A call by several members of the President’s Commission on Fiscal Responsibility and Reform for the commission to focus on the federal government’s gross debt, rather than debt held by the public, is misguided and could inhibit efforts to address the nation’s long-term fiscal challenges.

Debt held by the public consists of promises to repay individuals and institutions, at home and abroad, who have loaned the federal government money to finance deficits. Gross debt (as the term is used in the United States) includes, along with debt held by the public, intragovernmental debt — money that one part of the federal government owes to another — such as the money the Social Security Trust Funds have lent to the Treasury in years when their earmarked revenues exceeded their expenditures for benefits and other costs.

The interest of some commissioners in gross debt stems at least partly from an analysis of 44 countries that, they believe, suggests that high levels of gross debt inhibit economic growth. In a widely cited article, University of Maryland professor Carmen M. Reinhart — who testified to the commission on May 26 — and Harvard professor Kenneth Rogoff concluded that debt-to-GDP ratios of 90 percent or more are associated with significantly slower economic growth. Since they use gross debt as the measure of debt for the United States, and since our gross debt now equals 90 percent of GDP, the nation appears close to that “tipping point.”

But claims that gross debt (as the term is used in the United States) is an economically meaningful measure of national debt and that the United States is approaching an economic danger zone are extremely dubious for several key reasons:

- Most economists agree that debt held by the public — rather than gross debt — is the proper measure on which to focus because that’s what really affects the economy.

- Reinhart and Rogoff used a measure of debt that, for most of the 44 countries they researched, is consistent with the standard measure of national debt that the International Monetary Fund and the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development use. Although those institutions call that measure “gross debt,” it is very different from what is called gross debt in the United States because it excludes most intragovernmental debt. The Reinhart-Rogoff data for the United States and Canada, however, differ significantly from the IMF and OECD measures because these Reinhart-Rogoff data reflect gross debt as that term is commonly used here — and thus include large amounts of intragovernmental debt, such as the money that the Social Security Trust Funds have lent to the Treasury.

This leads to two conclusions.

- First, since the gross debt measure that Reinhart and Rogoff use for countries other than the United States and Canada does not include significant amounts of intragovernmental debt, the Reinhart-Rogoff data do not allow them to reach valid conclusions about the effects of intragovernmental debt on economic growth.

- Second — and of particular note — the authors’ gross debt measure for countries other than the United States and Canada is roughly equivalent to what, in the United States, is called debt held by the public. In both cases, the measures essentially exclude intragovernmental debt. And by this measure, the U.S. debt-to-GDP ratio equaled 53 percent at the end of fiscal 2009 and, under current policies, will not reach 90 percent until around 2020.

Finally, while the authors argue that debt-to-GDP ratios over 90 percent are correlated with lower economic growth, they do not argue that the former causes the latter. In fact, other experts argue that lower economic growth may cause higher debt-to-GDP ratios, rather than the other way around.

To be sure, the specter of rising debt for decades to come presents a very serious economic challenge for our nation. But, in addressing this issue, the commission should focus on the right fiscal target — debt held by the public — rather than on a measure or target that will cause confusion and misunderstanding and does not make sound economic sense.

The United States faces a serious long-term fiscal problem. Large current deficits, which are the unavoidable result of the deep recession and necessary efforts to shore up the financial system and pull the country out of the downturn, are not the problem. But future deficits are projected to spiral out of control, eventually reaching unsustainable levels. Unless changes are made in current policies, deficits and debt will grow in coming decades to levels that most economists agree will have significant negative effects on the economy.

To deal with this challenge in a sensible way, it is important to focus on the true nature of the problem and how to measure it.

Most economists agree that the debt held by the public is what really affects the economy. As the Congressional Budget Office stated in its June 2009 report on the long-term budget outlook, “Long-term projections of federal debt held by the public, measured relative to the size of the economy, provide useful yardsticks for assessing the sustainability of fiscal policies.” In contrast, “gross debt . . . is not useful for assessing how the Treasury’s operations affect the economy.” [1]

A number of organizations and individuals concerned about the effect of rising deficits and debt on the budget and the economy — the Congressional Budget Office, the Government Accountability Office, the Committee on the Fiscal Future of the United States of the National Research Council and the National Academy of Public Administration, the Peterson-Pew Commission on Budget Reform, fiscal experts Alan Auerbach and William Gale, as well as the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities — have produced detailed assessments of the long-term fiscal problem facing the United States. [2] Every one of those studies focuses on debt held by the public. Every one concludes that federal debt will grow under current policies to levels that will be harmful to the economy. The decision to focus those studies on debt held by the public clearly does not arise from an effort by the authors to minimize the long-term problem the nation faces.

