they fail to act on new information or make mistakes when applying program rules.” In addition, the program’s success in serving the working poor contributes in part to its error rate: according to GAO, “managing cases with earnings contributes to payment error in part because caseworkers may find it difficult to keep up with frequent changes reported to them.”

- Any policies that would significantly reduce food stamp benefit expenditures would have either to eliminate eligibility for various groups of low-income families and individuals or to reduce the already modest benefit amounts. Either approach would cause harm to the low-income households — such as families with children, the elderly, or people with disabilities — who depend upon the Food Stamp Program to help them afford an adequate diet.

- The Food Stamp Program’s benefits are already lean. Food stamp benefits average only about $1 per person per meal.

The Food Stamp Error Rate has Reached All-time Lows

- Almost ninety-nine percent of food stamp benefits are issued to eligible persons, the vast bulk of whom are children and parents in low-income families, senior citizens, and people with disabilities.

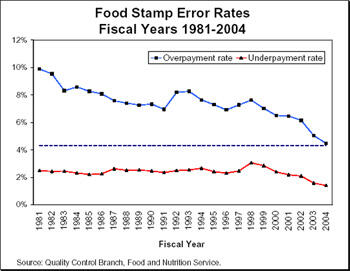

- On June 24, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) announced that the national combined payment error rate in 2004 reached is sixth consecutive all-time low at just 5.88 percent. Until recently 6 percent was the threshold the Food Stamp Act established for exemplary performance. An error rate below 6 percent qualified a state for a bonus payment or enhanced funding. Now, because of improved payment accuracy, the national average has exceeded this exemplary level.

- Some portray the food stamp “combined” error rate as a reflection of the dimension of excessive federal expenditures due to errors. This is incorrect since the combined error rate includes underpayments that save the Program money. The USDA issues three separate payment error rates: the overpayment error rate, the underpayment error rate, and the combined payment error rate. The overpayment error rate counts benefits issued to ineligible households as well as benefits issued to eligible households in excess of what federal rules provide. The underpayment error rate measures errors in which eligible, participating households received fewer benefits than the Program’s rules direct. The combined payment error rate is the result of summing (rather than netting) the overpayment and underpayment error rates. As GAO notes, “[u]nderpayments represent unintentional financial savings to the federal government.”

In other words, to calculate the combined payment error rate USDA adds together the overpayment error rate, which in 2004 was 4.48 percent nationally, and the underpayment error rate, which in 2004 was 1.41 percent, to reach a combined error rate of 5.88 percent. The net loss to the federal government, however, from the errors in that state’s program (i.e., the benefits lost through overpayments minus those saved by underpayments) would be only three percent.

Image

- Finally, since 98 percent of benefits go to eligible households, about half of overpayments result from eligible low-income households getting benefits that are modestly in error, rather than from ineligible households participating.

- Relatively few of these errors represent dishonesty or fraud on the part of recipeents (for example, recipients lying to eligibility workers to get more food stamps). The overwhelming majority of food stamp errors result from honest mistakes by recipients, eligibility workers, data entry clerks, or computer programmers. In recent years, states have reported that about half of the dollar value of overpayments and three-quarters of the dollar value of underpayments were their fault, rather than recipients’ fault. Much of the rest of overpayments resulted from innocent errors by households facing a program with complex rules.

- GAO reports that USDA and the states “have taken many approaches to increaseing food stamp payment accuracy, … includ[ing] practices to improve accountability, perform risk assessments, implement changes based on such assessments, and monitor program performance.” It found that these practices were “recognized as being effective in reducing payment errors.”

- It also should be recognized that overpayments are counted in a state’s error rate even when the overpaid benefits are recouped from households. In fiscal year 2002, states collected over $200 million in overissued benefits. New collection techniques, such as intercepting wage earners’ income tax refunds, are expected to increase collections further.

- Food stamps now come in the form of an electronic debit card –– like the ATM cards that most Americans carry in their wallets. The food stamp debit cards are used in the supermarket checkout line only to purchase food. This has been a key tool to reduce food stamp fraud.

- Retailers or clients who defraud the Food Stamp Program by trading food stamps for money or misrepresenting their circumstances face tough criminal penalties. Sophisticated computer programs monitor food stamp transactions for patterns that may suggest abuse. Federal and state law enforcement agencies are then alerted and investigate.

