Claims that states will bear a significant share of the costs of the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) Medicaid expansion — and that this will place a heavy financial burden on states — do not hold up under scrutiny. Congressional Budget Office (CBO) analysis indicates that between 2014 and 2022, the ACA’s Medicaid expansion will add just 2.8 percent to what states spend on Medicaid, while providing health coverage to 17 million more low-income adults and children. In addition, the Medicaid expansion will produce savings in state and local government costs for uncompensated care, which will offset at least some of the added state Medicaid costs.

The health reform law requires states to extend Medicaid coverage to non-elderly individuals with incomes up to 133 percent of the poverty line, or about $30,700 for a family of four. The combination of the law’s Medicaid expansion and its subsidies to make coverage affordable for people who aren’t affluent but have incomes too high to qualify for Medicaid will reduce the number of uninsured people by 33 million by 2022, according to CBO.

The health reform law provides a favorable financial deal for states, in several respects.

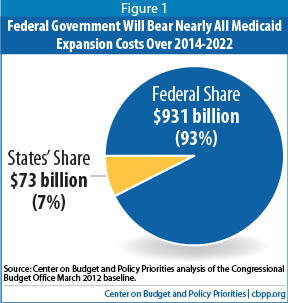

- CBO estimates show that the federal government will bear nearly 93 percent of the costs of the Medicaid expansion over its first nine years.

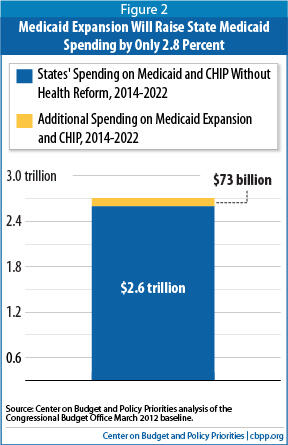

- The additional cost to the states represents a 2.8 percent increase in what states would have spent on Medicaid from 2014 to 2022 in the absence of health reform.

- This 2.8 percent figure overstates the net impact on state budgets because it does not reflect the savings that state and local governments will realize in health-care costs for the uninsured.

In short, the Medicaid expansion will significantly increase coverage at a modest cost to state Medicaid programs, and it will lower state costs for providing care to the uninsured.

Starting on January 1, 2014, the health reform law will expand Medicaid eligibility to 133 percent of the poverty line for all non-elderly citizens and individuals who have lawfully resided in the United States for more than five years, and who are not eligible for Medicare. Millions of low-income parents and people with disabilities, and millions of non-disabled low-income adults who don’t have dependent children, will become eligible for the program. CBO estimates that by 2022, some 17 million more individuals — most of whom are now uninsured — will have insurance through Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP).[1]

Since its inception, Medicaid has been jointly financed by the federal government and the states, with the federal government currently paying 57 percent of the cost, on average. The health reform law takes a different approach. To minimize the financial burden on states of the Medicaid expansion, the federal government will pay nearly 93 percentof the cost of expanding Medicaid over the next nine years.

Specifically, the federal government will assume 100 percent of the Medicaid costs of covering newly eligible individuals for the first three years that the expansion is in effect (2014-2016).[2] Federal support will then phase down slightly over the following several years, and by 2020 (and for all subsequent years), the federal government will pay 90 percent of the costs of covering these individuals. According to CBO, between 2014 and 2022, the federal government will pay $931 billion of the cost of the Medicaid expansion, while states will pay roughly $73 billion, or 7 percent (see Figure 1).[3]

Health reform will likely increase participation among individuals who are currently eligible for Medicaid but are not enrolled. States will receive the regular federal Medicaid matching rate for covering these people — and CBO’s $73 billion estimate of the net increase in state Medicaid costs includes the cost of covering these individuals.[4] The $73 billion equals a 2.8percent increase above the $2.6 trillion that states are projected to spend on Medicaid over the same timeframe in the absence of health reform (see Figure 2).

To assess the fiscal impact on states of the Medicaid expansion, one must look at more than just Medicaid, because the health reform law’s coverage expansions will

reduce some state and local costs. As a result of health reform, Medicaid will essentially pay for many health services now provided to people who are uninsured. Thus, the federal government will bear a substantial share of the cost of providing health care services to people whose health care costs otherwise would be borne in part by state or local governments.

