- Home

- Social Security Does Not Face A Near-Ter...

Social Security Does Not Face a Near-Term “Reckoning”

Alarmists’ Claims Are Unjustified, But Action Is Needed to Restore Long-Term Solvency

In recent weeks, several analysts, journalists, and legislators have sounded an alarm about the effect of the current recession on Social Security's near-term prospects, which has fostered an impression that the program may face serious problems in the next few years. Fortunately, this is not the case.

The recession has affected the system's finances, and the next report of the Social Security Trustees — due in coming weeks — is expected to show some deterioration in the program's financial outlook. But Social Security faces no immediate threat. The program continues to run large surpluses and remains capable of paying scheduled benefits in full for the next three decades or so.

Nevertheless, Congress and the Administration should act, sooner rather than later, to restore Social Security’s long-term solvency. Acting sooner allows changes to be phased in gradually and affords people more time to adjust their financial plans.

The Claims

Is Social Security in immediate trouble? Some commentators say yes or imply that it is:

- Writing on Bloomberg.com, Kevin Hassett of the American Enterprise Institute asserts that "[the Social Security] surplus disappeared, eight years ahead of schedule." [1]

- The Washington Post recently reported that "the trust fund's annual surplus is forecast to all but vanish next year—nearly a decade ahead of schedule." [2]

- In floor debate on the budget, Senator Lindsay Graham stated that "[t]he projections for next year are to have a $3 billion [Social Security] surplus, so the day of reckoning….is upon us even quicker than we thought." [3]

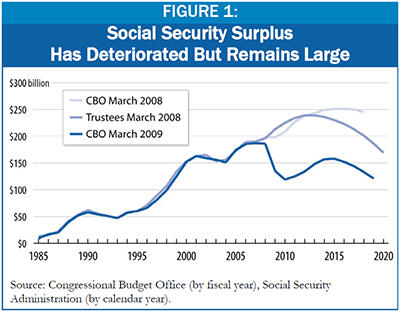

All of these statements cite the latest Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projections.[4] In fact, CBO’s projections do not support these claims and show them to be wide of the mark (see Figure 1).

The Reality

Social Security continues to run significant surpluses, even though the recession has temporarily shrunk their size.

- In 2008, the combined Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (OASDI) trust funds — commonly known as the Social Security trust funds — ran a surplus of $186 billion.

- CBO expects that figure to slip to $135 billion in 2009 and $119 billion in 2010 before rising again.

Not surprisingly, those projections are gloomier than those produced a year or so ago. Recessions take a toll on the entire federal budget, and Social Security is no exception. Payroll taxes are very sensitive to macroeconomic conditions in the short run, while Social Security benefits are less so. According to the National Bureau of Economic Research, the nation suffered recessions in July 1990 through March 1991 and in March through November 2001, and the Social Security surplus slumped in those periods as well. Many economists expect the recession that began in December 2007 to be the deepest since the Depression. It's not surprising that it has caused the Social Security outlook to deteriorate more than in previous recessions, but it has not erased the Social Security surplus or endangered current benefits.

Why then do some commentators say the surplus has vanished? Because they have applied a narrow measure— a comparison of annual Social Security expenditures with annual Social Security revenues excluding the interest payments the trust funds earn. This measure misses an important part of the Social Security trust funds’ income.

Since the mid-1980s, the Social Security trust funds have steadily collected more in payroll taxes and other income than they have needed to pay benefits and administrative costs. They have used that excess to purchase Treasury bonds — almost $2.4 trillion worth by the end of fiscal 2008, bearing an average interest rate of almost 5 percent. CBO expects the funds to earn $119 billion in interest income in 2009.

