The congressional budget resolutions that the House and Senate are considering this week are essentially consistent with the budget blueprint that President Obama submitted to the Congress in February.[1] The President’s budget and the House and Senate plans (which their respective budget committees recommended last week) all recognize the need to address the immediate threats from the steep economic downturn and financial system crisis, to begin to restore fiscal responsibility and bring deficits under control as the country recovers from the recession, and to meet important national needs in areas such as health care, energy and the environment, and education. All three budget plans call for:

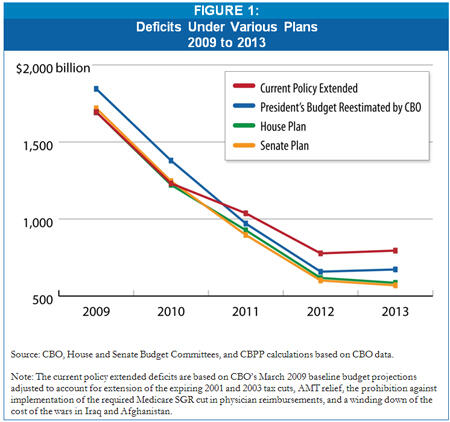

- Deficits that will fall substantially over the next five years, although — fueled by the deep recession, the financial system breakdown, and efforts to address those dual crises — deficits will be high by historical standards. In all three plans, however, deficits over the next five years would be lower than the deficits that would occur if current policies remain unchanged (see Figure 1 below).

- Extension of various expiring tax cuts, particularly those that benefit middle-income taxpayers, without offsetting the costs of the extensions. The three budgets call for Congress to fully pay for any additional tax cuts, and to enact legislation that would close costly and unproductive tax loopholes to help reduce future deficits.

- Enactment of legislation in two key areas, with the requirement that such legislation not add to the deficits in coming years:

- Reforming the nation’s health care system to move toward universal insurance coverage and slow the rate of growth of health care costs system wide, both private and public (which is by far the most important step the nation must take in order to reduce future budget deficits); and

- Overhauling the nation’s energy sector in ways that will increase our energy independence and limit greenhouse gas emissions in order to slow global climate change.

- Modest increases in total funding for domestic discretionary (annually appropriated) programs, which on average have grown very slowly in recent years.

- Enactment of other measures to address national priorities, such as educational and infrastructure improvements.

There are three main areas of difference between the House and Senate budget plans:

- The House plan includes instructions to three committees to report legislation under the reconciliation procedures of the Budget Act. (The plan assumes the reconciliation legislation will address health reform and changes in student financial aid for higher education, but the Budget Act does not allow the budget resolution to dictate the particular policy area to be addressed by the reconciled committees.) The Senate plan, in contrast, does not include any reconciliation instructions. If reconciliation instructions are included in the final budget plan that the House and Senate approve (with both House and Senate committees instructed to report legislation), the Senate could pass the resulting reconciliation legislation with 51 votes instead of 60.[2]

- Both the House and Senate assume that the costs of extending expiring middle-class tax cuts, the current estate tax rules, and relief from the alternative minimum tax (for at least one year in the case of AMT relief) will not have to be paid for. In addition, the House — but not the Senate — provides that under specified circumstances the costs of the extensions will not count for purposes of determining compliance with the pay-as-you-go rule. Under that approach, the House would not have to waive the pay-as-you-go rule for legislation extending those policies unless the legislation also contains other tax cuts that are not fully paid for. Under the Senate approach of not providing any relief from the pay-as-you-go rule, even legislation that only extends the current policies that the plan assumes will not be paid for would require a 60-vote waiver to overcome a pay-as-you-go point-of-order.

- As explained below, the House approach to legislation extending specified current policies that are scheduled to expire under current law — which on the surface may appear less fiscally responsible —offers a significantly better chance of limiting the cost of that legislation given the strong support that exists in Congress for extending the current policies without paying for the extensions and likely efforts to add other tax cuts to the legislation without paying for them.

- Both plans reduce the level of funding for domestic discretionary programs somewhat below the President’s level, but the Senate plan’s reduction is larger. The President’s budget calls for a 3.9 percent increase in total funding for domestic discretionary programs, after accounting for inflation and several unavoidable increases in costs for 2010 — such as for the decennial Census — that are not related to any program expansion. The House plan provides for a 3.5 percent increase, while the Senate plan would allow for a 1.5 percent.

