BEYOND THE NUMBERS

Lawmakers are seriously considering cutting or even repealing the personal income tax in at least ten states: Indiana, Kansas, Louisiana, Missouri, Nebraska, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, and Wisconsin. One of the most common arguments for these tax cuts is that they’d encourage small businesses to grow and create jobs, since most small firms pay taxes on their profits under the personal income tax.

In reality, personal income tax cuts would likely be counterproductive, as my new paper explains. They are a very poor way to stimulate job creation among small businesses, and, by weakening state revenues, they impair states’ ability to provide the educated workforce, well-maintained roads and bridges, and adequate police and fire protection that businesses demand.

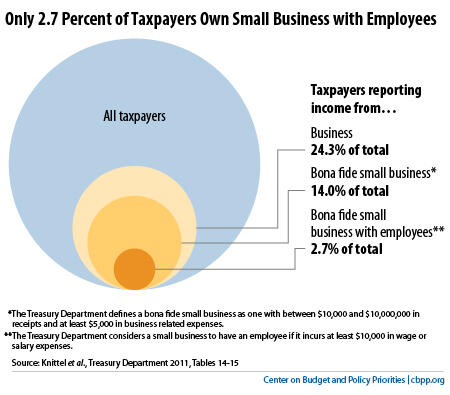

- The vast majority of those who would get a personal income tax cut are in no position to create small-business jobs. As the graph shows, only 2.7 percent of personal income taxpayers own a bona fide small business with any employees other than the owner or owners, according to a Treasury Department study. Most high-income households — the group that likely would get the most money back from a personal income tax cut — are not small business owners.

- Most small businesses make too little money for tax cuts to produce enough income to pay new employees. Nearly nine in ten small businesses have less than $50,000 in taxable income in a given year. State income taxes for these businesses already are so low — just a few thousand dollars in most cases — that even eliminating the tax wouldn’t come close to paying one full-time worker’s salary.

- Most small business owners aren’t significant “job creators.” Even among the small fraction of taxpayers who are true small business owners, most wouldn’t create jobs in response to a state income tax cut. For example, many small business owners — such as lawyers, accountants, and real estate agents — don’t need other employees other than perhaps an office administrator. Many others are passive investors who don’t have the authority to hire additional workers.

- Small businesses hire employees based on product demand, not tax levels. As the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office has observed with respect to federal tax cuts for businesses: “[I]ncreasing the after-tax income of businesses typically does not create much incentive for them to hire more workers in order to produce more, because production depends principally on their ability to sell their products.” Also, employee wages are fully deductible from state income taxes, so the presence of taxes is not likely to discourage hiring.

- Studies show that state personal income taxes have almost no relationship to small business growth. For example, a careful empirical study commissioned by the U.S. Small Business Administration found “no evidence of an economically significant effect of state tax [policy] portfolios on entrepreneurial activity.”

- State income tax cuts risk eroding public services that are important to small businesses. States have to balance their budgets, so when they cut taxes, the money has to come from someplace. That “someplace” will likely be state support in areas crucial to businesses, particularly K-12 and higher education. A recent National Governors Association report points out that “states that have a higher average level of education tend to have greater levels of economic success.”

In short, cutting state income taxes in the name of boosting small business job creation and entrepreneurship represents a quintessential violation of the “first, do no harm” principle.