BEYOND THE NUMBERS

As we’ve explained, timing gimmicks pose a threat to fiscally responsible corporate tax reform. A recent comment by Dr. Laura Tyson, a University of California, Berkeley professor and an adviser to a coalition of American businesses that favor comprehensive corporate tax reform, illustrates the point. Testifying before the Senate Finance Committee, she responded to a question by noting that one possible use of one-time revenues from a tax on multinationals’ current stock of overseas profits could be to “pay for” a permanent cut in corporate tax rates. That’s a way for corporate tax reform to increase the deficit over the long term.

Multinationals have about $2 trillion in profits stashed offshore to avoid U.S. tax; they don’t owe tax on them until they declare them “repatriated” to the United States. Any enacted corporate tax reform will likely include a mandatory, one-time transition tax on those existing foreign profits to wipe the slate of those deferred tax liabilities. (Future overseas profits would be treated differently.)

Such a transition tax could raise significant revenues. The President’s proposed transition tax of 14 percent, for example, would raise $268 billion over 2016-2025. Companies would have six years to pay the tax, but since the tax wouldn’t apply to future overseas profits, it wouldn’t raise any revenues after the sixth year.

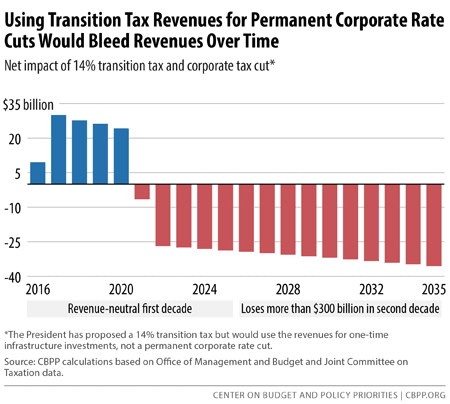

That’s the problem with suggestions that revenues from a transition tax could be used to help “finance” a lower corporate rate. In reality, those one-off revenues can’t pay for any permanent tax cuts because the revenues disappear after six years. The result would be a reform package that’s revenue neutral within the ten-year budget window but expands deficits by large and growing amounts in future decades.

Indeed, if the $268 billion from the President’s transition tax went to finance a corporate rate cut so that the combined policy would be revenue-neutral in the first decade, such a policy combination would add more than $300 billion to deficits in the second decade (see graph).

To avoid a long-run increase in deficits, the President’s budget devotes the one-time revenues from the transition tax to one-time infrastructure investments.

At a time when critical investments face continued cuts in the name of deficit reduction, it would be inequitable for the corporate sector not only to avoid contributing to deficit reduction but to receive permanent, deficit-increasing tax cuts.