A more detailed analysis of elements of the House and Senate budget plans follows.

The President’s budget and the House and Senate budget plans have deficits in 2009 and 2010 that would be greater as a share of the economy than in any year since World War II. The deficits are this high not because the policies proposed in those plans would increase the deficit relative to what would happen if current policies are left unchanged, but rather because the country is facing the most severe recession since World War II and a severe crisis in its financial system, and also because policies enacted in recent years have increased spending and reduced tax revenues.

If current policies are extended — that is, if the tax cuts enacted in 2001 and 2003 that are scheduled to expire in 2010 are continued, relief from the AMT is extended, Congress continues to prohibit a scheduled 20 percent reduction in Medicare physician reimbursements, and our troops in Iraq and Afghanistan are fully funded as those conflicts are gradually wound down — deficits will total $4.7 trillion in 2010 through 2014. [3] According to the Congressional Budget Office, deficits under the President’s budget would be $269 billion smaller over that period. The House budget plan has deficits that are $747 billion smaller in 2010 through 2014 than under a continuation of current policies, and the Senate plan’s deficits are $878 billion smaller than the current policy extended deficits. (See Figure 1.)

The deficits in the House and Senate plans are lower than under the President’s budget largely because: they assume that Congress will not enact legislation requested by the President that would provide additional funds to deal with problems in the nation’s financial system; they assume lower levels of discretionary spending over the next five years than the President requested; they assume that the cost of two or more years of AMT relief will be paid for; and they assume larger savings from closing tax loopholes than the President’s budget did.

The President’s budget proposes that middle-income tax cuts enacted in 2001 and 2003 — such as the creation of the 10-percent tax bracket and marriage-penalty relief — be made permanent rather than being allowed to expire at the end of 2010, as is scheduled under current law. The budget also proposes that the 2009 parameters of the estate tax — which provide an exemption from the tax for the first $3.5 million of an estate (effectively $7 million for a couple) and a 45 percent top rate on amounts above the exemption level — be permanently extended. [4] Finally, the President’s budget proposes that AMT relief be extended. The budget assumes that the costs of extending these policies will not be offset.

The President’s budget also proposes that a number of other tax cuts — notably a permanent extension of the Making Work Pay Tax Credit and the improvements in the Child Tax Credit and Earned Income Tax Credit enacted for two years in the recently approved American Recovery and Reinvestment Act — be enacted, but that the cost of those tax cuts be paid for. In the case of the Making Work Pay Tax Credit, the President proposes that the extension of the credit be considered as part of a deficit-neutral energy and climate change package, with the cost of the Making Work Pay credit being offset by a portion of new revenues generated from proposed auctions of allowances for emissions of greenhouse gas. The extension of this credit is proposed as part of the climate change package because it would be one element of a plan to offset the effects on lower-, moderate-, and middle-income consumers of the increase in energy and energy-related costs that will occur as greenhouse gas emissions are reduced. [5] The President’s budget also proposes to close a number of tax loopholes — for instance, the provisions of the tax code that allow U.S. companies with overseas subsidiaries to defer taxes on profits earned abroad — to pay for other proposed new tax cuts and to help reduce the deficit.

The President’s budget also assumes that his proposal to increase revenues by limiting the benefit of itemized deductions to no more than 28 percent of the amount of the deduction will be used to help offset the cost of health reform legislation, which the President has said should be deficit neutral.

Both the House and Senate budget resolutions assume that the 2001 and 2003 middle-income tax cuts, the 2009 estate tax parameters, and relief from the AMT will be extended. They both assume that the cost of simple extensions of the middle-class tax cuts and the estate tax parameters will not be paid for. The Senate assumes that the cost of extending AMT relief for three years will not be paid for, while the House assumes the cost of extending it for one year will not be offset.

The House plan not only assumes that the specified expiring tax cuts will be extended without being paid for, but it also includes procedures that will allow legislation implementing the extensions to be considered without the need to waive Budget Act or pay-as-you-go points of order so long as the legislation does not cost more than the estimated cost of extensions. (See the box on the next page for an explanation of those procedures.)