- Food stamp error rates compare favorably to those in other government programs for which data is available. For example, the Internal Revenue Service estimates a noncompliance rate with federal personal income taxes of at least fifteen percent in 2001. This represents at least $257 billion lost to the federal government.[1]

Savings Could Come Only From Harmful Benefit Cuts

- The Congress, the Administration, and states already have enacted and are carrying out measures to safeguard the Food Stamp Program from waste, fraud, and abuse. The 2002 Farm Bill, which reauthorized the Food Stamp Program for five years, contained major reforms to the food stamp quality control system. These reforms have contributed to the declines in the error rate in recent years.

- No one has proposed additional legislation that would curtail fraud in the Food Stamp Program without causing harm to low-income households. As discussed above, most of the errors result from honest mistakes that states or households make. If there were a magical policy to reduce fraud, Congress would already have enacted it.

- Any proposal that would extract large savings from the Food Stamp Program as part of this year’s budget would require cutting eligibility for food stamp benefits or lowering the already modest benefit levels. Such cuts would result in increased struggles for low-income families, the elderly, and people with disabilities to pay their bills and have enough money for the nutritious food they need.

Food Stamps are not Overly Generous

- Food stamp benefits are based on the amount that USDA has determined is minimally necessary for households to purchase a nutritiously adequate diet. The average food stamp benefit is only about $1 per person per meal.

- The Food Stamp Program is efficiently targeted to reach the people that have the most difficulty affording an adequate diet: over 95 percent of food stamp benefits go to households with income below the federal poverty level. About 80 percent of benefits go to families with children. Virtually all of the remainder goes to the elderly and people with disabilities.

- The last time the Agriculture Committees faced reconciliation instructions, in 1995 and 1996, the Food Stamp Program was cut by almost $28 billion over six years — almost 20 percent by the sixth year — as part of the 1996 welfare law. A substantial portion of these cuts came from across-the-board benefit reductions that affected nearly all recipient households, including families with children, the working poor, the elderly, and people with disabilities. In addition, eligibility was severely curtailed for legal immigrants and unemployed childless adults. Since 1996, Congress has enacted several pieces of legislation that have undone or moderated some of the most severe cuts, but about two-thirds of the cuts remain in effect.

- Although the Budget Committees sought to justify the 1995-1996 reconciliation instructions as attacks on waste, fraud, and abuse and toughening work and other behavioral requirements, a total of only three percent of the savings the Agriculture Committees found came from anti-fraud provisions, stronger sanctions on people refusing to work, and reduced administrative costs. Some 97 percent of the savings came from eligibility and benefit cuts.

- After unemployment insurance, the Food Stamp Program is the federal benefit program that is most responsive to the economy. Food stamp participation and spending have grown since 2000, primarily because of the economic slowdown that turned into a recession in 2001. But it is important to remember that this growth followed 6 years of declining participation and spending that occurred primarily because of the strong economy of the late 1990s.

The net result is that over the past ten years, food stamp spending has grown at an average annual rate about the same as the rate of inflation. Between 1995 and 2005, food stamp spending grew at an average annual rate of 2.6 percent. Over that same period the rate of food price inflation (as measured by the Consumer Price Index) was 2.6 percent. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) currently forecasts that over the next 10 years, from 2005 to 2015, the average annual growth rate in food stamp costs will be only about 2 percent a year, very close to the projected rate of food price inflation. - The Food Stamp Program has not contributed significantly to the return to deficit spending. Between 2000 and 2005, increases in food stamp spending accounted for less than 1 percent of the swing from surpluses to deficits that occurred over those years. [2]

Topics:

End Notes

End Notes::

[1] Internal Revenue Service, New IRS Study Provides Preliminary Tax Gap Estimate (IR-2005-38, March 29, 2005), available at: http://www.irs.gov/newsroom/article/0,,id=137247,00.html .

[2] This calculation compares the change in food stamp spending over the 2000 to 2005 period as a share of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) to the change in the surplus/deficits as a share of GDP over the same period. See https://www.cbpp.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/2-4-05bud.pdf.

More from the Authors

Areas of Expertise

Stay up to date

Receive the latest news and reports from the Center