Debt held by the public is important because it reflects the extent to which the government goes into private credit markets to borrow. Such borrowing draws on private national saving and international saving and therefore competes with investment in the nongovernmental sector (for factories and equipment, research and development, housing, and so forth). Large increases in such borrowing can also push up interest rates and increase the future interest payments the federal government must make to foreign lenders, which reduces Americans’ income. By contrast, intragovernmental debt (the other component of the gross debt) has no such effects because it is simply money the federal government owes (and pays interest on) to itself.

Two examples clearly show that changes in the level of gross debt do not provide a reliable indicator of the real fiscal impact of the policies that produce those changes.

Budget analysts agree that reductions in scheduled Social Security benefits or increases in Social Security taxes would improve the federal government’s long-term fiscal outlook. But such reductions would not reduce the projected gross debt. Debt held by the public would decline because total deficits would be lower, but the reduction in Social Security benefits or increases in Social Security taxes would also increase the surplus of Social Security income over Social Security benefit payments. That would mean that the debt holdings of the Social Security Trust Funds (intragovernmental debt) would increase by an amount equal to the reduction in borrowing from the public. Gross debt would remain unchanged despite the clear improvement in the fiscal outlook.

| Significance of Debt Held by Social Insurance Trust Funds Although debt held by the public is the relevant concept for economic analysis, debt held by social insurance trust funds, such as Social Security, is important for budgetary purposes. When payroll taxes and other income of the trust fund exceed the amount needed to pay benefits and administrative expenses (as has been the case for Social Security since 1984), the surplus is credited to the trust fund and invested in special Treasury securities.a The balances in the trust fund provide legal authority to pay Social Security benefits when the Social Security program’s current income is insufficient by itself. If the trust fund becomes exhausted, benefit payments must be reduced to the level that incoming tax revenues can support. According to the latest projections of the Social Security trustees, this would occur in 2037 unless policymakers take corrective action.b Debt held by the public represents money that must be borrowed and periodically refinanced in private credit markets; interest payments on that debt represent a current drain on government resources. If the specter of excessive debt led investors to lose confidence in U.S. government securities, federal interest costs could increase substantially, with potentially troubling implications for U.S. and world economies. Debt held by social insurance trust funds, however, has no such economic significance. Since it does not need to be financed in credit markets, it cannot lead to a refinancing crisis. As legal authority to spend money in the future, it is essentially similar to legal authority to meet spending commitments for other entitlement programs that are not financed through trust funds and are not included in measures of federal debt. In addition, an increase in trust fund balances that provides authority for higher expenditures in some distant year is not at all equivalent to issuing more publicly held debt to finance additional spending today. If additional spending authority leads to more federal borrowing at some time in the future, that borrowing will add to debt held by the public when that spending occurs. _________________ a These securities, known as the Government Accounts Series, carry a market interest rate but are distinct from the marketable bills, notes, and bonds sold to the public to raise cash. bThe 2009 Annual Report of the Board of Trustees of the Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and Federal Disability Insurance Trust Funds, May 2009. |

Conversely, there is agreement that simple accounting changes in trust funds — for instance, transfers from the general fund to a trust fund when there are no new revenues to fund such a transfer — do not affect the real fiscal outlook. To take an extreme example, simply eliminating all trust funds without changing promised benefits for the associated programs would not improve the long-term fiscal outlook at all. Yet doing so would dramatically reduce gross debt. If we passed a

law today doing away with all trust funds, the gross debt would suddenly fall from 90 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) to 59 percent of GDP, but we would be facing precisely the same dire long-term fiscal problem. (See box.) This example also illustrates the problem of comparing the so-called gross debt of the United States with the gross debt of other countries that finance their social insurance programs on a pure pay-as-you-go basis. Our fiscal situation is not worse than theirs just because we use a trust-fund system to account for those programs and they do not.

Reinhart and Rogoff Overstate U.S. Debt Relative to That of Other Countries

In a widely cited article, Dr. Reinhart and her co-author, Kenneth Rogoff, conclude that debt-to-GDP ratios of 90 percent and up are associated with much slower real economic growth.[3] They specifically state that they are referring to central (or federal) government gross debt. Since U.S. gross debt, by their measure, equaled 90 percent of GDP in June 2010, the United States appears to be at that “tipping point.” A careful examination of Reinhart and Rogoff’s analysis, however, shows that this conclusion is not warranted.

