BEYOND THE NUMBERS

House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Dave Camp has said he will unveil tax reform legislation by the end of this year that he aims to be “revenue-neutral.” But, a revenue-neutral package would be inadequate because tax reform should generate revenue to help cut long-term deficits. Further, appearances of “revenue neutrality” can be deceptive, if policymakers use timing gimmicks to generate illusory savings.

Such gimmicks would appear to pay for permanent rate reductions and other tax cuts during the first decade but would lead to higher deficits later. Timing gimmicks shouldn’t be a part of responsible individual tax reform proposals. (There are similar risks in corporate tax reform, as we’ve previously explained.)

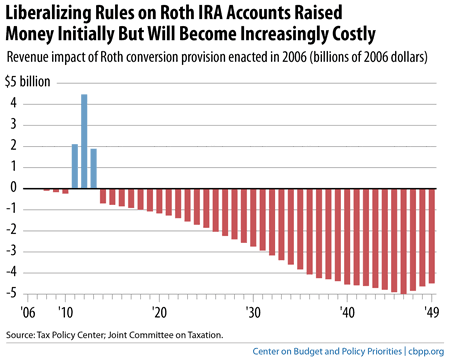

One of the worst gimmicks, we explain in our new paper, is treating as tax increases changes that raise revenues initially but lose as much or more revenues later. For example, President Bush and Congress in 2006 liberalized the rules regarding Roth retirement saving accounts. The provision raised $6.4 billion in the initial decade, but it expanded deficits by over $12 billion in the second decade, and by another $30 billion in the decade after that (see chart). Congress used the revenue that this gimmick produced over the first ten years to pretend to partially “pay for” other deficit-increasing tax cuts in the 2006 legislation, such as an extension of dividend and capital gains tax cuts.

Another gimmick ignores the fact that the revenue gains from some tax changes shrink over time. The fact that the savings from a given set of tax changes may diminish over time doesn’t mean the changes aren’t worth doing. Policymakers should limit or eliminate inefficient tax expenditures where possible. But, they shouldn’t pretend that the temporary portion of the revenues raised will continue and use those temporary savings to meet deficit reduction goals or to “pay for” costly permanent rate cuts.

Such gimmickry isn’t inevitable: policymakers carefully crafted health reform so that it would reduce the deficit in the second ten years as well as the first ten, and they sought estimates from the Congressional Budget Office on the long-run impact of proposed immigration reform.

Policymakers should follow those examples again now and reject tax reform that uses short-term gimmicks that worsen long-run fiscal challenges.

Click here to read the full paper.