BEYOND THE NUMBERS

No one knows how tomorrow’s October jobs report will affect Federal Reserve policymakers’ views about whether to start raising interest rates in December. But here are some things to consider in assessing whether the job market is making the “continued progress toward maximum employment” that the Fed wants to see.

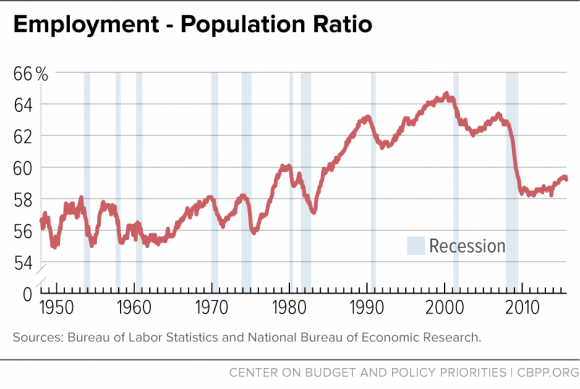

Share of the population with a job. Although unemployment has fallen from 10 percent in October 2009 to just over 5 percent, that hasn’t brought a commensurate recovery in the share of the population with a job (see the chart below from this chart book). Rather than moving from unemployment to a job, many people dropped out of the labor force altogether because they thought it would be fruitless to look for a job when so few seemed to be available. Others never joined the labor force in the first place. (To be counted as unemployed, a person has to be actively looking for work.)

With a growing retirement-age population, the employment-to-population ratio even in a healthy economy will be lower than it was a decade ago, but there are still people who want to work who can be enticed back into the labor force if they think they’ll find work. In tomorrow’s report, a drop in unemployment accompanied by a rise in labor force participation would be an encouraging sign of further labor market progress.

Job creation. Payroll employment growth has slowed from an average gain of 213,000 jobs a month in the first half of this year to an average of 167,000 in the last three months, including two straight months of under 150,000. Slowing population growth over the past decade or so has reduced the threshold monthly job growth needed to raise the employment-to-population ratio from about 150,000 to under 100,000. The faster the rate of job creation, the quicker the drop in unemployment and the rise in labor force participation — but job growth of 150,000 still represents progress toward maximum employment.

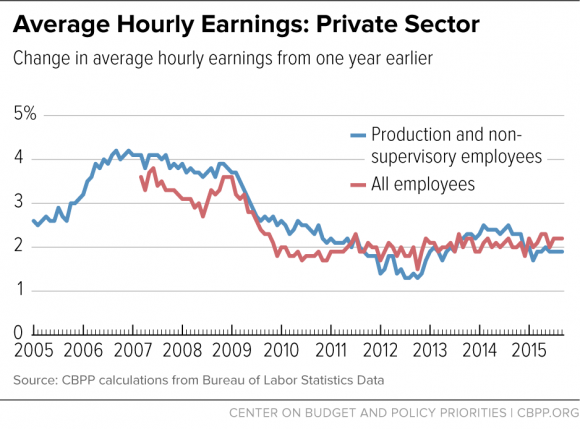

Wages. One important indicator that labor markets are tightening and the economy is approaching maximum employment is still missing in action — rising wages. Average hourly earnings (before adjusting for inflation) of employees on private payrolls have been growing modestly throughout the recovery, averaging about 2 percent annually (see chart).

Inflation is currently running very low due to low energy prices, temporarily stretching the purchasing power of workers’ paychecks. Since the start of the recovery in mid-2009, however, price inflation has averaged about 1.8 percent a year and therefore real (inflation-adjusted) wages have hardly grown at all. Average hourly earnings in October of $25.13 for all employees and $21.12 for production and non-supervisory employees would continue the trend of 2.2 percent growth in the former and 1.9 percent in the latter — rates well below what they would be in an economy at maximum employment.

We continue to conclude that there’s more to be done to achieve the Fed’s goal of maximum employment. Further progress requires solid enough job creation to put more unemployed workers back to work and bring more people back into the labor force. The Fed should be wary of slowing that progress prematurely.