The Senate budget resolution contains no similar provisions to exclude the cost of extending certain current policies from the pay-as-you-go calculations. Like any other legislation affecting mandatory spending or revenues, legislation that extends these expiring tax provisions and does not include offsets for the cost of the extension would be subject to a pay-as-you-go point of order, with 60 votes required to waive the rule and allow the Senate to pass the legislation.

At first glance it might appear that the House provisions that allow legislation extending expiring tax policies to be considered without requiring a waiver of the pay-as-you-go rule when the legislation is considered are less fiscally responsible than the Senate approach, under which any legislation extending a current policy without paying for the cost of the extension has to get a pay-as-you-go waiver. In fact, the House approach offers a much better chance of enforcing fiscal restraint than the Senate approach.

Consider for instance, what is likely to happen when Congress considers legislation to extend the 2009 parameters of the estate tax. There is no doubt that estate tax legislation that extends the 2009 parameters without any offsets to pay for the extension would receive the 60 votes required to waive the pay-as-you-go rule in the Senate. Requiring that legislation to get a waiver would not significantly increase the likelihood that the cost of extending the current estate tax rules will be paid for, but it would increase the chances that the net cost of the legislation would exceed the cost of simply extending the current policies. Various special interests have already been circulating proposals for changes in the 2009 estate tax parameters or other aspects of the estate tax that would substantially increase the legislation’s cost. If any legislation that deals with the estate tax is going to require a waiver and 60 votes in the Senate, then there will be little chance of limiting the cost of that legislation on the Senate floor to the cost of extending the 2009 estate-tax rules. If the 60-vote hurdle must already be surmounted just to extend the 2009 estate-tax parameters, it will be very difficult to hold back efforts to add costly provisions that are not offset, since such measures would not trigger any requirement for 60 votes that didn’t already exist.

By contrast, the House provisions draw a clear line. If the legislation extending the specified current tax policies costs no more than the cost of simply extending those policies, then no pay-as-you-go waiver is required. But if any provisions are added to the legislation that are not paid for, a pay-as-you-go point of order would be triggered and a waiver — which requires 60 votes in the Senate — would be necessary. The House procedure does not guarantee that the Congress will be fiscally responsible in considering legislation extending current policies (no procedure could), but it at least provides an opportunity for fiscally responsible members to try to make a stand at a potentially enforceable line.

The House budget assumes that legislation extending four expiring current policies will be enacted and that the costs of extending the policies will not be offset. The budget plan includes procedures to ensure that, so long as the legislation containing such an extension does not increase the deficit by more than the estimated costs of extending the expiring policy, no Budget Act or pay-as-you-go point of order would constrain consideration of the legislation.*

This outcome is accomplished through a two-step process. First, the plan includes four “Current-Policy Reserve Funds” for legislation extending: (1) an expiring provision blocking scheduled deep cuts in Medicare payments to physicians; (2) expiring middle-class tax relief; (3) relief from the alternative minimum tax; and, (4) current estate and gift tax parameters. Under the terms of the reserve funds, after a committee has reported such legislation, the Chairman of the Budget Committee may adjust the amount of spending allocated to that committee, total revenue and spending levels in the budget resolution, and other amounts in order to insure that no Congressional Budget Act point-of-order limiting the amount a committee can spend or revenues can be cut would apply to the legislation.

Second, legislation that has received a current policy reserve fund adjustment is subject to section 401 of the House resolution. That section provides — subject to a condition described below — that in determining the cost of legislation for purposes of enforcing the pay-as-you-go rule, the Budget Committee Chairman shall not take into account the cost of extending the current policies specified in the reserve fund. This means, for instance, that a pay-as-you-go point of order would not lie against a bill that only extends the middle-class tax cuts — because the cost of the extension for pay-as-you-go purposes would be zero. Nor would a point of order lie against a bill that extends those tax cuts and also includes other tax cuts that are fully paid for. But a bill that extends the middle-class tax cuts and includes other tax cuts that are not paid for would be estimated to increase the deficit and would be subject to a pay-as-you-go point of order.

The other condition that must be met before the Chairman of the Budget Committee can exclude the cost of extending current policies from his calculation of the costs of the bill for purposes of enforcing the pay-as-you-go rule is that the House must previously have passed legislation providing for reinstatement of a statutory pay-as-you-go rule, or that the legislation being considered under the current policy reserve fund provisions must itself provide for statutory pay-as-you-go.

