BEYOND THE NUMBERS

As we’ve explained, the House Republican budget would seriously weaken Medicaid by repealing health reform’s Medicaid expansion and, on top of that, converting it to a block grant and cutting it another $1 trillion over ten years. The House budget also requires “able-bodied adults” otherwise eligible for Medicaid to demonstrate that they’re working, searching for work, or in an education or training program in order to qualify for Medicaid coverage.

A work requirement in Medicaid would be ill-advised. It would conflict with Medicaid’s basic purpose of providing health care to people who cannot otherwise afford it and very likely increase the number of uninsured.

Before health reform enabled states to expand Medicaid to cover all low-income adults up to 138 percent of the poverty line, most Medicaid beneficiaries were children, seniors, people with disabilities, or very low-income parents. Before health reform, only parents with incomes below 61 percent of the poverty line were eligible for Medicaid in the typical state. This eligibility threshold would likely fall even lower under the House budget, because its $1 trillion in cuts in federal funding for state Medicaid programs (on top of repealing the Medicaid expansion) would likely lead many states to restrict Medicaid coverage to a still greater degree than prior to health reform.

A work requirement could leave many of the very poor parents who remained eligible without health insurance. The concept of a work requirement in Medicaid may sound attractive, but it could result in people with various barriers to employment — primary caregivers for family members, people with mental health or substance use disorders, those who have difficulty coping with basic tasks or have very limited education or skills, and people without access to child care or transportation — without health coverage.

Consider what’s happened in cash assistance programs for poor families with children. Before the changes in these programs of the mid-1990s, for every 100 poor families with children, about 68 received cash assistance. Today, by contrast, for every 100 poor families with children, only 23 receive this assistance. Rigid work requirements that are often ill-suited for very poor parents with various problems are one reason why.

Some view the sharp drop in the share of poor families receiving cash assistance as a positive development. (We disagree.) But everyone should agree that having very poor parents lose health insurance would be highly undesirable. It would conflict with Medicaid’s core mission of ensuring access to health care for low-income families.

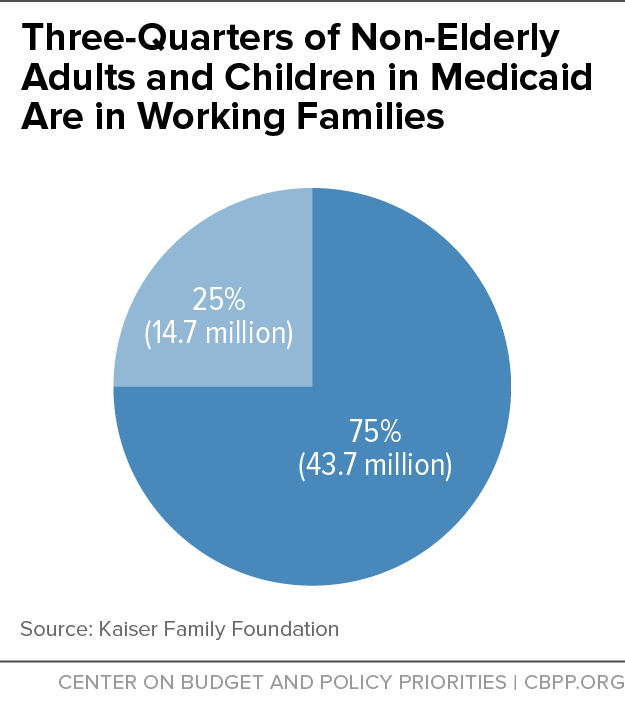

Moreover, most people covered by or eligible for Medicaid who can work do work. Three-quarters of non-elderly adults and children enrolled in Medicaid live in a family with at least one part-time or full-time worker (see chart).

Those who aren’t working often have a specific reason. A Kaiser Family Foundation study found that among uninsured adults likely to gain Medicaid coverage (if their state adopted the Medicaid expansion) who are unemployed, 29 percent weren’t working because they were caring for a family member, 20 percent were looking for work, 18 percent were in school, 17 percent were ill or disabled, and 10 percent were retired.

A work requirement on low-income people for Medicaid won’t lift these individuals out of poverty. In fact, it may reduce their ability to work steadily by putting health coverage out of reach and thereby causing them to have more (or more serious) health problems. Rather than creating new barriers to health care, policymakers should consider policies that give low-income individuals and families better chances of succeeding in the labor market by strengthening education, training, and employment programs while assuring they have access to health care.