Statement by Chad Stone, Chief Economist, on the February Employment Report

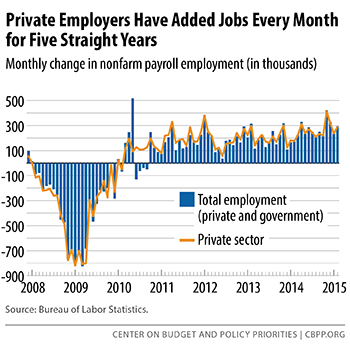

Today’s solid jobs report shows that private employers have added jobs every month for five straight years. Unemployment has dropped sharply, though it has room to fall further. To herald a truly healthy labor market, however, labor force participation should be higher — it fell in February as more people stopped looking for work than found jobs — which will mean a larger share of Americans should have a job; fewer people should be working part time because they can’t find full-time work; fewer people should experience long spells of unemployment before finding work; and wages should be rising faster.

At 5.5 percent, the unemployment rate is still 0.5 percentage points higher than at the December 2007 start of the recession. No one knows for sure how low the unemployment rate can go without triggering inflation concerns among Federal Reserve monetary policymakers, but both they and the Congressional Budget Office believe there is still room for a further decline.

The official unemployment rate does not include people who want a job — and in many cases would likely have one in a stronger labor market — but have not looked recently enough to be considered in the labor force and officially unemployed. Labor force participation fell sharply in the recession but then continued to fall through 2013, before stabilizing in the past year. Falling labor force participation offset the drop in unemployment and kept the share of the population with a job from rising as the economy improved. Participation edged down in February, taking back some of the large rise in January.

The potential labor force participation rate has likely fallen since the start of the recession as the leading edge of the baby boom generation has begun to retire. Most analysts, however, believe that stronger demand for goods and services would not only reduce unemployment — including long-term unemployment (27 weeks or longer) — but also raise labor force participation. It should also reduce underemployment of people who are now working fewer hours than they would like.

Finally, stronger demand should put more pressure on employers to raise wages. Private-sector average hourly earnings before adjusting for inflation have grown at a fairly steady 2 percent per year for the past five years (and showed little change in February). Consumer price inflation has been much more volatile over that same period but, on average, has grown only a couple of tenths of a percent a year more slowly, meaning real wages have risen very little over the period. With many more jobseekers than jobs, employers have faced little pressure to raise wages.

Job creation is proceeding at a good pace and unemployment and underemployment are falling, but wage growth has been anemic and far from what would indicate an overheating economy. That means the Federal Reserve should stay patient and let the labor market continue to heal before starting to raise interest rates.

About the February Jobs Report

Employers reported strong payroll job growth in February. In the separate household survey, the unemployment rate fell to 5.5 percent, but labor force participation declined as well.

- Private and government payrolls combined rose by 295,000 jobs in February, while job growth in January was revised down by 18,000 (to 239,000). Private employers added 288,000 jobs in February, while overall government employment rose by 7,000. Federal government employment was unchanged, state government rose by 3,000, and local government by 4,000.

- This is the 60th straight month of private-sector job creation, with payrolls growing by 12.0 million jobs (a pace of 201,000 jobs a month) since February 2010; total nonfarm employment (private plus government jobs) has grown by 11.5 million jobs over the same period, or 191,000 a month. Total government jobs fell by 565,000 over this period, dominated by a loss of 359,000 local government jobs.

- The job losses incurred in the Great Recession have been erased. There are now 3.2 million more jobs on private payrolls and 2.8 million more jobs on total payrolls than at the start of the recession in December 2007. Because the working-age population has grown since then, the number of jobs remains well short of what is needed to restore full employment. But growth like that of the last three months (an average monthly gain of 288,000 jobs) bodes well for closing that gap.

- Average hourly earnings on private nonfarm payrolls rose by 3 cents in February to $24.78. Over the last 12 months they have risen by 2.0 percent. For production and non-supervisory workers, average hourly earnings were unchanged at $20.80 and only 1.6 percent higher than a year earlier.

- The unemployment rate dropped to 5.5 percent in February, and 8.7 million people were unemployed. The unemployment rate was 4.7 percent for whites (0.3 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession), 10.4 percent for African Americans (1.4 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession), and 6.6 percent for Hispanics or Latinos (0.3 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession).

- The recession drove many people out of the labor force, and the ongoing lack of job opportunities kept many potential jobseekers on the sidelines and not counted in the official unemployment rate. That pattern is evident in the today’s data. While the number of unemployed shrank by 274,000 in February, the number of people with a job rose by only 96,000. In other words, on net, a large share of the drop in unemployment showed up in a decline in the labor force of 178,000 rather than in employment. That’s a step backwards from the strong growth in labor force participation and employment in January. (The data on household employment and unemployment come from a different survey than those on payroll employment and show considerably more month-to-month variability.)

- The labor force participation rate (the share of the population aged 16 and over in the labor force) edged down to 62.8 percent in February, just shy of the 63.0 percent a year earlier. The sharp decline in labor force participation during much of the recovery appears over, but prior to recent years, the labor force participation rate hasn’t been this low since the 1970s and growth in participation will be needed to restore normal labor market health.

- The share of the population with a job, which plummeted in the recession from 62.7 percent in December 2007 to levels last seen in the mid-1980s and has remained below 60 percent since early 2009, remained at 59.3 percent in February. It was 58.8 percent a year ago.

- The Labor Department’s most comprehensive alternative unemployment rate measure — which includes people who want to work but are discouraged from looking (those marginally attached to the labor force) and people working part time because they can’t find full-time jobs — fell to 11.0 percent in February. That’s well down from its all-time high of 17.1 percent in April 2010 (in data that go back to 1994) but still 2.2 percentage points higher than at the start of the recession. By that measure, about 17.5 million people are unemployed or underemployed. The rate was 12.6 percent a year ago (about 20 million people).

- Long-term unemployment remains a significant concern. More than three in ten (31.1 percent) of the 8.7 million people who are unemployed — 2.7 million people — have been looking for work for 27 weeks or longer. These long-term unemployed represent 1.7 percent of the labor force. These figures were 36.8 percent and 2.4 percent a year ago. Before this recession, the previous highs for these statistics over the past six decades were 26.0 percent and 2.6 percent, respectively, in June 1983, early in the recovery from the 1981-82 recession. A year after peaking at 2.6 percent, however, the long-term unemployment rate had dropped to 1.4 percent, compared with the current rate of 1.7 percent more than five and a half years after the end of the recession.

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities is a nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization and policy institute that conducts research and analysis on a range of government policies and programs. It is supported primarily by foundation grants.