* The congressional pay-as-you-go rule, which is not part of the Congressional Budget Act, prohibits consideration of legislation with provisions that would increase mandatory spending or reduce revenues relative to the current-law baseline unless the costs of those provisions are offset by other spending cuts or tax increases so that the deficit is not increased. A statutory pay-as-you-go procedure was established by the Budget Enforcement Act of 1990, but it expired in 2002.

Like the President’s budget, both the House and Senate budget resolutions assume that a top priority this year is consideration of legislation to implement major reforms of the nation’s health care system that will make progress toward universal health insurance coverage and slow the rate of growth of health care costs system-wide, in both the public and the private sectors. And like the President’s budget, both the House and Senate plans call for the legislation enacting health reforms to be deficit neutral over the 2009-2019 period. (The House requires the legislation to be deficit neutral over the 2009-2014 period as well.)

Both plans include mechanisms — called “reserve funds” — to facilitate consideration of the legislation as long as the legislation does not increase the deficit, but neither plan makes any specific assumptions about the policies that will be included in the health legislation. For instance, unlike the President, who proposed that savings from his proposal to limit the benefit of itemized deductions to no more than 28 percent should be used to offset costs involved in health reform, neither plan makes any specific assumptions about any offsets that will be used to pay for the costs of reform. The mechanism in the budget plan would allow the committees of jurisdiction to make the decisions about the mix of spending and revenues in health reform (both on the cost and offset side) without running afoul of budget rules. (See the box on the next page for an explanation of reserve funds.)

Like the President, the House and Senate Budget Committees understand that slowing the rate of growth of health care costs is the single most important element in bringing the burgeoning deficits projected for coming decades under control. [6] The expected growth of per-beneficiary Medicare and Medicaid costs in excess of the rate of economic growth is by far the largest cause of the projected increase in deficits over the next 50 years. Since Medicare and Medicaid spending per beneficiary has essentially tracked costs per beneficiary system wide for the last 30 years and is expected to continue to do so in the future (unless beneficiaries in those programs are consigned to a second-class level of care), control of future deficits depends on limiting the rate of growth of health costs system wide. This is one reason why the President’s budget and the House and Senate budget plans make health reform, including reforms to begin to bring cost increases under control, a top priority.

Energy and Climate Change Policy

Also like the President’s budget, the House and Senate budget resolutions assume that another priority this year is consideration of legislation making changes in energy policy that will increase energy independence and slow global climate change by limiting greenhouse gas emissions. The House and Senate plans also are consistent with the President’s proposal that such legislation not increase the deficit.

As in the case of health reform, both plans include mechanisms (deficit-neutral reserve funds) to facilitate consideration of the legislation, and neither plan makes any specific assumptions about the policies to be included in such legislation. So, as noted above, neither plan makes a specific assumption about extending the Making Work Pay Tax Credit, which the President has proposed as one of the means of offsetting the effects on consumers of increased energy costs resulting from limits on greenhouse gases. Both plans leave the means of achieving a greater degree of energy independence and limiting greenhouse gas emissions, as well as how to allocate any revenues that may be raised, to the discretion of the committees of jurisdiction. As long as the legislation does not increase the deficit, the deficit-neutral reserve fund guarantees that the legislation will not violate budget rules and face procedural obstacles as a consequence.

Reserve funds are a common method used in congressional budget resolutions to facilitate congressional consideration of legislation assumed by the budget resolution that may involve changes in both spending and revenues. Reserve funds represent an alternative to the resolution making specific assumptions about the amount of increase or decrease in mandatory spending and revenues involved in a particular policy initiative and reflecting those assumptions in the allocation of mandatory spending (the so-called 302(a) allocation) to the committee or committees of jurisdiction and in the aggregate level of spending and revenues assumed in the resolution. With such specific assumptions and no reserve fund, if legislation is reported that increases spending by more than the amount allocated to the committee or reduces revenues by more than the resolution assumed, the legislation would be subject to a Budget Act point of order for exceeding the committee allocation or reducing revenues below the resolution revenue floor even if the net deficit effect of the legislation is no greater than assumed by the budget resolution.

