BEYOND THE NUMBERS

With Social Security a likely topic in the 2016 presidential campaign, our analysis of this year’s Social Security trustees’ report shows that Social Security doesn’t face a crisis — it has the resources to pay full benefits for nearly two decades even without any changes. But it faces a long-term funding shortfall that policymakers should address reasonably soon so the program can fully meet its promises.

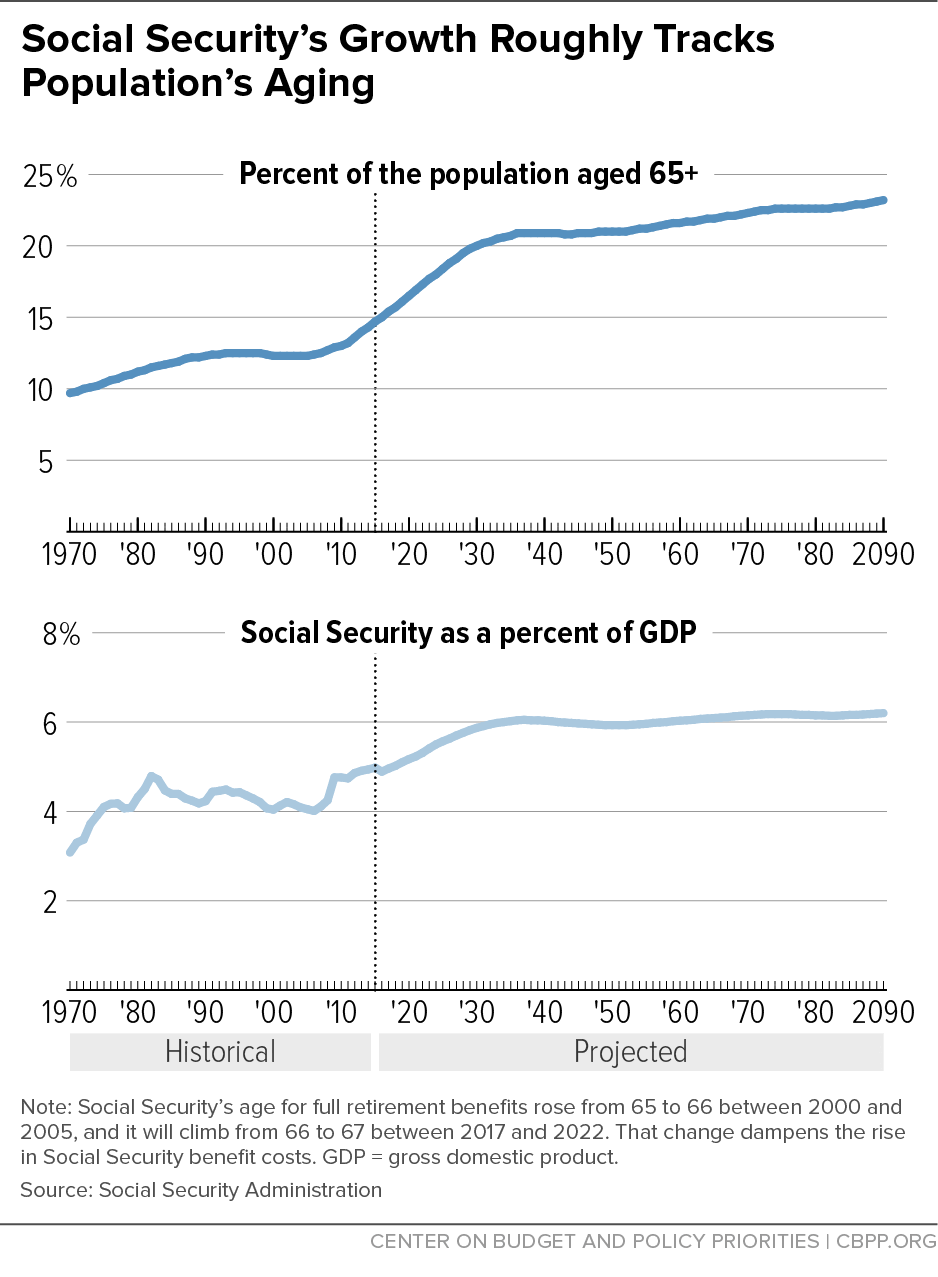

Social Security costs will rise gradually over the next few decades, from about 5 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) today to slightly over 6 percent in the 2030s and beyond. That growth roughly tracks the aging of the population (see figure), though scheduled increases in the age for full retirement benefits dampen the rise in costs.

Because Social Security’s revenues don’t quite keep up with its costs, the trustees expect that the combined Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and Disability Insurance trust funds will be exhausted in 2034. That’s a year later than they projected last year.

Even after 2034, Social Security could still pay three-quarters of scheduled benefits from its incoming tax revenues. The program isn’t bankrupt, and alarmists who say it won’t be around when today’s young workers retire misrepresent the projections.

We focus here on the combined trust funds. Policymakers need to reapportion taxes between the retirement and disability funds by late 2016 — a step that they’ve taken before, in both directions, whenever necessary — to avoid depletion of the disability fund.

Social Security’s 75-year shortfall is 1 percent of GDP. Critics who like to cite scary dollar figures — like an “unfunded liability” of $10.7 trillion over 75 years — almost never bother to mention the economy’s size, which is crucial to the program’s affordability. GDP over the next 75 years will total nearly $1,200 trillion, and the shortfall is just 1 percent of that.

In short, Social Security faces a funding gap that’s well-documented but manageable. Because benefits are so modest and are the main source of income for most beneficiaries, revenues — not benefit cuts — should make up most of a solvency package. See the full paper for some options that lawmakers should consider.