Most international comparisons of debt use data compiled by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) or the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). What the IMF and OECD call gross debt represents a broad category of financial liabilities. It includes both credit market instruments — like U.S. Treasury securities — that central governments issue to raise cash and various other financial liabilities of government. It does not include securities issued by the central government to universal social-insurance systems like Social Security and Medicare. [4]

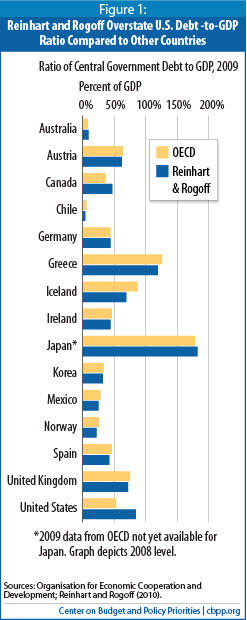

Reinhart and Rogoff did not use IMF or OECD figures, however, but collected data from various national statistical offices and other sources.[5] In the case of the U.S., that led them to include the debt held by social insurance funds. [6] For most countries, their choice of data made little or no difference to the debt numbers, since the resulting figures closely resemble the standard IMF or OECD measures. But for two countries — the United States and Canada — this is decidedly not the case (see Figure 1).[7]

This leads to two important observations about Reinhart and Rogoff’s figures. First, since the countries other than the United States and Canada that are included in their study do not include significant amounts of intragovernmental debt in their gross debt, the Reinhart and Rogoff data do not allow them to reach any valid conclusions about the possible effects of intragovernmental debt on economic growth. (By intragovernmental debt, we mean the debt that one part of a government owes to another part of the same government, rather than debt owed to outside creditors.)

Second, the gross debt measure that they use is, for countries other than the United States and Canada, roughly equivalent to debt held by the public, as we use the term in the United States. Accordingly, the 90-percent-of-GDP threshold that Reinhart and Rogoff posit should be viewed, with regard to the United States, as applying to the debt held by the public. By that measure, the ratio of U.S. central government debt to GDP stood at 53 percent at the end of fiscal year 2009. If current policies remain unchanged, it will reach 90 percent around 2020. [8]

Reinhart and Rogoff’s “Danger Zone” Is Misunderstood

But does the 90-percent debt-to-GDP level constitute a danger zone? While rising levels of U.S. federal government debt pose serious dangers over the long term, there are two reasons why it would be mistaken to conclude that the United States would pass into dangerous territory as soon as debt held by the public exceeded 90 percent of GDP.

First, Reinhart and Rogoff do not themselves assert that the 90-percent level represents some kind of tipping point. They simply have analyzed the relationship between debt and economic growth by grouping two centuries’ worth of data into four categories: years when central government debt-to-GDP levels were below 30 percent, between 30 and 60 percent, 60 to 90 percent, and over 90 percent. They found that economic growth was generally lower in the last group — that is, that there is a correlation over stretches of time between lower economic growth and debt-to-GDP ratios in excess of 90 percent. They did not find that growth begins to decline as soon as debt rises above 90 percent of GDP.

Second, Reinhart and Rogoff are careful not to imply that debt in excess of 90 percent of GDP caused slower economic growth. As economists know, correlation and causation are not the same thing. In this case, the question is: does economic growth sputter because of high debt, or does weak growth hammer government budgets and cause debt to rise? Paul Krugman, a Nobel laureate in economics as well as a prominent columnist, has written lucidly about this issue.

As Krugman observes, the Japanese and European experiences suggest that weak economic growth causes swelling debt, rather than the other way around. He notes that in Japan, “debt rose after growth slowed sharply in the 1990s. And European debt levels didn’t get high until after Eurosclerosis set in.”[9] Krugman adds that “Reinhart and Rogoff have not, as far as I can tell, made any effort to disentangle the causation here.”[10]

Krugman also points to the one experience with such a high debt-to-GDP ratio in the United States — in 1945-1947, when debt held by the public peaked at 109 percent of GDP. To be sure, the nation did suffer a short, sharp recession after World War II. But as Krugman explains, that occurred as the nation demobilized from the war and millions of women left the labor force; there is no evidence that the high debt levels, a legacy of the nation’s huge war costs, caused the downturn. And, in fact, the U.S. debt-to-GDP ratio fell rapidly after 1947 — from 96 percent to 49 percent over the next ten years — not because the debt fell, but because GDP surged.