With a reserve fund, the budget resolution can set conditions on the net deficit effect of legislation dealing with a specified policy change (for instance, a reserve fund could apply to “legislation to increase energy independence that increases the deficit by no more than [a specified dollar amount] in fiscal years 2009 through 2014”) without making specific assumptions about the changes in spending and revenues that will result from the legislation. Under the reserve fund, if a committee reports legislation that complies with the reserve fund conditions, the Chairman of the Budget Committee adjusts the committee’s allocation and the budget resolution aggregates to reflect the changes made in the legislation, which ensures that the legislation will not be subject to a Budget Act point of order. The reserve fund approach thus provides flexibility to the committee(s) of jurisdiction to determine exactly the mix of spending and revenues (and spending and revenue offsets) that are appropriate to achieve a desired policy change while ensuring that the legislation does not have a greater effect on the deficit than the resolution assumed.

A particular version of a reserve fund — one that requires that the specified legislation not increase the deficit — is particularly useful now, when a congressional pay-as-you-go rule requiring legislation affecting mandatory spending or revenues to be deficit neutral is in effect. Such a “deficit-neutral reserve fund” ensures that the legislation covered by the reserve fund will not be subject to any other budget point of order for exceeding its allocation or reducing revenues below the floor assumed in the budget resolution if the legislation complies with the pay-as-you-go rule. This allows committees discretion about how much of an increase in spending will be paid for by cuts in other spending and how much will be paid for by increases in revenues (or how much of a tax cut will be paid for by increases in other revenues and how much by cuts in spending) so long as the legislation does not increase the deficit. The House plan includes 13 such deficit-neutral reserve funds and the Senate plan includes 11 deficit-neutral reserve funds.

The House and Senate plans assume exactly the same level of discretionary (annually appropriated) funding for defense as the President’s budget proposes for each year from 2010 through 2014 ($556.1 billion in 2010, not including $130 billion in funding for Iraq and Afghanistan). But both plans assume somewhat lower levels of funding for other — nondefense — programs than the President proposed.

The President has proposed funding totaling $539.7 billion for nondefense discretionary programs for fiscal year 2010. [7] The House plan would reduce that funding by about $7.1 billion, to $532.6 billion. The Senate plan assumes $524.8 billion in funding for nondefense programs, nearly $15 billion less than the President requested.

The President’s budget proposed a significant increase in appropriations for international programs in 2010. (While details of the budget request are not yet available, Administration officials have noted that this request includes a substantial boost in funding for U.S. efforts to fight the ravages of malaria and AIDS in less-developed countries — efforts the President believes will save and improve millions of lives and contribute greatly to improving the image of the United States. around the world.) The House and Senate plans assume that a significant portion of the reduction in funding for nondefense programs (relative to the President’s budget request) will come out of the increase the President proposed for international programs. While the budget resolutions cannot determine how the total pot of discretionary funding will be allocated among appropriation subcommittees, much less among individual programs, it is useful to consider how domestic discretionary programs — all programs other than defense and international — would fare under the assumptions of the House and Senate budget plans.

The House plan assumes that $484.1 billion will be available for domestic programs in 2010, while the Senate plan assumes $475.0 will be available. (The President proposed $485.9 billion for domestic programs.) The amount assumed by the House represents a 5.0 percent increase above the level that CBO projects will be necessary to maintain funding at the 2009 level, adjusted for inflation. The Senate amount represents a 3.0 percent increase in real (inflation-adjusted) terms.

These increases are not accurate depictions, however, of the actual increases in resources available for domestic programs because they do not take into account significant increases in the funding required for two programs in 2010 that have nothing to do with expansions of those programs. First, CBO’s baseline projections for 2010 do not take into account the need for a $3 billion to $4 billion increase in funding for the Census Bureau in 2010 compared to what was appropriated for 2009. [8] That increase is required because of the constitutional requirement to take a census in 2010, which requires the Census Bureau to hire thousands of additional temporary workers to collect census data. Second, the President’s budget includes an additional $3 billion to $4 billion to reflect an estimated increase in the cost of Federal Housing Administration mortgage loan guarantees. Until the last few years, the provisions in appropriation bills setting the volume of loan guarantees allowed were “scored” as producing savings. (As recently as 2003, the savings — or net negative subsidy — for the FHA’s Mutual Mortgage Insurance program was an estimated $1.5 billion.) That was because the rate of defaults on the guaranteed loans was low, and the premiums and fees collected on the loan guarantees more than offset the estimated future cost of dealing with any defaults.[9] In the last few years, however, the turmoil in the housing market has led to an increased rate of defaults. While recent budgets have recognized the increased cost of defaults for outstanding loan guarantees, which show up on the mandatory side of the budget, those budgets continued to assume there would be relatively few defaults on new loans and hence that the cost of new loan guarantees — which shows up on the discretionary side of the budget — would remain quite small. President Obama’s budget, in contrast, assumes a $3 billion to $4 billion increase in the cost of the loan guarantees, relative to the discretionary costs attributed to the program in 2009. This additional cost simply reflects the increased risk of defaults in the program, not any change in the program or any program expansion.