- By sharply reducing the number of people without health insurance, the law will result in a decline in state and local costs for hospital care for the uninsured. In 2008, state and local governments shouldered $10.6 billion, or nearly 20 percent, of the cost of caring for uninsured people in hospitals, according to Urban Institute research.[5]

- By reducing the number of uninsured people, the law also will push down state costs in providing mental health services to the uninsured. State and local governments provided 47 percent of the funding for state mental health agencies, amounting to $14.7 billion, in 2006.[6]

In addition, the health reform law allows states to extend Medicaid coverage immediately, at the state’s regular Medicaid matching rate, to low-income childless adults whom the law requires state Medicaid programs to cover starting in 2014. States that already cover childless adults through state-funded programs — such as Minnesota, Connecticut, and the District of Columbia — have begun shifting coverage of this population to Medicaid.

In other words, a portion of CBO’s estimated $73 billion in additional state Medicaid spending under the new law will be offset by state savings in other areas, primarily as a result of a reduction in the number of the uninsured. Some of the additional state spending on Medicaid will substitute for existing state spending for other health care costs.

Massachusetts Shows That Expanding Coverage Reduces Other Health Care Costs

Massachusetts’ experience with its health reform efforts offers evidence that expanding coverage under a comprehensive health reform plan can lead to sizeable reductions in state costs for uncompensated care.

Massachusetts enacted legislation in 2006 to provide nearly universal health care coverage. The legislation combined a Medicaid expansion with subsidies to help low- and moderate-income residents purchase insurance, an employer responsibility requirement, and a requirement for individuals to obtain coverage. All of these also are core elements of the Affordable Care Act.

With the expansion of affordable health insurance options and the institution of an individual mandate, spending on uncompensated care decreased significantly in Massachusetts. As part of its health reform effort, the state replaced its Uncompensated Care Pool (also known as “Free Care”) with the Health Safety Net, which provides financial support to public hospitals and community health centers that serve low-income residents who are uninsured or underinsured or who have significant medical needs. In 2008, the first full year of health reform implementation, Health Safety Net payments were $252 million, or 38 percent, less than the previous year’s Uncompensated Care Pool payments.a

This reduction in uncompensated care costs coincided with a decline in the share of residents who are uninsured. Only 2.7 percent of residents were uninsured in 2009, compared to 5.7 percent in 2007.b

a Massachusetts Division of Health Care Finance and Policy, “2009 Annual Report – Health Safety Net,” December 2009.

b Massachusetts Division of Health Care Finance and Policy, “Access to Health Care in Massachusetts: Results from the 2008 and 2009 Massachusetts Health Insurance Survey,” November 2009.

The savings that states realize from this large reduction in the number of the uninsured should grow over time. Experts at the Urban Institute have noted that in the absence of health reform, state uncompensated care costs would increase as employer-sponsored insurance continued to erode and the ranks of the uninsured continued to grow.[7] By shrinking the number of the uninsured and having the federal government pick up the overwhelming bulk of the tab, health reform will ease cost pressures on states for uncompensated hospital care, mental health care, and other health care services. Urban Institute researcher John Holahan has observed that states’ savings from no longer having to finance as much uncompensated care may become large enough to fully offset the increase in state Medicaid costs from the law’s Medicaid expansion.[8]

Health reform also will bring other benefits to states. In addition to millions of uninsured people gaining coverage, the law’s insurance-market reforms should improve access to health insurance for people at all income levels. The expansion of health-care coverage will also help protect residents against preventable illnesses and should result in a healthier workforce.[9]

Some critics of the health-reform law have heavily overstated the cost that various states will face as a result of the law’s Medicaid expansion. They have cited estimates purporting to show very large increases in state Medicaid costs, but those estimates have typically been derived through the use of various highly problematic assumptions, including the following:

