off the charts

POLICY INSIGHT

BEYOND THE NUMBERS

BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Lawmakers in Minnesota and New Hampshire are considering amending their constitutions to require a supermajority (three-fifths) vote to approve tax increases, rather than the simple majority required for all other legislation.

Image

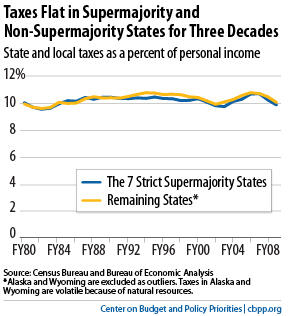

While proponents claim that the change will lead to lower taxes, our new analysis finds that the few states with strict supermajority requirements levy taxes at virtually the same rate as other states, on average (see chart). That’s because most states — with or without a supermajority requirement — generally avoid tax increases large enough to cause taxes to grow as a share of personal income.

Supermajority rules also can make it much harder for a state to manage its finances properly, for these six reasons:

- They protect special interest tax breaks. Supermajority requirements make it even harder for states to kill ineffective and unfair tax breaks than it already is, since repealing them often counts as a tax increase. This means that costly deductions, credits, and other tax expenditures that often benefit only a handful of corporations or individuals have more protection than special interest spending, which lawmakers can cut by simple majority vote.

- They shift costs from some residents to others. If raising taxes and repealing tax breaks requires a supermajority vote, lawmakers looking to raise revenue will more likely raise fees, tuition, and other levies not subject to a supermajority requirement. This shifts the cost of government from some taxpayers to others — like, for instance, students and Medicaid recipients.

- By raising interest rates, they may actually raise state spending and dissuade states from making capital investments. Research shows that investors are less willing to buy bonds from states with supermajority tax requirements because such rules reduce states’ flexibility to raise revenue, making them potentially less trustworthy borrowers. Supermajority states thus are more likely to have lower bond ratings, which forces them to make higher interest payments and pushes up the cost of bond-financed projects like roads and public buildings.

- They make it harder to finance transportation investments. States finance most highway and other transportation projects with gas taxes that are not indexed for inflation. To keep up with rising highway-construction costs, states must periodically raise gas tax rates, but supermajority rules make that more difficult. Five of the seven strict supermajority states have not raised gas taxes in over 15 years, while most other states have increased them at least once in the last decade.

- They limit lawmakers’ budget options during downturns and can make downturns deeper and longer. By making it harder to raise taxes, supermajority rules encourage states to rely on a cuts-only response to recession-induced budget gaps. That’s a particularly poor choice for states in such circumstances: severe spending cuts remove demand from the economy, further slowing an already weak economy. Raising taxes, particularly from wealthy people and multi-state corporations, is a less damaging approach during recessions because it generally has a smaller impact on overall demand. That’s why states’ best approach is often a balanced one that includes revenue increases as well as targeted spending cuts.

- They strengthen special interests and ideological extremists. In supermajority states, a minority of legislators and special interest lobbyists can hold the majority hostage until their demands are met. For example, a bipartisan commission found that California’s (now-repealed) supermajority requirement to pass budgets forced the enactment of substantial “pork-barrel” legislation that individual legislators had promoted.

Topics:

Stay up to date

Receive the latest news and reports from the Center