When both the temporary increase in funding for the census and the temporary increase in the costs of FHA mortgage loan guarantees are taken into account, the overall increase in funding that the President’s budget and the House and Senate budget resolutions provide for domestic discretionary programs is modest. [10] Excluding the increases attributable to the Census Bureau and the higher FHA costs and adjusting for inflation, the President’s budget calls for an increase in funding for domestic programs of 3.9 percent. [11] On the same basis, the House plan would increase such funding by 3.5 percent, while the increase under the Senate plan would be 1.5 percent. (See Table 1 on the next page.)

These modest increases come after five years of even more modest increases in funding for domestic programs other than homeland security. [12] Even after taking into account the increase in funding provided in the omnibus appropriation bill for fiscal year 2009, funding for domestic programs other than homeland security grew at an inflation-adjusted average annual rate of only 1.1 percent between 2004 and 2009. It is also important to remember that most programs grew more slowly than that — or actually shrank in real terms — because much bigger-than-average percentage increases in funding were needed to meet significantly increased needs in areas like veterans’ health care, where the return of wounded veterans from Iraq and Afghanistan and the high rate of medical care inflation has made big increases in funding necessary.

Finally, the argument made by some that funding for domestic programs in 2010 can be cut below the levels that the President and the House and Senate plans have recommended without doing any

harm because the economic recovery legislation provided a significant amount of funding for domestic discretionary programs is misguided. It ignores the fact that the reason for enacting the recovery package was to increase federal, state, and consumer spending in order to limit the steep drop in private consumption that has led many businesses to lay off employees and curtail their investments (because the firms cannot sell all of the goods and services they have been producing). Cutting funding for the regular 2010 appropriation bills below the levels that the President’s budget and the House and Senate budget plans call for would undercut the economic stimulus the recovery act will provide by partly counteracting the increase in demand for goods and services that the recovery legislation is designed to produce.

| TABLE 1:

Fiscal Year 2010 Discretionary Budget Authority

(dollars in billions) |

| | CBO Baseline | President's Budget* | House Plan | Senate Plan |

| Nondefense | $499.9 | $539.7 | $532.6 | $524.8 |

| % Increase over baseline | n/a | 8.0% | 6.5% | 5.0% |

| Domestic | $461.2 | $485.9 | $484.1 | $475.0 |

| % Increase over baseline | n/a | 5.4% | 5.0% | 3.0% |

Domestic without Commerce

and Housing Credit | $455.0 | $472.7 | $470.9 | $461.7 |

| % Increase over baseline | n/a | 3.9% | 3.5% | 1.5% |

| * Adjusted for consistency with congressional treatment of highway obligation limits and Pell Grant funding. Source: CBO, House and Senate Budget Committees, CBPP calculations based on CBO and Administration data. |

In addition to the policies discussed above, the budget resolution assumes that Congress will address important issues ranging from improvements in child nutrition and the Low-Income Home Energy Assistance Program to defense contracting reforms . Given the commitment of both the House and Senate plans to paying for any new tax cuts or mandatory program expansions (beyond extension of specified policies that are currently in effect but are scheduled to expire), the plans deal with the need to address these issues through the deficit-neutral reserve fund approach applied to health care reform and energy and climate change legislation. As described in the box on page 8, these funds allow the committees with jurisdiction over legislation in the specified areas to determine the exact nature of the policy changes to be made and ensure that no budget rules will constrain consideration of the proposed legislation so long as the legislation does not increase the deficit.