- Assumptions of rates of participation by eligible individuals that are inconsistent with decades of experience in means-tested programs. Some estimates assume that 100 percent of the people who will be eligible for Medicaid will sign up for the program. Yet nomeans-tested public program has ever achieved a 100 percent participation rate. Even Medicare, a universal social insurance program, enjoys a participation rate of only 96 percent, and a variety of other means-tested programs have participation rates of 43 percent to 86 percent.a While a mandate to have health insurance, requirements to establish a simplified and seamless enrollment process, and the publicity and outreach efforts surrounding the expansion should result in increased enrollment, the evidence is overwhelming that the participation rate will not be 100 percent.b

- Assumptions concerning “crowd out” rates among people who otherwise would have private insurance that are inconsistent with historical experience and the research in the field. Some estimates adopt unrealistic assumptions that all or a quite substantial share of already-insured individuals who become eligible for Medicaid will drop their existing coverage and enroll in Medicaid instead. Estimates of increased Medicaid costs generated for Mississippi, Nebraska and Indiana have assumed that between 35 and 45 percent of all new Medicaid enrollees in the state will be people who drop private coverage to enroll in Medicaid.c The research indicates, however, that “crowd-out” rates of this magnitude are highly unlikely. Studies that have looked at whether Medicaid crowds out private health insurance, focusing primarily on state expansions of children’s Medicaid eligibility in the 1990s, show that between 10 percent and 20 percent of new Medicaid enrollees previously had private coverage, rather than much higher percentages.d

- Assumptions of costs per newly enrolled Medicaid beneficiary that the data show to be heavily overstated. An estimate of increased state costs in Mississippi concludes that if the ACA’s Medicaid expansion had been in effect in 2009, the cost would have been $4,540 per beneficiary for the adult expansion population and $2,421 per beneficiary for children. Yet estimates that the Urban Institute produced for the Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured find that per-capita costs for the adult and child populations in Mississippi’s Medicaid program were far lower — $2,612 and $1,798, respectively — in 2009,e and the Urban Institute figures are based on actual data that the state reported. Another estimate, cited to show that the Medicaid expansion would place high costs on Nebraska, contended that the per-beneficiary cost of covering parents whom the ACA will make newly eligible for Medicaid would have been $4,881 in that state if the expansion had been in effect in 2009. This figure is 74 percent higher than what the Urban Institute found to be the cost of covering parents in Nebraska’s Medicaid program in 2009.

a Dahlia Remler and Sherry Glied, “What Other Programs Can Teach Us: Increasing Participation in Health Insurance Programs,” American Journal of Public Health, January 2003.

b Sherry Glied, Jacob Hartz, and Genessa Giorgi, “Consider It Done? The Likely Efficacy of Mandates for Health Insurance,” Health Affairs, November/December 2007.

c For a more detailed analysis of these estimates and the studies from which they are drawn, see January Angeles, “Some Recent Reports Overstate the Effect on State Budgets of the Medicaid Expansion in the Health Reform Law,” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, October 21, 2010.

d See, for example, Gestur Davidson, Lynn Blewett, and Kathleen Call, “Public Program Crowd-out of Private Coverage: What Are the Issues,” The Synthesis Project, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, June 2004; Lisa Dubay, “Expansions in Public Insurance and Crowd Out: What the Evidence Says,” Kaiser Family Foundation, October 1999; and Anna Sommers, Steve Zuckerman, Lisa Dubay, and Genevieve Kenney, “Substitution of SCHIP for Private Coverage: Results from a 2002 Evaluation in Ten States,” Health Affairs 26:529-537, March/April 2007.

e The Urban Institute and Kaiser Commission on Medicaid and the Uninsured estimates are based on data from Medicaid Statistical Information System (MSIS) and CMS-64 reports from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), 2010. Data provided were for 2007. Estimates were converted to 2009 dollars using the National Health Expenditure Survey’s estimate of the per capita growth in medical expenditures between 2007 and 2009.

Contrary to claims made by some of the health reform law’s detractors, the law’s Medicaid expansion does not impose substantial financial burdens on states. The additional state Medicaid spending that CBO expects to result from the expansion equals 2.8 percent of what states would have spent on Medicaid in the absence of health reform. Moreover, CBO expects the expansion to result in 17 million more people being covered, which will significantly reduce state costs for uncompensated care and related programs. In short, the federal government will pick up the overwhelming share of the costs of the Medicaid expansion, making it a favorable deal for states.