Excluding interest, the OASDI surplus is indeed expected to slip to a slender $3 billion in 2010 before rebounding as the economy recovers. (See Table 1). That matters to the Treasury; when Social Security generates less extra cash, the government has to tap the credit markets to borrow more (just as the Treasury must borrow more when income tax receipts sag in a recession). Economic recovery will bolster the program's finances, although the annual Social Security surplus will deteriorate again after 2015, as demographic pressures accelerate with the retirement of the baby boomers.

| Table 1: | ||||||||||||

|

| 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

| Income excluding interest | 689 | 684 | 704 | 734 | 769 | 813 | 854 | 889 | 924 | 962 | 1,001 | 1,042 |

| Interest | 114 | 119 | 116 | 116 | 118 | 123 | 130 | 138 | 147 | 155 | 163 | 171 |

| Total income | 803 | 804 | 819 | 850 | 887 | 936 | 984 | 1,028 | 1,071 | 1,117 | 1,164 | 1,213 |

| Expenditures | 617 | 669 | 701 | 725 | 754 | 788 | 827 | 870 | 919 | 973 | 1,031 | 1,092 |

| Surplus | 186 | 135 | 119 | 125 | 134 | 148 | 157 | 158 | 152 | 144 | 133 | 121 |

| Surplus excluding interest | 72 | 16 | 3 | 9 | 16 | 26 | 27 | 20 | 6 | -11 | -29 | -50 |

| Holdings of Treasury securities | 2,366 | 2,502 | 2,620 | 2,745 | 2,879 | 3,027 | 3,184 | 3,342 | 3,494 | 3,638 | 3,772 | 3,892 |

| Source: Congressional Budget Office, March 2009 baseline projections. | ||||||||||||

But from the standpoint of Social Security itself, the trust funds will continue to grow larger and accumulate more assets as long as there is a surplus from the program’s tax revenues and interest earnings combined. In short, commentators who focus on Social Security’s cash flow excluding its interest earnings are describing Social Security’s impact on the Treasury’s need to go into private credit markets to cover the deficits in the rest of the budget. This is an important issue. But it is one that has little significance for Social Security’s ability to pay benefits in the years ahead.

What Should We Expect in the Trustees' Report?

The Social Security Board of Trustees will soon release its annual report.[5] The Trustees’ projections extend for 75 years, so that short-term fluctuations (like the current recession) are put in perspective.

Three key dates often receive attention. In last year's report, those were:

- The date when annual Social Security costs begin to exceed the program’s tax income, not counting its interest income. This was expected to occur in 2017.

- The date when Social Security’s annual costs begin to exceed its total income, including interest. At that point, Social Security will continue to pay full benefits, but will do so by drawing on trust fund assets (that is, by redeeming Treasury bonds that the trust funds hold). In last year’s report, the Trustees projected this would occur in 2027.

- The date when the trust funds will be exhausted and the program thus will no longer be able to pay full benefits. Last year’s report projected that this will occur in 2041. After that date, if policymakers take no other action to shore up the program, benefits will have to be trimmed by 22 percent to 25 percent. [6]

Most observers expect the Trustees’ new projections to be gloomier by several years for each of these three measures. It is important to note that neither the first nor the second “key date” has any programmatic significance, although these dates help to illuminate Social Security's effect on the overall budget.

The fact that Social Security can pay full benefits for about another three decades does not mean, however, that policymakers should wait that long to address Social Security. To the contrary, it would be far better to address the challenge sooner rather than later, by carefully crafting a package that spreads sacrifices fairly across generations and income groups and allows those affected ample notice so they can adjust their financial plans accordingly.

End Notes

[1] Kevin A. Hassett, "Recession Bites into Social Security's Surplus," American Enterprise Institute, March 30, 2009, www.aei.org/publications/filter.all,pubID.29622/pub_detail.asp.

[2] Lori Montgomery, "Recession Puts a Major Strain on Social Security Trust Fund," Washington Post, March 31, 2009, p. A4.

[3] Floor statement by Senator Graham, Cong. Rec. S4159 (daily ed. April 1, 2009).

[4] Congressional Budget Office, A Preliminary Analysis of the President's Budget and an Update of CBO's Budget and Economic Outlook, March 2009. Supplemental Data on Spending Projections, Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance Trust Funds, March 2009 Baseline. Available on-line at http://www.cbo.gov/budget/factsheets/2009b/oasdiTrustfund.pdf.

[5] The Trustees of Social Security are the Secretaries of Labor, Treasury, and Health and Human Services; the Commissioner of Social Security; and two outside experts appointed as public trustees. The two public seats are currently vacant.

[6] These dates are for the combined OASI and DI trust funds. In isolation, DI faces these key dates sooner.