In sum, Krugman laments: “The idea that Really Bad Things happen when debt crosses 90 percent of GDP is being treated as a solid fact, when it’s nothing of the sort.”[11]

Does this mean we should be unconcerned about our rising debt? Not at all. Investors view U.S. Treasury securities as a safe haven so long as they’re satisfied that the nation can continue to service its debt. A somewhat higher debt is tolerable; an exploding debt is not. That’s why CBO and others call policies that lead to ever-rising debt-to-GDP ratios and spiraling interest costs “unsustainable.”

The exact consequences of a relentlessly rising debt are hard to predict. A crisis in confidence could occur. More insidiously, a growing debt-service burden will hamper domestic investment by soaking up too much capital (or, if financed by foreign lenders, will funnel profits from such investments overseas). Some analysts believe that we would eventually “inflate away” our debt, but that solution wouldn’t work for long. Over one-third of the marketable debt rolls over within a year, and three-fourths within five years; investors, once burned, would likely charge an extra inflation premium at the earliest opportunity.

Many citizens are incensed about today’s high deficits and less concerned about the long-run budget imbalance. That’s the opposite of most experts’ view. Few mainstream economists call for tighter fiscal policy now — while the economy remains fragile — but they overwhelmingly warn that we must avoid a debt explosion in the long run.

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities has called for stabilizing the deficit at about 3 percent of GDP — and the debt held by the public at or modestly above 70 percent of GDP — within the coming decade.[12] That itself is an ambitious goal: if done in one package, it would require belt-tightening about one-and-a-half to two times as large as the biggest deficit-reduction package ever adopted in the past. Accomplishing that as the baby boomers begin to retire in large numbers — and without the “peace dividend” that permitted reductions in defense spending in the 1990s — will be daunting. It will certainly require a balanced package of both program reductions and tax increases.

There is no question that the long-term fiscal problem is extremely challenging. But it would be a mistake to complicate that challenge even more by adopting a misplaced focus on the wrong target. The deficit commission, which has the potential to educate policymakers and the public about our fiscal challenge and the need to begin putting measures into effect to deal with it after the economy recovers, should not add to confusion by adopting a fiscal target that does not make sound economic sense.

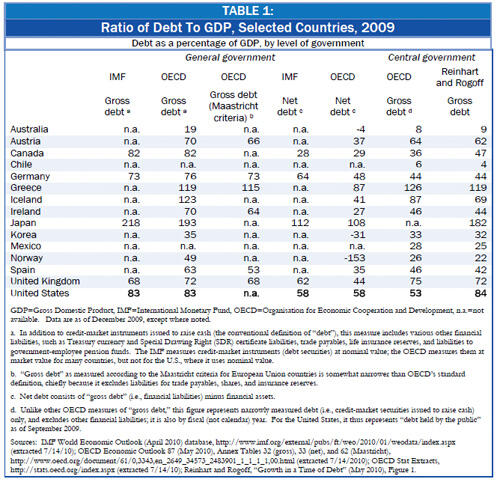

The IMF and the OECD, which collect and publish statistics on various countries’ finances, have developed standard concepts to facilitate international comparisons. In the area of government debt, three distinctions are key:

- Central or general? Most IMF and OECD statistics focus on general government debt — that is, debt owed by all levels of government in a country. In the U.S. context, general government means federal, state, and local. More narrowly, what the IMF and OECD call central government means (in the U.S. context) federal. Reinhart and Rogoff focus on central, not general, government debt.

- Debt or liabilities? Often, what the IMF and OECD call debt actually represents a broader category of financial liabilities. Such figures include credit-market instruments (like U.S. Treasury securities) issued to raise cash, which is the conventional definition of “debt,” plus various other financial liabilities of government (see footnote “a” in Table 1).

- Gross or net debt? Governments incur financial liabilities, but they also own financial assets: gold, foreign exchange, currency and checkable deposits, student loans and other loans, accounts receivable, and other assets. Net debt (or more accurately, net liabilities) consists of gross debt (or liabilities) minus those assets (based on the assets’ actual worth).

Careful readers, therefore, should not become confused when they see seemingly contradictory figures from the IMF and the OECD. Table 1 shows the latest OECD data for general and central government gross debt, and compares the latter to Reinhart and Rogoff’s figures (see the two rightmost columns). As the table makes clear, Reinhart and Rogoff’s estimates generally resemble the standard measure, with the glaring exceptions of the United States and Canada.